In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 137.

When writers discover that I am a psychoanalyst, they often ask whether I think psychoanalysis can be helpful to the creative process. It seemed to help Samuel Beckett, who was in analysis with Wilfred Bion, I tell them, and H.D., who was analyzed by Sigmund Freud. But even without taking the plunge and going into an analytic treatment, a writer can benefit from thinking about their work through the lens of psychoanalytic principles. One area in which psychoanalytic thinking can be particularly useful is in understanding the unconscious dynamics that are at play in selecting your imagined reader.

A key concept in psychoanalysis is transference: We transfer expectations and emotions developed through experiences with people from our past onto figures in the present. If your father challenged your ideas in a mocking way when you shared them at dinner, for example, you may expect the instructor of your writing workshop to similarly take you down when you present your work to the group seated around a table. The more important the person from your past was to you—a primary caregiver, for instance—the more likely you will be to anticipate their responses from people you encounter in the present, your imagined reader included.

The figure you address when writing shapes your work through a psychological process literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin terms “addressivity.” In the split second before speaking, we project ourselves into the position of our addressee, imagine how they will take what we are about to say, then adjust our communication to fit those expectations. Addressivity explains why you can feel “on” while talking to one person but awkward, or bored, when talking about the same thing with someone else. This mechanism, performed in milliseconds, leads us to alter spontaneous expressions to account for how we predict our addressee will think and feel.

If your imagined reader is based on a person from your past who was judgmental, you will likely imagine and anticipate a critical response and adjust your writing accordingly. It’s important to note that the adjustments you make will aim to protect against being viewed critically, not to improve your writing. In other words, you risk sacrificing your writing in the interest of preserving your image of self—in your own eyes and in the eyes of your imagined reader, which are essentially the same, as you are projecting yourself into the reader’s position in imagining how they will respond. Thinking about transference can help you disentangle the work from the interpersonal issues in your life. If you don’t give thought to your imagined reader, you are likely to unconsciously adopt a figure based on a real person from your past. I’m always surprised by how often writers unknowingly address imagined readers who are rejecting, critical, or demeaning.

Why not be proactive and consciously choose your addressee instead? There’s a classic poetry writing exercise that taps into the dynamic of addressivity: Write the same poem four times, addressing each draft to a different figure—your lover, your mother, your childhood self, an editor at a well-known mainstream magazine. The exercise gets at how our writing changes according to the figure we conjure as our addressee.

Bakhtin suggests we address a “superaddressee,” a “(third), whose absolutely just understanding is presumed.” For some writers, this ideal reader is an “indefinite strange[r],” in critic Michael Warner’s terms, a figure that allows you to speak into a “social imaginary,” an “environment of strangerhood [that] is the necessary premise of some of our most prized ways of being.” How might your writing change if instead of addressing your harshest critic you imagined your reader as a superaddressee, an indefinite stranger, your most affirming friend?

Nuar Alsadir is the author of Animal Joy: A Book of Laughter and Resuscitation (Graywolf Press, 2022) and the poetry collections Fourth Person Singular (Liverpool University Press, 2017), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best Collection in England and Ireland, and More Shadow Than Bird (Salt Publishing, 2012). She works as a psychoanalyst and psychotherapist in private practice.

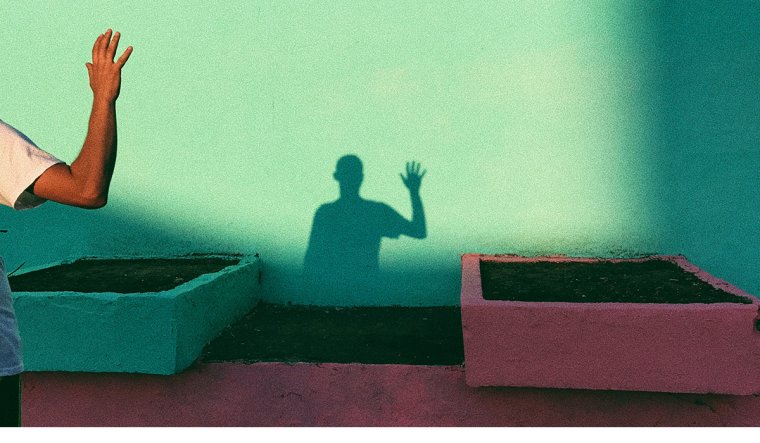

Art: Ioana Cristiana