For years, manuscripts—handwritten, hunt-and-pecked, ink-smudged—have trickled in with the mail for the San Francisco Public Library’s Presidio branch. They come from aspiring authors in search of an unlikely home for their work: a library based on a book based on a library.

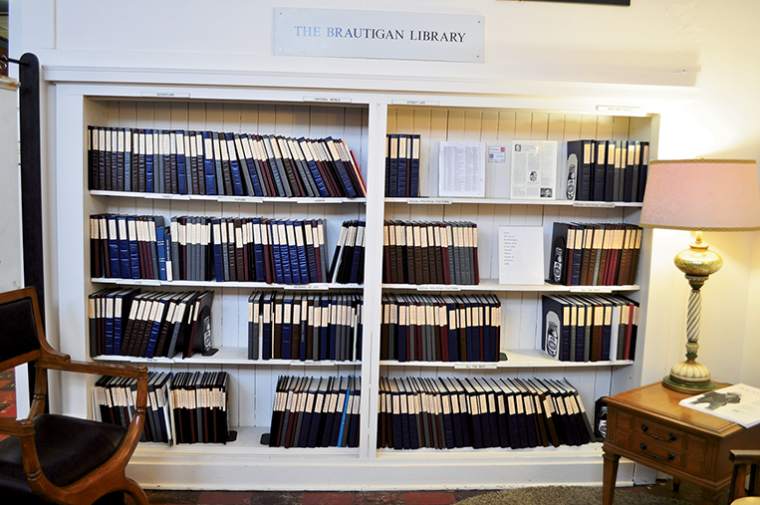

“Einstein Doesn’t Throw Dice” and “A Great Big Ugly Man Tied His Horse to Me” are among the titles of manuscripts in the library’s collection, pictured above in 2015. (Credit: Joe Mabel)

Specifically the manuscripts are meant for the fantastic archive of unpublished books depicted in novelist Richard Brautigan’s counterculture classic The Abortion: An Historical Romance 1966. But while the Presidio branch inspired The Abortion’s peculiar library—its photo graces the book’s cover, and they share the same address—the unique repository is strictly the stuff of fiction. Or, at least, it was the stuff of fiction. Today it is also a very real place located 650 miles to the north of San Francisco, in Vancouver, Washington. Known as the Brautigan Library, two rows of bookshelves in the Clark County Historical Museum represent The Abortion’s library made manifest, a home for more than three hundred unpublished, bound manuscripts from all around the world. Here visitors can sit in wooden chairs or lie down on the fuzzy, multicolored rug and explore the dreams of strangers.

The Brautigan Library was first established by Todd Lockwood in Burlington, Vermont, in 1990. A longtime Brautigan devotee, Lockwood reread The Abortion every year for fifteen years, in part to revisit its setting: a public collection to which anyone could contribute, unaffected by publishing trends or ideas about what makes stories commercially viable. After the loss of his sister in a plane crash, Lockwood felt compelled to make the library real, a story he detailed last year in an affecting episode of public radio’s This American Life. (“Those things that you’ve been thinking about doing for a long time all of a sudden get moved right up to the front burner,” he said.) His collection soon amassed books with titles like “Allan, You May Use Your Ballpoint Pen Now”; “I’d Be Your Roadkill, Baby”; and the self-explanatory “Random Thoughts.” Instead of the Dewey decimal system, Lockwood and his team of a hundred volunteers organized their materials using the “Mayonnaise System,” named for Brautigan’s favorite word and including categories such as WAR (“War and Peace”), MEA (“Meaning of Life”), and ALL (“All the Rest”).

Such exuberant whimsy typifies Brautigan, whose style mixed practical and readable prose with moments of surreality and keen observation. In works like Trout Fishing in America, Brautigan ably straddled the aesthetics of the Beats and hippies, managing to both touch something essential in the zeitgeist of the late 1960s and find fabulous success and fame. But as American culture tilted into conservatism, that same work was increasingly dismissed; he died by suicide in 1984, at age forty-nine.

Although Brautigan’s work continues to inspire devotion bordering on obsession for some, the volunteer pool at Lockwood’s library—and its submission rate—gradually shrank. During the late 1990s the manuscripts lived on a shrink-wrapped pallet in Lockwood’s basement—until John Barber, an old student of Brautigan’s and now an expert on his writing, got in touch, offering to move the collection to its current home. Since then the Brautigan has stopped taking new physical submissions, transitioning with some success to PDFs. Last year the library’s online repository had forty-one thousand unique visitors.

One of the most beloved chapters of The Abortion, titled “The 23,” recounts the twenty-three books submitted to the fictional library over the course of a day. One book is brought in by a scientist, another by a chicken farmer; several are delivered by children. Real-life contributors to the Brautigan are similarly diverse: chemists, pastors, eldercare workers, people who have traveled the world or who have never left their small towns. They submit their manuscripts for reasons that are just as varied: because they find the layers of metafiction so delightful, because they want to share their work freely and for free, because they believe their writing has no chance of being published elsewhere.

During the library’s pre-internet Vermont days, publishing was the only option for writers who wanted to “touch the future,” as Barber puts it. “Publishing a book was a way of achieving immortality,” he says. Lockwood thus describes the library mix of manuscripts as a sort of anti-bookstore. “This collection did not look like the slush pile at Simon & Schuster,” he says. “People were not trying to do this for career purposes.”

Ronnee-Sue Helzner, whose father, Albert, was the library’s most prolific author, sees the Brautigan as providing a literary home for people like him: Albert Helzner was a chemical engineer who was driven to write by an enduring passion for the medium. His sixteen books weren’t “packaged for publication,” she says. “They don’t have to be, at the Brautigan. It’s a home for ideas.” When Brautigan’s daughter, Ianthe, considers the library, she notes that her father includes himself in the authors bringing manuscripts to submit in “The 23.” She wonders if inserting himself in the march of people looking for a place to share their stories was his way of affirming—and continuing to seek—human connection, of proclaiming that “no matter where and no matter how, it’s the quality of being heard that matters. Even if you’re famous, are you heard?”

That’s also what Helzner suspects her father was after in his many submissions. The Brautigan conveys an attitude of what she calls “tremendous respect for all people,” a conviction that their stories deserve to be read and considered. “I think the Brautigan is a statement that you, like anyone, are valued—as a writer and as a human being,” she says.

The world has changed a lot since 1990. The role the Brautigan plays today is necessarily altered by its coexistence with Medium blogs and Kindle singles. For library contributor Greg Moore, the Brautigan makes a reliable repository for the work he hopes will be his legacy, unlikely to be replaced by a hot new app, suddenly subject to character or word limits, or put unceremoniously behind a pay wall. “I’m getting to dandelion age,” Moore says. “I blow, and the things that I do in this life go out and do whatever they’ll do outside of my little realm.” He likes to imagine someone might stumble upon his manuscript and enjoy it. That idea is enough.

Alissa Greenberg is a writer based in Berkeley, California, who reports stories at the intersection of culture, science, business, and international affairs, with a generous dose of quirk.