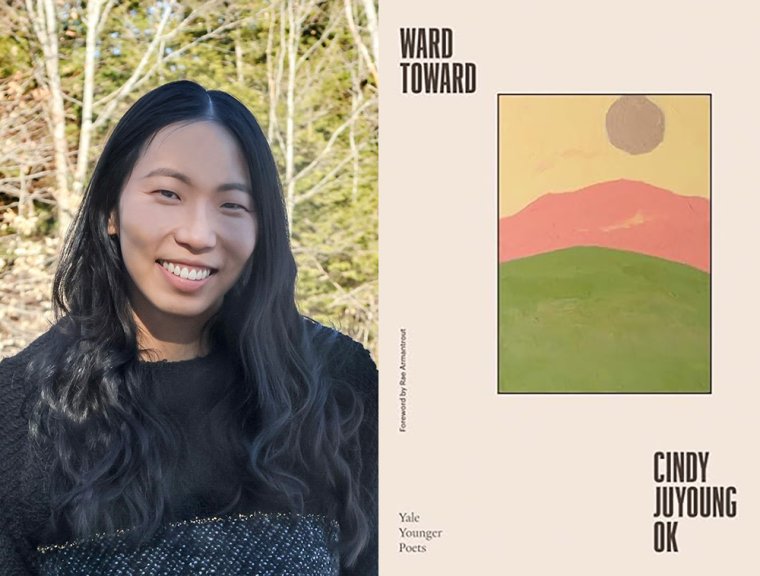

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Cindy Juyoung Ok, whose debut poetry collection, Ward Toward, is out today from Yale University Press. In these sharp poems that range from traditional lyrics to formal experiments, Ok presents a personal narrative of identity formation amid a struggle with mental health as well as a critical dismantling of received ideologies and traditional ways of seeing the self and others. With bleak humor, an eye for the absurd, and careful attention to the line, the poems offer a window into the Kafkaesque labyrinth that is the U.S. medical establishment, elegiac analyses of racist violence—particularly against Asian Americans—and critiques of popular culture. In her foreword poet Rae Armantrout, who selected Ward Toward for the Yale Series of Younger Poets, calls the collection “radically honest and unpretentious.... Cindy Juyoung Ok is a wonderfully inventive poet with a command of her craft.” A writer, editor, and educator, Cindy Juyoung Ok is a MacDowell Fellow whose poems have been published in the Nation, the Yale Review, the Massachusetts Review, and elsewhere.

Cindy Juyoung Ok, author of Ward Toward. (Credit: Joanna Eldredge Morrissey)

1. How long did it take you to write Ward Toward?

Four years. Its oldest poem is from autumn 2018, and its newest poem is from autumn 2022.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I had understood a first book to be all one’s successful poems put into a manuscript as though a shrine to a period or a portfolio of competence. Only once I gave up the urge to stuff individual pieces into a document as an archive of the ego could I write the book. The phrase “ward toward” came late but felt like receiving a revelation, upon which I formed a shorter manuscript that was a wholly separate entity from the storage unit I had accumulated. There are poems I find taut or elegant or even relevant to the book’s concerns that were not included. I thought a book could be carved out of a block of poems, but instead it had to start from blank space.

The most practical challenge of writing the book was not having workplace health insurance for the first year and most of the last year. I received insurance through the Affordable Care Act but did not get off the wait list for a primary care physician. It would have been much easier to write if health care were as accessible as it is when my contracts are full-time with school districts or universities.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Nothing ritualistic. I write on pads when I have something to write with, which can be during any hour or season and with seemingly undivinable frequency: three ready poems at once, not a line for nine months, and so on. It brings me only annoyance to force consistency or write bad poems. I don’t find that they lead to more interesting ones so I prefer to wait until ready poems seem to exist to me whole. I usually write in bed or on a couch, and when those are unavailable I resort to a desk.

As a process, writing is like pooping. I try not to push it, and I hope that all my passive non-writing activity is digesting well and can become, through my trusty body, something new. Strain is not often necessary. The products, though, differ: What comes out in a poem is, I hope, the best and most concentrated bits of me, parts I could never hold in and which can live beyond my one mind and small life.

4. What are you reading right now?

[…], which Fady Joudah mostly wrote this autumn during the ongoing U.S.-backed genocide of his people in Palestine. I include poems from his collection at my readings (with his knowledge and blessing, as we share a publication date and are reading each other’s books now), and I am grateful for the book’s wildness and precision, for the fathomless generosities he offered in these poems and also personally in this period: When I lost income, he offered aid; when I received an unfavorable medical diagnosis, he offered, as a physician, to discuss its details with me.

While writing recently on a piece by Christine Imperial that undoes the visuality of U.S. colonization in the Philippines by marring texts by Dean Worcester, I was disquieted to realize the extent of National Geographic’s complicity in creating the visual imaginary of the other, of colonialism’s needs and ends in the U.S. I started reading the images and texts of issues from various years, and they are terrifying, amazing, telling. In news of another sense, I’ve begun The Smell of Risk: Environmental Disparities and Olfactory Aesthetics by Hsuan L. Hsu, who considers in daring detail how the Western aesthetic project has categorized and metaphorized smell, how art makes sense of air.

And I am always reading student work. After reading the reviews in Anthony Cody’s Borderland Apocrypha (found from Trip Advisor) and Courtney Faye Taylor’s Concentrate (created in Yelp form), my student Avery began collecting and working with beauty-product reviews, crafting pieces in which the speaker has experienced pain or even hospitalization because of a product but hugely recommends it because it works, or they feel happy. Her poems and prose discern this pattern but are careful not to satirize the review writers or blame any individual for the structures at play, and extensive research on daily performativity clearly intrigues her impulses.

5. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

The poems are formally constrained in their enactment of material constraint, as with boxed stanzas. So their arrangement also has a stringent logic in three sections, or “wards,” with reiterative transitions between adjacent poems.

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I neither particularly recommend nor argue against graduate school, but funded programs provide a way to structure time differently than many jobs. For a public school teacher to suddenly have the option to wake up without an alarm and read or cook—it moved my mind, even as I planned to return to my full-time job and imagined the degree as a break from a nine-to-five that was more like six-to-six. I lived reasonably on my stipend and additional gigs, which was not as feasible for those with costly roles as family caregivers or with major student debt, or as relevant for peers who were financially supported by parents or partners.

Most of my writer friends I met at residencies, conferences, and readings, and all my publications and jobs came through applying to public calls. Having the degree was not a prerequisite for my job as an incoming assistant professor in an MFA, and there is so much evidence that there are no true prerequisites to writing itself.

7. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Ward Toward?

It surprises me still that I wrote Ward Toward alone. No one had read it when I sent it into just one contest, whose screeners and then contest judge were the first ones to meet the book. My friends are thankfully the basis of my days and years in all ways, and my spouse is otherwise my thrillingly brilliant first and last editor, so it is unusual that the making of a major undertaking, one I felt proud of, happened this way. If I publish another book, I hope I will be able to describe writing it alongside and through and because of many others.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Ward Toward, what would you say?

Nothing related to writing: Buy a water filter. As your grandparents continue to die off realize how many people raised you and how devotedly. Apparently soap is different from face wash. The city provides free radon tests. The pain of your wishes coming alive is preferable to the pain of the alternative.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

Most of what I did was not writing. I taught at a dozen universities and nonprofits, moved to and left nine cities, attended hundreds of dinner parties. It can hardly be called work, but time passed and the poems happened. Writing the present yields my dullest stretches of words. To make poems I need to live and have such a distance that there is no catharsis to be sought or risked.

Before turning the book in for production, I also contacted everyone mentioned in its pages, even if unrecognizably, and cited any conversation I felt was referenced. This included calling my childhood friend in prison, checking every relevant line with my mother, and tracking down a retired group therapist from a decade prior who had no recollection of me but was pleased with my recounting of our interaction. I hoped not for permission necessarily but to prevent surprise. Happily, everyone was supportive of the book and delighted to be included.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Two years ago I used the word “grooming” to refer to a short story character’s routine of hair brushing and face washing. My students momentarily recoiled and then explained that my usage of the word seemed strange, as they experienced the primary meaning of the verb as the initially metaphoric one: to manipulate, usually younger people, toward sexual and other violent ends. The exchange was a piece of writing advice these writers were providing me:

You cannot refuse language’s constant renewals by claiming nonparticipation. The meaning of all words is socially determined, and their users are a part of, and responsible for, their changing possibilities.