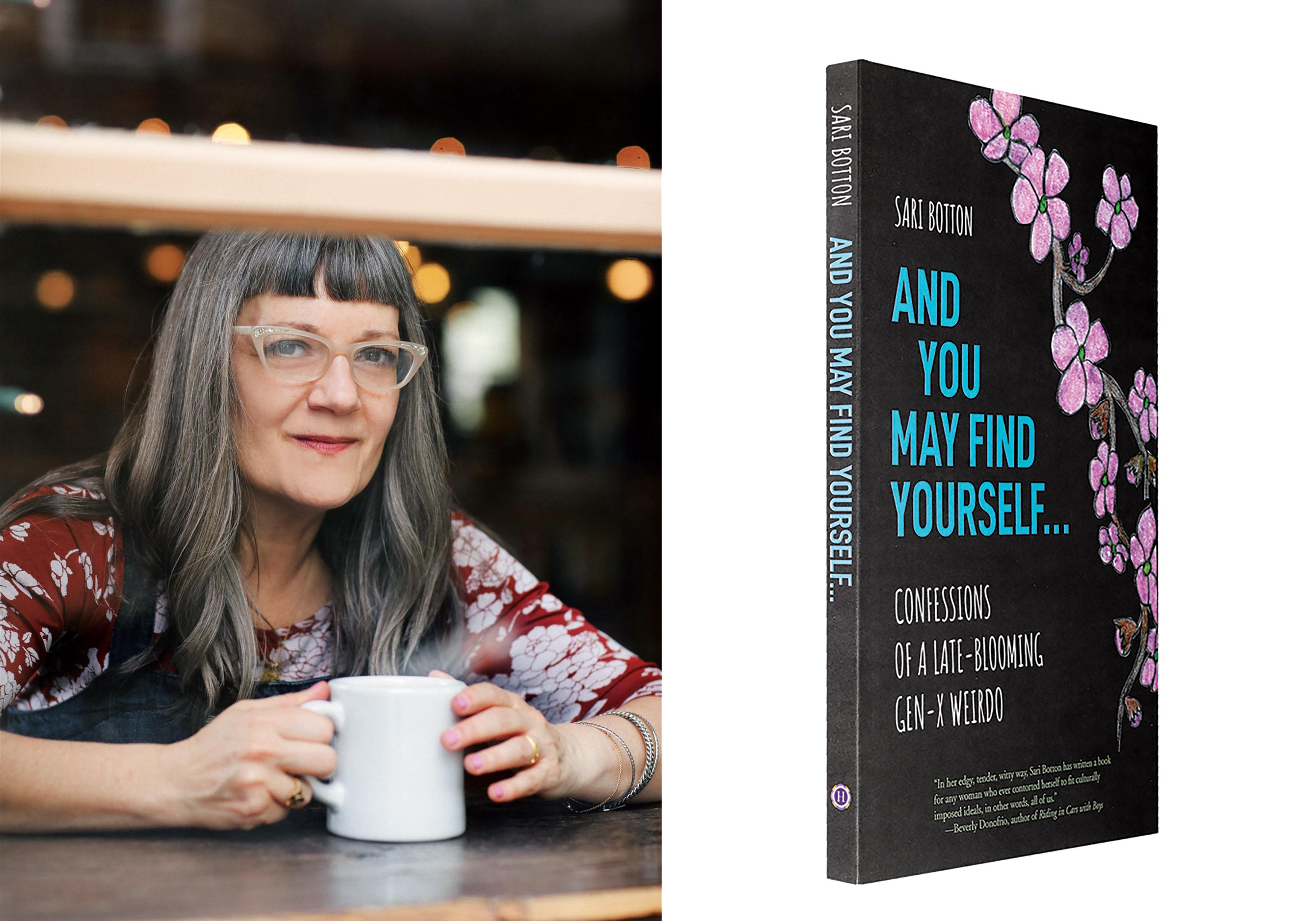

Sari Botton

Age: 57. Residence: Kingston, New York. Book: And You May Find Yourself: Confessions of a Late-Blooming Gen-X Weirdo (Heliotrope Books, June 2022), a memoir-in-essays about coming “of age” to feminism and self-actualization as an older person, discovering the courage to resist conforming to fit in, and realizing how maybe it’s never too late to find your way. Agent: Melissa Flashman. Editor: Naomi Rosenblatt.

I encountered many obstacles on the path to publishing my debut memoir-in-essays, And You May Find Yourself: Confessions of a Late-Blooming Gen-X Weirdo, at fifty-six. But without a doubt, the biggest obstacle standing in my way was yours truly. For too long I let my fears and self-doubt interfere with my commitment and focus while I hid myself behind my work as a ghostwriter and editor.

I always knew I wanted to write a memoir but felt conflicted about it after a few personal essays I published early on upset people in my life. It left me gun-shy about engaging in a kind of writing that exposes others, especially those who’d prefer to remain incognito. I’d also made some bad choices with regard to exposing myself—particularly in my mid-forties, during the early twenty-teens. In those days I let low-quality websites publish half-baked essays of mine in which I revealed some of my worst relationship choices without fully processing them and making meaning of them.

I hadn’t fully given up, though. For years I was still writing—just intermittently and tentatively. I invested a great deal of energy in a sort of side quest: trying to determine the most ethical way to approach writing about other people. To that end I interviewed many memoirists about how they handled it. I learned that solutions to this problem weren’t one-size-fits-all; different writers approached this in their unique ways, informed by their own experiences and senses of morality.

Through those conversations, over time, I came around to a system that felt right for me: First, I wrote a warts-and-all “vomit draft” that I didn’t intend to publish, to get the hardest parts of the story out of my head—so I could feel emotionally unburdened by them and look at them from different angles. I allowed some time to pass before the next draft, so that I could process and gain meaningful understanding of the more difficult parts I wrote while finding compassion for myself and others. With each draft I blurred people’s identities to a greater and greater extent. With an eye toward generosity, I extracted any unnecessary details of other people’s choices and behavior. I worked to get the stories to a state in which they were no longer just about me and the specific people I included but more broadly about common cultural phenomena that others would relate to. Before publication I showed the work to people close to me who figure prominently in the book.

Despite having figured all that out for myself, I remained reluctant, so I interviewed even more memoirists. At some point in my early to mid-fifties, I realized that in continuing my “research” I was stalling. I’d also started to resent the work I was doing editing and teaching other, mostly younger writers, ushering so many of them in the direction of book deals while neglecting to pursue my own. What’s more, in the back of my mind was the realization that both of my grandmothers had died around my age—one at fifty-one, the other at fifty-five. Here I was wasting time, yet who knew how much of it I had left?

It was time to buckle down. In 2019 I finally did, polishing the book proposal I’d had in the works for a few years. I gave it to my agent, who took it out to some traditional publishers. I was excited for about two weeks. Then one by one they passed, and it messed with my already shaky confidence. I was overcome with impostor syndrome. Who was I to think I had permission to write my memoir? To believe that my story and voice mattered?

Then a friend shared with me a list of small indie presses she’d compiled. I got my agent to submit to some, including Heliotrope, a tiny publisher based in New York City’s East Village, where much of my story takes place. Editor and publisher Naomi Rosenblatt not only got my book; at a lunch at Café Mogador during which she made her offer, she basically sold my book to me, explaining why it was necessary: that there were people of all ages who would see themselves in my midlife coming-of-age book, which was also about feeling out of step with peers and finding the courage not to conform—things that many can relate to.

She was right. Since publishing my book in June, I’ve received messages from readers of all ages and genders letting me know how various essays really spoke to them. It’s been incredibly validating.

But before I could get to this happy place, while anxiously writing the book through the worst of the pandemic, I had to keep myself from quitting. Actually, it helped to give myself permission to quit. When I lost faith in myself and the book—when people were dying and I thought, who cares about my stories of not fitting in?—I would envision a Zoom chat with my agent and editor during which I told them I was throwing in the towel. Usually this happened in the wee hours of the morning. But then each time when I arose, I recommitted myself. I realized that after so many years of working on this material, it was now or never—that if I bailed on my hard-won book contract, it could damage my reputation, end my relationship with my agent, and put me even further afield from my lifelong dream.

Eventually I finished a draft. I put it through two more rounds of blurring and what I call “declawing,” as in taking out anything that might be unnecessarily hurtful. Finally I arrived at a draft that I could get behind.

Once the book was out I was presented with a new challenge: I had to get the word out about it, mostly on my own. I’ve loved working with a tiny indie press and recommend seeking publication with one if you’re having a hard time landing a traditional deal. But having to be a squeaky wheel for my own work is uncomfortable. I struggle to find the chutzpah necessary to say, please pay attention to me, a writer with a tiny press, a middle-aged woman no less, the kind of person you’re used to not seeing.

Thank goodness for the readers who keep reaching out with positive feedback after they get and read the book—mostly on my recommendation. It reminds me of why I must keep spreading the word—and stop feeling uncomfortable about it.