This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Nicolás Medina Mora, whose debut novel, América del Norte, is out today from Soho Press. In this complex tale that crisscrosses centuries, histories, geographies, and literary styles, a privileged, young Mexican writer enrolled in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop finds himself suddenly unmoored by the anti-immigrant politics of the Trump administration, which threatens his ability to remain in the country to complete his degree. At Iowa the twenty-something protagonist finds his peers intellectually and ethically lacking and is confounded by the way they pigeonhole him as a person of color without grasping the sociopolitical nuances of Mexican culture that mark him as a member of the nation’s ruling class. Meanwhile he must navigate the restless politics that are unsettling his native country, including a new president who threatens his father’s livelihood, and family developments that force him to confront his mother’s mortality and his father’s complicated role in the Mexican drug trade. Kirkus praises América del Norte: “A piercing critique of the shallowness of academia and the soufflélike weightlessness of American culture. ... A debut from an author to keep on your radar, assured, darkly funny, and impeccably written.” Born and raised in Mexico City, Nicolás Medina Mora has degrees from Yale University and the University of Iowa. His writing has appeared in n+1, the Nation, and the New York Times. He currently lives in Mexico City, where he is a writer and editor for Revista Nexos.

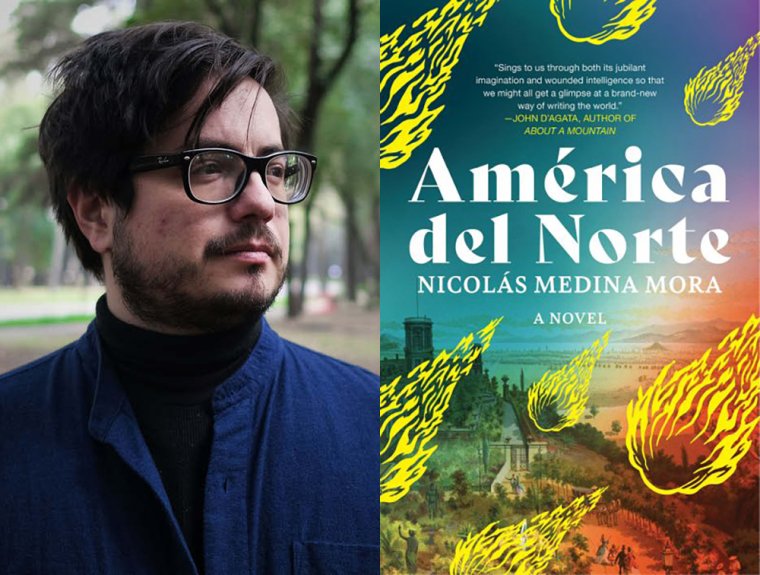

Nicolás Medina Mora, author of América del Norte. (Credit: Soho Press)

1. How long did it take you to write América del Norte?

A long time! The oldest chapters date from 2013; they were originally undergraduate essays. But I began writing the book in earnest only in 2016, when I moved to Iowa City to start an MFA in nonfiction. Back then I thought América del Norte was going to be a long essay about the Mexican elite. But then Donald Trump got elected and my prospects of becoming a permanent resident of the U.S. vanished overnight. After I moved back to Mexico City in 2018, I realized that the story I wanted to tell, which now included the events that led to the end of my time in the U.S., would be better served if I wrote it as fiction. So I suppose you could say that the third and definitive birthday of América del Norte took place in 2020—the year it became a novel.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The most difficult task was devising a structure that could contain the many threads of the novel without losing the reader’s attention. The book considers, among other things: the conquest of Mexico; the rise of Donald Trump; the absurdities of U.S. writing programs; the story of a wealthy Mexican family; the Mexican-American War; the work of a Neo-Baroque painter, an American musicologist, and a Bergsonian filmmaker; the life and times of a fascist ideologue of the Mexican Revolution and of a seventeenth century astrologer; the North American Free Trade Agreement; the Austria-Hungary Empire; the tale of two teenage Indigenous immigrants; etcetera. The editorial guidance of both my agent, Elias Altman, and my editor at Soho Press, Mark Doten, proved essential. They helped me fine-tune the paratactical jump-cuts between threads to ensure that the reader never got lost, that the confusion the book is designed to induce felt like a deliberate choice rather than an involuntary accident. Even more importantly, they pointed out that maybe it would be a good idea to have, you know, something like a plot.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write everywhere: at my study at home, in bed, on flights, while stuck in traffic, at the office of the magazine where I work. I’m a firm believer in Walter Benjamin’s advice to carry a notebook at all times, lest an idea run away from you. But when I have to tackle a big chunk of Serious Writing, as opposed to scribbled notes, I like to clear my schedule for the whole day and wake up at five or six in the morning and work until I run out of steam—or, to be more precise, until the Ritalin I take for my ADHD wears off, which usually happens around five or six in the afternoon.

4. What are you reading right now?

Katherine Rundell’s Super Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne. It’s a sharp and elegant study of the best Anglophone poet of all time, and I can’t recommend it highly enough. I’m also rereading Mauricio Tenorio-Trillo’s Latin America: The Allure and Power of an Idea, an erudite and often quite barbed polemic against the notion that the half-billion people who live in the parts of the western hemisphere that were colonized by the Iberian empires share anything beyond an accident of geography.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

There are too many to name, but the autobiographical side of América del Norte is very much in conversation with Roberto Bolaño, Ben Lerner, and Teju Cole. Its treatment of history owes a great debt to Gabriel García Márquez, W. G. Sebald, and Benjamín Labatut, as well as Walter Benjamin and Louis Althusser. The two chapters that consist of a single long sentence are an attempt to pay homage to the greatest Hispanophone prose writer of our time, Fernanda Melchor, and the metafictional gestures that appear throughout are obviously lifted from Jorge Luis Borges. The main character’s evolving conception of what it means to be at once Mexican and white owes everything to the work of Heriberto Yépez’s Transnational Battle Field, Wendy Trevino’s Brazilian Is Not a Race, and Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life by Barbara J. Fields and Karen E. Fields. I’d always thought that my patron saint was Alfonso Reyes, the great Mexican stylist, but the other day a friend who read my novel pointed out that its structure and concerns are strikingly similar to Carlos Fuentes’s Where the Air Is Clear. I guess that happens with influence: When it’s most intense, it works unconsciously.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of América del Norte?

The capaciousness of the novel form. Until I decided América del Norte would be a work of fiction, I’d mostly written journalism, essays, and criticism. But once I gave myself permission to make shit up, I discovered that fiction can contain nonfiction much more easily than nonfiction can contain fiction. This has nothing to do with fact-checking or veracity—it’s a question of form. My thesis adviser at Iowa, John D’Agata, a writer whom I admire and respect, has made a forceful (and, to my mind, rather compelling) argument for the proposition that essays ought to be liberated from the tyranny of facts. In the end, though, I chose the opposite path: Instead of writing an essay that included fiction, I decided to write fiction that included essays. This is because, at their core, novels aren’t long works of narrative but linguistic containers for the novelist’s obsessions—or, as my old teacher Roberto González Echevarría might say, archives that document their passage through a particular place and time. And the great thing about archives is that they can hold all kinds of documents, all manner of writing. You can put everything and anything you like in them.

7. What is one thing your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

When we had our first conversation after Soho Press decided to make an offer on América del Norte, my editor, Mark Doten, told me he thought the novel should be longer, weirder, and funnier. The most important part of his comment was the last bit: The draft that he’d read already contained moments of humor, but it was for the most part rather self-serious. Mark helped me see that a novel that doesn’t make you laugh out loud every few pages isn’t nearly as good as one that does and that the only way you can get away with seriousness is to balance it with satire, slapstick routines, and self-parody.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started América del Norte, what would you say?

Don’t rush to publish. You’re making a work of art—not enchiladas. A novel worth its salt should take time to write. Otherwise, unless it’s very short and narrowly focused, it will probably be undercooked—or, in my case, something much worse: embarrassing juvenilia.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I did a great deal of research while writing América del Norte. Some of it, such as reading works of scholarship and primary sources about the Mexican-American War or the life of José Vasconcelos, was specifically for the book. But to be honest, while I was writing the novel, I felt that everything I read, saw, and experienced was, however indirectly, research for my project. My diaries, e-mails, and text messages from 2016 through 2018, for instance, became important parts of the book’s archive, as did the notebooks where I’d copied long passages from the books that I’d read since my undergraduate years. The task of the novelist, I think, consists of treating life as a research project.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

Natalia Reyes, a wonderful writer and scholar who was in the fiction workshop at Iowa while I was there, once told me that every bit of dialogue should dramatize a conflict between the characters. It doesn’t have to be anything too big or too loud, but there has to be a clash, a contradiction, a disagreement, or a fight. Otherwise there’s no tension or propulsion, and you’re not writing dialogue but rather transcribing conversations.