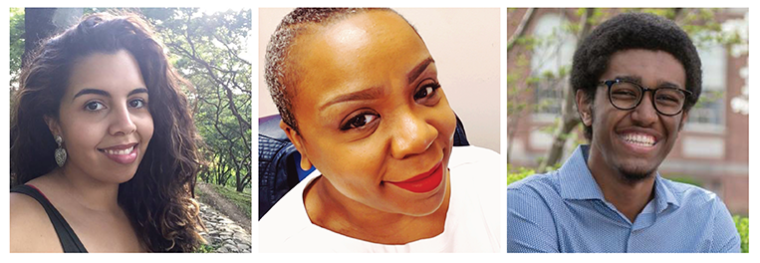

When Ferguson Williams, a fiction writer from Socastee, South Carolina, received an e-mail informing her she had been accepted to PERIPLUS, a new mentorship collective serving BIPOC writers across the United States, she could hardly believe it. “I kept reading it in my head like an NBA announcer would, complete with the microphone echo and the cheering crowd,” she says. Williams is one of fifty-five PERIPLUS fellows chosen for the collective’s inaugural class of mentees from more than 1,400 applicants. Through the collective, each fellow has been paired with an established writer working in the literary arts or in journalism for a year of mentorship. While some of the collective’s mentors also teach professionally, all mentors volunteer their time to demystify and democratize the world of writing and publishing for BIPOC writers.

From left: Amaris Castillo, Ferguson Williams, and Jonny Teklit. (Credit: Teklit: Deb Grove)

“It started small,” says Libby Flores, currently the director of audience engagement and digital projects at BOMB magazine and one of the inaugural mentors in PERIPLUS. “Writer Vauhini Vara e-mailed other writers—R. O. Kwon, Esmé Weijun Wang, and Rachel Khong. She asked if there was a one-year mentorship project for BIPOC writers where emerging writers were paired with more established authors in the field.” The answer was no. And so more e-mails circulated. “It became a collective with many members really quickly,” says Vara. Soon they decided on a mission for the collective—to provide fellows of all ages with mentoring and guidance so that they can achieve their professional and artistic goals as writers—and a vision: to make the publishing industry more welcoming and accessible to BIPOC writers, who have been historically excluded from it. Vara announced the call for applications on Twitter. “At the end of our inaugural year,” Flores says, “we hope that writers, who felt isolated and not seen, feel fostered going into 2022—not just with what they have accomplished on the page, but also in the esteem they have as BIPOC writers in the world.”

While there may be no lack of aspiring authors who are hungry for advice, the writing and publishing world often needs more people willing to share it, or a structure through which they can offer that expertise. As fellow Jonny Teklit, who will be mentored by poet Tiana Clark, author of I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018), says, “I come to this fellowship an eager student.” He, along with the other fellows, will converse with their mentors for a half hour every other month about topics such as daily writing routines, craft concerns, paths to publication, graduate school, and finances. A statement from the collective says that most mentors “have also committed to reading and giving feedback on mentees’ work.”

“We’re a collective of writers who want to, and are able to, make ourselves available. We like the idea of a low-key, informal, mutual-aid-style project that exists outside of institutions,” says Flores. Access, mutual support, and transparency are among the collective’s core values. As such, some mentors are also organizing events and resources for all mentees. Nicole Chung, author of All You Can Ever Know (Catapult, 2018), for instance, is planning a panel for later this year during which book editors will share advice with fellows.

While the collective aims to serve BIPOC writers, not all the mentors identify this way. Flores says that BIPOC writers are often the ones to carry the emotional labor of advocating for better representation. “It felt powerful to include white writers who we knew to be allies,” she says. As mentor Alex Marzano-Lesnevich, author of The Fact of a Body: A Murder and a Memoir (Flatiron Books, 2017), says, “The system is set up with gatekeepers—so let’s help pry open those gates. As a queer, and now out as trans, person, the idea that I could help connect other queer writers with resources was profoundly important to me. Publishing is still predominantly white, predominantly cis, and predominantly heterosexual. Let’s change that.”

Fellow Amaris Castillo’s goals include pushing past insecurities and writing bravely. She wants to produce short stories she is proud of and to make progress on the novel of her dreams. Castillo, who will be working with Natalia Sylvester—whose most recent novel, Running, was published last year by Clarion Books—is grateful for mentors so consciously lending their support to rising BIPOC writers. “It’s generous of the mentors to give of their time and share lessons learned,” says Castillo, “especially those embedded in a publishing industry where there is still so much work to be done when it comes to diversity.”

The deadline for the 2021 program has passed, but PERIPLUS will accept applications for its 2022 cohort in late 2021. Those looking for more information can e-mail peripluscollective@gmail.com.

The collective hopes to make lasting change in the industry for BIPOC writers, as its name evokes: The word periplus means to voyage, to circumnavigate. It also refers to a log that captains used to chart their way across harrowing waters in order to aid future sailors’ navigation. In many ways, Flores says, that is the essence of mentorship: “It is our way of showing new writers the record of our voyages in the hopes that they divine some meaning for their own journeys.”

Jennifer De Leon is the author of Don’t Ask Me Where I’m From (Simon & Schuster, 2020) and White Space: Essays on Culture, Race, & Writing (University of Massachusetts Press, 2021), winner of the Juniper Prize. Visit her at jenniferdeleonauthor.com.