This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Zefyr Lisowski, whose new poetry collection, Girl Work, is out this week from Noemi Press. In these unflinching poems, Lisowski contemplates womanhood as a kind of labor, one performed under the weight of history, stifling social arrangements, and troubled memory. Interrogating the nature of childhood trauma, the poems envision it as something like a horror-movie curse, casting the speaker into a cycle of traumatic repetition via fraught encounters that occur both out in the world and within the psyche. The reader follows the speaker through sidewise accounts of these traumas alongside narration of everyday experiences, appraised with a critical attention that frames them as products of interlocking systems of oppression, which grant the speaker varying degrees of privilege and precarity: Her whiteness offers protection even as her trans identity makes her a target for violence. Refusing to indulge feelings of self-pity, the speaker nonetheless moves toward a position of self-compassion, one necessary for survival: “Poem, I don’t need to tell you what happened, / but I’m finding myself in it even as we speak, as I write / again toward this body so many / have written on already.” Zefyr Lisowski is the author of the poetry collection Blood Box (Black Lawrence Press, 2019). A poetry coeditor of Apogee Journal, she is also a 2023 NYFA/NYSCA Fellow, a 2023 Queer|Art Fellow, and a recipient of support from the Tin House Summer Writers Workshop, Blue Mountain Center, the Center for the Humanities, and Sundress Academy for the Arts. Her new book, Girl Work, is the winner of the 2022 Noemi Book Prize.

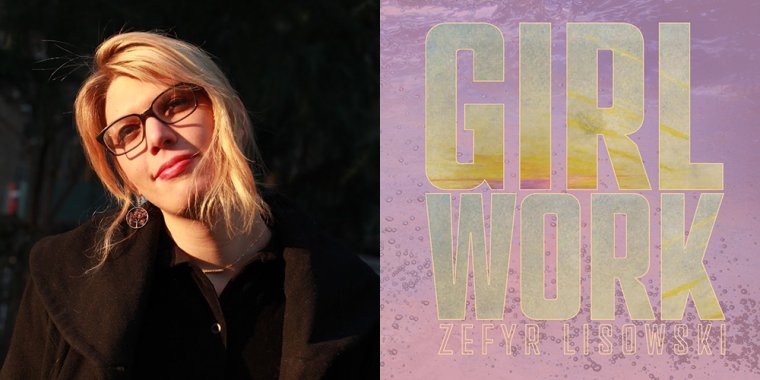

Zefyr Lisowski, author of Girl Work. (Credit: Ayesha Raees )

1. How long did it take you to write Girl Work?

I wrote the first poem at a haunted arts residency at a former robber baron’s hunting lodge in 2018. I finished the first draft of the book approximately a year later. That said, I continued working on Girl Work, in various forms, until 2023—although the last major revision was in 2022, before I sent it to Noemi. While editing I tried to preserve the me who I was when initially writing it—messy, at times vindictive, sometimes wrong, and committed to a language of directness. Time has softened all of those things, but I still respect who wrote that initial draft, even if she feels more like a stranger now.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The book started in response to the whiteness (and wealth) of the most mainstream iteration of #MeToo. Around the same time as the #MeToo movement’s 2016 mainstream resurgence, I noticed a more localized trend among white trans people of talking about transness as a state of death, independent of class or race. In both of these trends, differently classed experiences of sexual and physical violence were collapsed into the same experience, and womanhood was positioned primarily as a deracinated state of victimhood or ruined innocence. I myself am a recipient of violence, many times over. I also am a laborer. I also am white, which serves as a mitigator of the intensity of the frame and was an identity notably left out of many mainstream #MeToo discussions. I was interested in writing a book that spoke to these intersections of class, race, and sexual violence while refusing to ascribe a redemptive or palliative “goodness” to the speaker—to live more in the mess.

So the most difficult thing about the book was writing about violence without positioning the speaker as a perfect victim—looking at the messy ways that sexual violence, labor, and emotional cruelty led the speaker to, at times, a cruelty of her own. Or perhaps the most difficult thing was writing about what scholar Achille Mbembe terms “necropolitics”—the politics of who is granted death and who is granted life in a society, with death often ontologically inscribed onto Indigeneity and Blackness—without foreclosing the potential of life for the subjects about whom I was writing. This was difficult, in part, because I don’t think I fully pulled it off; regardless of the care I took, including during the revision process, Girl Work is still a wound of a book. But those central concerns still animate the whole of the text, the gristle on which I chew.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’m an inconsistent writer, a disposition caused in part by the other waged labor I do and the conditions of capitalism; I write when I’m able to write. Sometimes daily, often weekly, occasionally monthly. But I think about writing every day, which I suppose is a sort of writing itself. The exception to this is at residencies, where I’m prolific in both my reading and writing: Again, capitalism.

In terms of where I write: my bed, or my desk, or stretched out on the floor, tummy down. When: late morning and late evenings. Pre- and post-work. When feeling lonely, or not. Writing, initially, was a way to access love without the fear of loss. As I’ve grown, it’s become a way to know loss and love sound like almost the same word anyway, to find care in that nonetheless. Now I write for myself. But I also write to show what I’ve written to lovers, friends, community—to get back from them in turn. Regardless of where, when, or how, I write to receive.

4. What are you reading right now?

Currently I’m reading Diana Khoi Nguyen’s second poetry collection, Root Fractures, and I just finished Jules Gill-Peterson’s brilliant, incisive A Short History of Trans Misogyny. As a birthday gift my girlfriend got me the complete novels of Lynn Ward, the leftist woodcut illustrator whose wordless novels paved the way for the modern graphic novel; I’ve been savoring my way through them. Similarly languorous and brilliant is Clarice Lispector’s The Hour of the Star, which I read during a recent hospital stay, sparking a renewed interest in her work; I’m following it up with The Passion According to G.H. And of course I’m always reading the work of my friends. I’m especially excited about Cyrée Jarelle Johnson’s Watchnight and have read some brilliant essays and poems by Sloane Holzer I can’t wait to see in the larger world. Finally, since her passing, I’ve been rereading the funny, transformative work of luminary activist, mother, and revolutionary Cecilia Gentili. If you haven’t read Faltas, do so immediately.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

When I first wrote this book I structured it around the spiral—the circle of the well from the 2002 film The Ring, the conviction that this (labor, gendered violence, the aforementioned necropolitics) will keep happening, the anguish of repetition. I wrote out of a desire to see the thing unguarded, whether that thing be beauty or violence; and I wrote out of a lack of faith in terrestrial redemption. That version of the book was nearly published several times, and I still hold tenderness for its tenderness. But after several years, a minor breakdown, and a complete reconfiguration in my understanding of what my life could look like, I started to hope; and I realized that while the book is haunted by repetitions, love repeats thematically too. From there I started threading more poems into the collection that cared for, rather than cut, the reader—and gradually the spiral uncoiled. Now the book is structured around descents and ascents, which feels more honest—or at least more complex. The last significant change in the collection happened when my editor, Diana Arterian, suggested moving the poems that laid out the concerns of the book most explicitly—whiteness, violence, labor, and beauty—to the first half of the book. This provided space in the second half for a more capacious kind of holding as well, a more total transformation of the speaker’s relationship to herself and the world.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

The short answer is no. The long answer is maybe. My MFA was a fraught but incredibly generative experience: I wrote a whole first draft of the book there, and I was also told by a classmate that by writing about the whiteness and transphobia of the program in said book, I was “shooting my allies.” The program was fully funded; I received outstanding feedback on the first draft of the book; I was miserable. That said, I’ve been able to professionalize as a writer in part because of the credential of the MFA. And since the MFA I’ve built back my sense of community, which I had grown disillusioned with completely for several years. Which is to say: The damage wasn’t permanent. I think MFAs are rooted in white supremacist, ableist, cisnormative standards, although there are certainly programs that don’t follow those fault lines of power. I think that for anyone minoritized in our society, any interfacing with systems of power needs to be tactical and very intentional. But I don’t think that precludes going for it anyway. Just to be safe: If you’re considering a program, don’t go into debt. Try not to move somewhere you wouldn’t move already. And outside the program surround yourself with those who love you enough to be honest. Living, I believe, not working, is the work.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Girl Work?

The book started from such a despairing place, so the fact that it wrapped back around to a state of hope by the end of the writing process was a balm and a gift. But maybe that’s to say I was surprised at how my life changed, and the work reflects that life. Life, after all, is a form of active revision too. Growth shouldn’t only happen on the page.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Girl Work, what would you say?

Not to sound like Dan Savage, but: Things will get better. You will heal, surround yourself with those who love you and those you love. Grief complicates a life but is also a measure of care and, as such, it enriches it too. Continue working on multiple projects beyond this one—they’ll buoy you. Rest more. Nurture your relationships. Let it cook.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

At a reading I gave in 2018, early in the writing process for this book, an audience member came up and told me, “You must have gone through a lot of therapy to write this.” It was such an (accidentally?) accurate read. I’m skeptical of a lot of things about therapy—at its worst, it individualizes systemic problems—but I have to acknowledge the ways it helped me. Before I wrote the book, I started thinking through it; and before I started thinking through it, I felt it through. Therapy helped me feel.

So much of Girl Work is about embodied trauma, so writing it was an exercise, often unsuccessful, in avoiding retriggering myself. Things that helped: working in forms that had their own containers built into them (which is why there are so many visual poems cropped in by the dimensions of the page and long columns of text in the book). Taking frequent walking breaks. Smoking herbal cigarettes. Watching movies with friends. Pursuing other hobbies (teaching myself how to play banjo, building a dollhouse, writing and recording a musical based on The Ring, getting back into drawing comics). Laughing. I couldn’t have written the book without all of these.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

My Queer|Art mentor, T Fleischmann, told me once that I sometimes use the lyric to avoid naming more difficult truths. So many of the writers who are most important to me, such as June Jordan, engage in a poetics of directness, a way of naming and not looking away from machinations of power. I love the delights of a pretty line or sentence, but often they obscure rather than clarify. T’s dictum to say the thing directly is hard because it requires a deep vulnerability and conviction of purpose in my words and acts. I strive for that bravery every day.