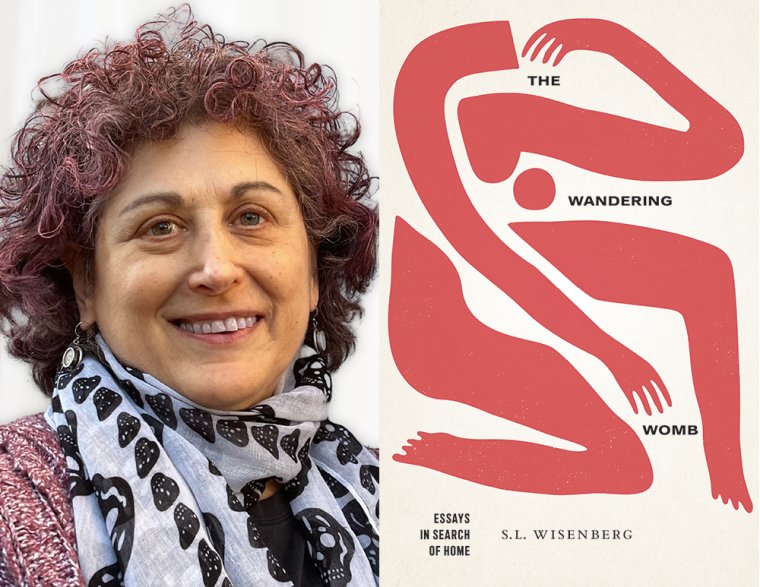

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features S. L. Wisenberg’s The Wandering Womb: Essays in Search of Home, out now from the University of Massachusetts Press. This winner of the Juniper Prize for Creative Nonfiction weaves together a personal history of travel: across the nation, globe, and psychological landscapes formed as much by Wisenberg’s Russian-Jewish heritage as her home state of Texas, her battle with cancer, and encounters with loved ones and strangers along the way. Haunted by the Holocaust, Wisenberg writes of her early childhood fear of Nazis and an adulthood visit to Auschwitz, where she finds herself unexpectedly emotionally vacant. She considers the ironic trajectory of her family history, with ancestors fleeing antisemitic oppression in “Mother Russia” only to settle in the “Black-white” American South, where they assimilated into whiteness: “We were willing to nod at the monuments to the Lost Cause as we stepped up to the courthouse for naturalization,” she writes. “We wanted to live. To thrive.” Wisenberg’s ability to thrive has hinged, in part, on her performance of femininity, and much of the collection considers what it means to be a woman in the world: She contemplates Sigmund Freud’s Studies in Hysteria; partaking in a mikvah, a Jewish ritual bath for women; and aerobics, an endeavor she undertook at thirty because she’d begun to “mourn the condition of my body.” The Southern Review of Books praises The Wandering Womb, saying Wisenberg’s “style is expansive.... This book is at once intellectual, deeply personal, and delightful.” The author of a story collection and two other nonfiction books, Wisenberg is the editor of Another Chicago Magazine and a recipient of fellowships from the Illinois Arts Council, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Massachusetts, among other honors.

S. L. Wisenberg, author of The Wandering Womb: Essays in Search of Home. (Credit: Linc Cohen)

1. How long did it take you to write The Wandering Womb?

Oy. It took thirty years, give or take a few. But I was writing other things in between the essays that are here, including three other books—The Sweetheart Is In; Holocaust Girls: History, Memory & Other Obsessions; and The Adventures of Cancer Bitch—plus book reviews, articles, and a play that should probably be a series of poems.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Because I wrote the essays at various times, each had its own challenges. The difficult thing about putting the book together was twofold. Which essays do I include? And in which order? The most challenging essay in the collection was “Grandmother Russia/Selma,” because it is like a big bag stuffed with a lot of different things: personal history; Russian history; family history; travel to Selma, Alabama; Westerners’ perceptions of Russia; the poem “Babi Yar.” Once everything was in the bag, I had to make the bag shapely and aesthetically pleasing.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write at my desk in my home office on my computer. I write in coffee houses. I write internally when I’m walking by myself in Chicago. I’d love to be consistent, but I’m not—in anything. Alas. When I’m working on a project, I write and revise constantly. Other times, I’ll go a few days without writing. I have become a devotee of the London Writers’ Salon, which offers free Zoom cowriting sessions four times a day, five days a week. I’m usually at the New Zealand morning session, which is 3:00 PM in Chicago, or 4:00 PM, depending on Daylight Savings Time.

4. What are you reading right now?

A bunch of things. Billy Wilder on Assignment: Dispatches from Weimar Berlin and Interwar Vienna, edited by Noah Isenberg and translated by Shelley Frisch. Debra Monroe’s essay collection, It Takes a Worried Woman; it’s a great example of telling instead of showing. The latest The Best American Essays, edited by Alexander Chee. bell hooks’ Bone Black: Memories of Girlhood; it’s made up of vignettes, which I love, and which are always more difficult to write than it looks, and difficult to put together so that they cohere. I’m listening to Grace Talusan’s The Body Papers on Audible. I just read When I Sing, Mountains Dance by Irene Solà and translated from the Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem. It takes a bit of time to get used to it, because at times nonhumans—clouds, chanterelles, a dog—speak. It’s made up of separate stories about the same place, and it turns into a novel. Another novel I just read is Violets by Kyung-sook Shin, translated from the Korean by Anton Hur; it’s very quiet, but devastating.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Grace Paley’s writing voice attaches itself to something in my voice, makes it stronger and more itself. She’s much more connected to Yiddish than I am, and her parents were immigrants, as mine were not. She grew in up the Bronx, and I grew up in Texas, but her rhythms connect to mine. It’s like she’s singing a tune that I can start singing. In my early twenties, reading the early work of Christopher Isherwood and Mary McCarthy showed me that it was okay to write about your insecurities. I can see McCarthy’s influence in one of the earlier essays in the book, “Separate Vacations.” I’ve fallen under her simile-and-metaphor spell. I love, love, love Michelle Cliff’s essay “If I Could Write This in Fire, I Would Write This in Fire.” She moves from passionate to dispassionate, the intimate to the political, all in one essay. This essay taught me that there is a place for rage in an essay, and how to present it. I admire her honesty and try to be as honest and raw as she is in the piece. Eduardo Galeano is historical and lyrical in his The Memory of Fire Trilogy: Genesis, Faces and Masks, and Century of the Wind. Susan Griffin, who is still alive, unlike the previous writers, taught me in her work that you can write in fragments and mix the personal, lyrical, and researched. Whenever there’s a mix like that now, everyone says it’s derivative of Maggie Nelson, but Griffin was doing it before she was. I’m usually slow to read what everyone else is reading.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of The Wandering Womb?

I was surprised how well I wrote when I was younger. I also noticed that I overwrote too.

7. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

It’s in the essay about not sleeping. I remember when I moved from a crib to a bed, and I woke up in the middle of the night; I swear the birds on the mobile over the crib had come alive.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Wandering Womb, what would you say?

I would say it’s okay to write individual pieces, that they will come together in a book eventually. Ever since graduate school, people have been hounding me (and every other writer) to write a Whole Book, whether it’s a novel or a memoir. I’ve finally figured out, after flailing with a novel manuscript for thirty-two years, that I don’t have the kind of brain that can keep track of a novel, though at least some parts of the novel have been published. My writer’s brain picks up little pieces here and there and puts them together. That’s why I love mosaics. I took a weekend course in mosaics at the Magic Gardens in Philadelphia to mark the end of chemo in 2007.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I did a lot of research, online and in libraries. I interviewed people. I traveled and took notes.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Notice everything and write it down. You think you won’t forget it, but you will unless you write it down.