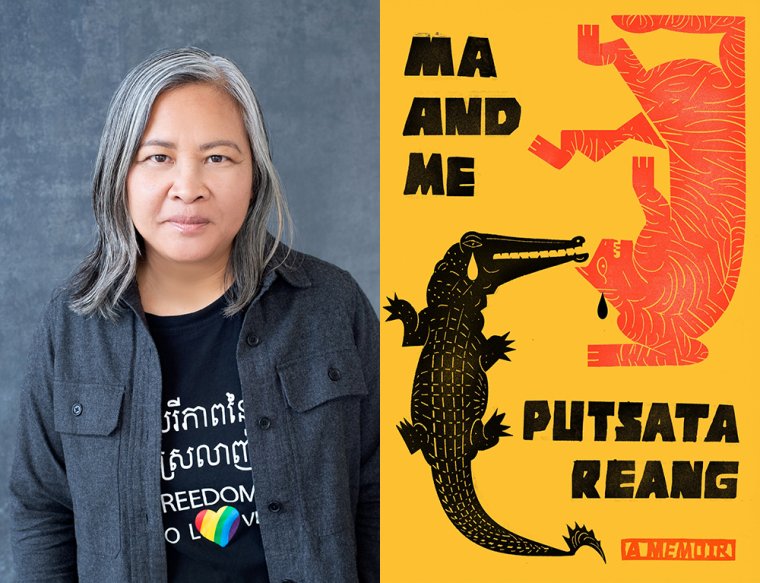

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Putsata Reang, whose debut memoir, Ma and Me, is out today from MCD. A “bridge of story” that Reang builds to close the painful divide between her and her mother, the book doubles as a war-torn family history. Reang was an infant in 1975, when her parents fled Cambodia after the nation’s fall to the Communist Khmer Rouge regime, an event catalyzed by U.S. military intervention during the Vietnam War. Growing up in Oregon with a refugee’s sense of “debt,” Reang narrates her struggle to meet her family’s high expectations—becoming a professional success as a journalist but a disappointment, in her mother’s eyes, as a gay woman. Reang interviews her mother to understand the events that shaped her both before and after the war. She also details her own coming of age as a reporter in the United States and abroad, including in Cambodia, where the joy of connecting with her extended kin is mixed with the sorrow of minimizing her sexuality. Publishers Weekly praised Ma and Me for its “nuanced mediation on love, identity, and belonging. This story of survival radiates with resilience and hope.” Reang’s writing has appeared in the New York Times, Politico, the Guardian, and elsewhere. She has won fellowships from the Alicia Patterson Foundation and Jack Straw Cultural Center and held residencies at Hedgebrook, the Mineral School, and Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts. She teaches memoir writing at the University of Washington School of Professional and Continuing Education.

Putsata Reang, author of Ma and Me. (Credit: Kim Oanh Nguyen)

1. How long did it take you to write Ma and Me?

Technically this was a four-year project, from the time I got my book contract to the time I turned in the last draft. But the truth is, I have been working on this story for the better part of twenty years. Or rather, I have been working around this story. I knew I wanted to write a story about my parents when I moved to Cambodia after receiving an Alicia Patterson Foundation journalism fellowship in 2005. I didn’t plan to write a book that focused on my relationship with my mother. I think that’s where stories sometimes find us, as opposed to the other way around. This story—exploring the disorienting nature of the debt and duty often felt by the children of refugees, with the added complexity of sexual identity—wanted to be told, and I was in a position to tell it.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

There is a profound emotional cost to writing memoir that no one but the memoirist knows. While writing this book, I knew I was engaging in something extremely vulnerable. But that means it was also, in some ways, the bravest thing I have ever done: to not only go backwards in my own life to know myself, my dreams, and motives—and translate that onto the page—but to ask my mother to go backwards too. My mother was often triggered by the questions I asked about her past, about how our family escaped the war in Cambodia, about her youth. When I was writing certain passages and chapters of the book, I was also triggered by being confronted with old wounds from my childhood. There is a third layer of being triggered, which is that now, after the book is done, there’s still more emotional exposure required. Now I have to talk about the book! Holding all the strands of emotion as they came up through different parts of working on the book was the biggest challenge, without a doubt. And now, giving myself the space and freedom to keep feeling those emotions is an even deeper challenge because my upbringing and my impulse has always been to control my emotions. Maybe the lesson here, for me, is to just feel.

3. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Ma and Me?

I had always believed that one of the reasons my mother and I were always butting heads when I was growing up was that we were so different. I was hard to tame as a child. I played rough in the schoolyard and came home with torn and dirty clothes. I was a wreck, especially for a mother who had several children to raise in a new country while learning a new language. Growing up, I had her wrong. I thought she was shy and reserved and didn’t know how to have fun. But that’s not actually true. Looking back with clear eyes, I see that my mother actually loved to have a good time and laugh and joke around, a lot like me. The reason we so often come into conflict is that we are very much alike. She once had dreams of becoming a businesswoman and traveling. I never wanted to be a businesswoman, but the traveling part we absolutely have in common. She has an innate curiosity about the world, just like me. She has wanted to follow her own path without someone telling her what to do, just like me. And in that alikeness, I’ve learned to love her and accept her with a grace I lacked before writing this book.

4. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Ma and Me?

Writing was really only half the battle in wrangling the story of Ma and Me onto the page. The bigger battle had to do with interviewing my mother, which was treacherous territory. Even though my parents were open to sharing their stories with me when I set about formally interviewing them after my father’s heart attack in 2010, there was still both an enormous emotional cost and emotional labor in asking my parents to go backwards and excavate some of the most painful moments of their lives. I often felt sick to my stomach when I knew I had re-triggered my mother, and she would tell me she was too sad to tell me anything more, effectively ending the interview. Of course, there was joy, too, in their lives before the war, and I loved hearing those stories. But the grief was exceedingly deep; there was so much loss. The other part of the equation in pulling this memoir together was the research, which was frustrating as a journalist because I hit so many dead ends. Because of the war and genocide, it was a challenge finding documents and records that would either add to or support my family’s story. As a journalist, my instinct is to always find proof to match source interviews. But in this case, as in the case of many refugees’ stories, the stories live inside the survivors. That’s all we’ve got to go on. They are the only primary source available. That’s where the writer part of me had to accept that there isn’t always an official document to cross-reference for fact-checking stories when it comes to historical and personal narrative.

5. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

My editor once told me: “You don’t have to put anything in this book you don’t want to.” When she said that, I felt so liberated. It felt like an enormous weight was lifted off of me because I had assumed, once I signed on the dotted line of my book contract, that I would have to eviscerate myself to succeed in this project. That’s not the case. There are plenty of hard truths in Ma and Me that were difficult to put down on the page, and then there are other truths that are mine, and mine alone, to keep. It’s a similar idea to a reference I make in the book to my mother having lost a baby when we arrived in the United States, but that is a story that belongs only to my parents. I have no right to it, not even as their daughter. Just as the reader has no right to every little thing in my life, especially if it’s not pertinent to the narrative.

6. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Ma and Me, what would you say?

I would probably ask myself a lot of questions: “Do you really want to do this? And if you do, are you prepared for the dark days that will surely come, when the pain of remembering drives you into a deep hole? Do you have the grit and guts to pull this off? Are you willing to believe in yourself rather than outsource that job to family and friends? Because you are the one who has to stay focused, stay interested and stay dedicated to the story more than anyone else. You are the one who has to show up for yourself.”

7. What are you reading right now?

I’m listening to Silvia Vasquez-Lovado’s memoir, In the Shadow of the Mountain. It is completely breaking my heart, but there are enough crumbs to follow that I think will ultimately lead me to joy in the end. I am also reading Omar el Akkad’s novel, American War, which is aggressively addictive and intense to read at this current moment in our country and in our world.

8. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I used to write every single day when I was working on the memoir, for several hours in the morning and then again later in the evening in a small but exquisitely quiet office shed my wife and I had installed in the backyard during the pandemic. But I’ve slipped on my discipline recently. I’m giving myself a small break from long-form writing. I’m still writing short personal essays, which don’t require the extreme focus of long-form writing. I scratch out words and sentences and sometimes entire parts of stories on the backs of envelopes and notepads and then try to assemble these scattershot pieces into a coherent piece of writing. It’s not a very organized way to write, but it works for me.

9. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Unfortunately, it’s teaching memoir writing, which is terrible because I love my students and I love teaching. But what happens when you are immersed in your students’ personal stories—and those stories slingshot around inside of you—is that they start to crowd out your own story and what you want to say. A friend once told me you can either write or have a life, but it’s difficult to do both at the same time. And I would amend that to say that you can either write or you can teach. I haven’t found a way to make both work at the same time. But I want to continue to teach, and at the same time I desperately want to write.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I don’t know if I have the quote completely correct, but it was Anne Lamott who said something on the order of: “One bad page a day leads to a book.” It’s such great advice for a writer, especially a writer who dreams of being published. Books do not write themselves. And it takes a superhuman commitment to stay in the chair and do the work. And doing the work doesn’t mean sitting down and pulling out a perfect story from thin air. It’s letting yourself write terribly, and laying those awful and embarrassing pages as a foundation to keep getting better. Let yourself have those bad pages, what Anne Lamott calls “shitty first drafts.” No one gets it right the first time, or second time. It took me ten drafts to get to a place of "finished enough" on my memoir. Just keep writing—the good, the bad, the ugly. All of it. One day you’ll look up from your computer and realize you’ve just finished a whole book.