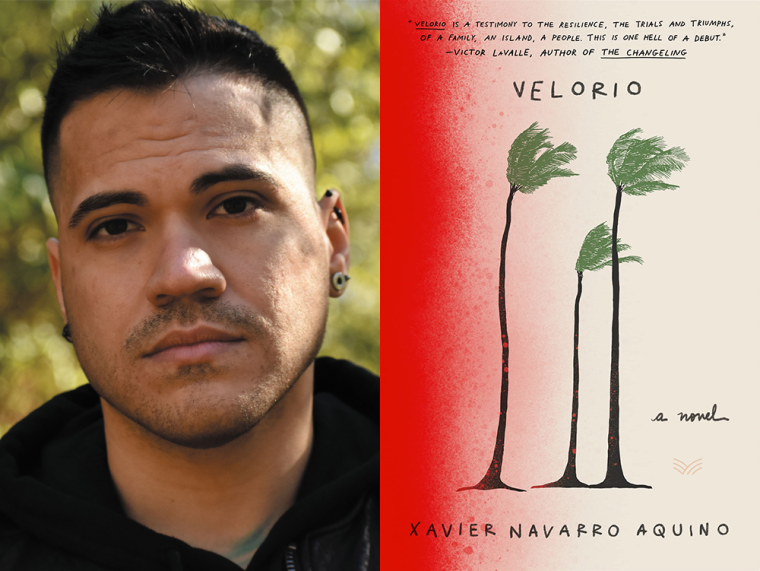

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Xavier Navarro Aquino, whose debut novel, Velorio, is out today from HarperVia. The arresting first line of Velorio immediately conveys the heartbreak of Hurricane María for Puerto Rico. A young girl named Camila reflects, “It wasn’t until after I dug out her body that I learned to love my sister, Marisol.” Velorio follows Camila and several other characters as they converge on a cult-like alternative society known as Memoria, established by a man name Urayoán in the aftermath of the hurricane. Polyphonic and lyrical, the novel renders and resists the legacy of empire in Puerto Rico and the authoritarian shadow that accompanies disaster. “Velorio recognizes that neither utopia nor dystopia are finite states, that they exist alongside and even inside one another, like the hurricane and the eye, the empire and the island,” writes Justin Torres. “Xavier Navarro Aquino takes us on a riveting, harrowing journey.” Xavier Navarro Aquino was born and raised in Puerto Rico. His fiction has appeared in Tin House, McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, and Guernica. He has received fellowships and awards from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, MacDowell, and the American Council of Learned Societies. He teaches in the MFA program at the University of Notre Dame.

Xavier Navarro Aquino, author of Velorio.

1. How long did it take you to write Velorio?

I wrote the full draft in five weeks. Then worked through edits for a couple of months before the book went on submission.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Getting started. I resisted writing this book because the aftermath of María was so visceral. After the storm we went through a painful grieving process. The hurricane served to highlight how truly sinister neocolonialism is. The economic despair on the island had been looming since the mid-2000s, but María brought it into the national conversation. Of course now the fear is the short attention span of the media. While many stateside have moved on, María’s aftermath is still evident back home.

Once I came around to writing, the challenge became balancing the polyphonic nature of the novel. The character Urayoán was equal parts liberating and exasperating to write. He is a Caliban figure, filled with paradox and complication. I suspect he will be misread a lot. My hope is readers will slow down and interrogate him at the sentence level. His voice is poetry, even if it’s often predisposed to rants and stream of consciousness. But I’d argue all the characters carry poetry in their unique voices, each one contributing to a chorus of proclamations, agency, and possibilities.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I try to write when I’m not consumed with teaching. So it varies. I used to write very late into the night but that changed now that I adopted two dogs and started teaching at Notre Dame. I’m up early walking pups and lesson planning. By 9 PM I’m exhausted. When I write it’s often all-consuming. Summer break and writing residencies have become a tonic.

4. What are you reading right now?

I just finished Myriam J. A. Chancy’s deft What Storm, What Thunder. Next I’m planning on returning to Eugenides’s The Virgin Suicides, Li’s Where Reasons End, and Nunez’s The Friend as guiding frameworks for my next novel, Two Young Kings. As you’d expect, it’s a novel about two brothers, about trauma, mental health, and suicide.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

To narrow it down to one would be impossible. The two that I’ll mention won’t surprise certain readers. But they should be read more widely in the United States: Dionne Brand and M. NourbeSe Philip are some of the best artists and thinkers working today.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Velorio?

I was surprised with how insistent these characters were. As cheesy as it sounds. Marisol and Camila haunted me leading up to my MacDowell residency. In that isolation everything fell out of me in five intense sleepless weeks. When I finished the draft, I cried.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

It’s not one thing, rather many. Overall my agent, Jin Auh, kept a steady hand of reassurance and faith in the novel. She never wavered in belief even when I did. My editor, Tara Parsons, has an infectious optimism. I’m lucky to have two brilliant advocates for my work.

8. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

Big Five publishers in the United States need to do a better job championing Puerto Rican voices coming out of Puerto Rico, and put money and resources behind narratives that don’t treat Puerto Rican identity, experiences, and events like a periphery experience to the United States. There are 3.4 million American citizens back home living with the complicated history of neocolonization, while also holding onto our own culture and language. It’s time we start working harder on creating access. Translate our work and publicize it widely. Some of what is labeled as “Puerto Rican” in trade publishing favors tired tropes of “Puerto Ricanness”—the same old familiar characters, plots, and themes that are palatable to a white audience. Anything that complicates a white gaze is parsed as strange and foreign. This is comical, considering how much Puerto Rico has contributed to other types of popular culture such as music. I’d love to see publishing stop using our historical events and tragedies as props for appeal. It’s damaging and limiting. There is no absence of Puerto Rican literature, just gross under-translation of work written in Spanish from the island. To that end, works in translation need to become part of the mainstream zeitgeist. Perhaps if that occurs, the United States may see itself as a much smaller part of a larger world filled with unique and imaginative ways of approaching storytelling.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

It starts with my spouse. I’ve apologized countless times that she must endure those terrible first drafts. Then two close friends from grad school. I trust all their judgment.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

It’s not really explicit advice, but it’s certainly stayed with me. “If we don’t tell our stories, someone else will tell them for us.”