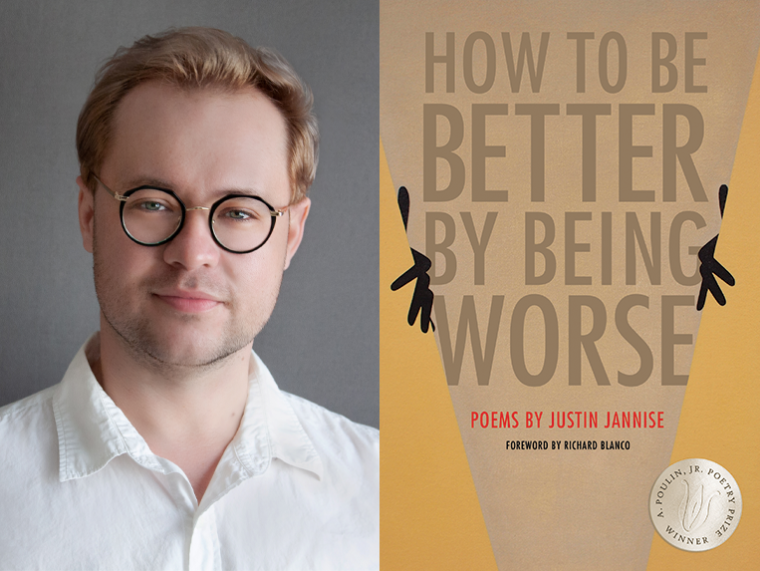

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Justin Jannise, whose debut poetry collection, How to Be Better by Being Worse, is out today from BOA Editions. The poems of How to Be Better by Being Worse are fearless and alive, queer and unapologetically indulgent. In the title poem, Jannise writes: “Be clothed / in scandal. Smear / and smudge and slander yourself // courageous.” Throughout the collection, he heeds his own advice to be daring. He frequently experiments with form—the poem “Flamingosexual” appears as the silhouette of the iconic bird—and tackles issues of family, love, and the self with great emotional honesty. “Justin expertly commands the techniques of his craft to summon up an authentic and undeniable voice that lifts off the page,” writes Richard Blanco, who chose the collection as the winner of the A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize. Justin Jannise received his MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and is currently a PhD candidate in literature and creative writing at the University of Houston. His poems have appeared in numerous publications, including Columbia Journal, Copper Nickel, Hobart, Split Lip, and the Yale Review. He has taught classes for Inprint, Grackle & Grackle, Writespace, and Writers in the Schools.

Justin Jannise, author of How to Be Better by Being Worse.

1. How long did it take you to write How to Be Better by Being Worse?

Seven or eight years. The earliest draft of the oldest poem dates back to 2012, and I was allowed to make some last-minute changes in 2020. There are human beings nearly capable of making a book who were not born when I started writing it.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Everything about writing is a challenge for me, but something that took a really long time to figure out was how best to sequence the poems. I’m aware that many readers will not approach the book from beginning to end, but those who do—I’m almost certain—will enjoy the whole theme park much more than any one thrill ride.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

Before the pandemic I wrote mostly on the go—initially in my head, later on a note-taking app on my phone. Walking is great for poetry. So is driving. Basically, any activity besides sitting and putting down the thoughts that come to mind in the order that they arrive. Shopping. Eavesdropping while eating alone. Juggling or rummaging. Anything that occupies the hands and feet but not the writing brain. I like to know that a line has been turned over a few hundred times before I stop to write it down. I love that scary feeling, once the poem has grown about eight lines solely in my head, that I’m about to receive an important phone call, or witness a crime—something that’ll make me lose the whole thing. Poof! Another masterpiece lost! I love the utter absorption of pulling the vehicle over, or dropping the flaming chainsaws, and as rapidly or discreetly as possible trying to get the important parts down—all over the page sometimes, like a police sketch.

4. What are you reading right now?

Anne Carson’s The Autobiography of Red, in the bathtub. Last fall I read from more than ninety titles for my comprehensive exams, starting with a good chunk of the Bible. I also chose to immerse myself in psychoanalytic theory, which was like learning a foreign language. On my nightstand I have new poetry collections by Erin Belieu, Diane Seuss, Mark Wunderlich, Christopher Kempf, and Natalie Shapero. What I like about poetry is that you can shuttle back and forth between books and it always feels like you’re getting somewhere, but when you stop to look at how much you have left, finishing feels impossible! There are just too many ways to get lost in the woods—in a good way.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I usually find it difficult to tell how widely recognized a writer is. I’ve bounced around enough to know that one person’s junk folder is another’s Treasure Island. If you haven’t read anything by Danez Smith or Ilya Kaminsky, I’m a little afraid of you. Many writers I know have had their first books come out during the pandemic, which feels unfair, but is Benjamin Garcia’s brilliant Thrown in the Throat more or less recognizable for that reason? Are people reading more because they’re going out less? Are they reading more poetry because it resonates more strongly during global catastrophes? Can we all agree that Willa Cather should’ve won a Pulitzer for The Professor’s House and not One of Ours? Is light verse “in”? Is “serious literature” out? How’s the novella doing? And what about all the fantastic work that appears in multi-author volumes—lit mags, anthologies, translations, and so on? What about hybrid genres? Online journals? Zines?! I just learned I’ve been mispronouncing Wisława Szymborska’s name even though she’s one of my all-time favorites. In a poem, Szymborska wrote that maybe two people in a thousand like poetry. That’s less than 0.2 percent! Can we recognize that?

6. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

I wouldn’t say it’s worth taking on a lot of debt, but sure, why not? If your particular brand of genius is so fragile that it can’t withstand a bad teacher’s scrutiny—can’t overcome a hungover classmate’s offhand critique—you think the world of publishing is going to welcome you with open arms? Ha! I know some great writers who opted out of the MFA but still have solid careers and a list of publication credits a mile long. They all live in New York City. They were all born rich.

7. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started How to Be Better by Being Worse, what would you say?

Go to your Google Drive. Create a new folder. Call it “Cover Art Ideas.” Fill it with artwork you’ve seen in galleries, on street corners, at fancy hotel bars—wherever. Keep track of who made it, and when and where you saw it. Include the artist’s or gallery’s contact info if you have it. Only include images you like, but there’s no need to be stingy. A day will come when you will quickly need a TON of good, affordable options and, well, let’s just say that circumstances may prevent you from doing a worldwide tour of all your favorite galleries. There may even be a chance that the only thing you’ll be able to browse is the internet because everything else will be shut down. Have fun!

8. How did you know when the book was finished?

Call me psychic. I just knew.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I trust my friend Christine Kwon, a great writer in her own right, to tell me exactly what she thinks without hesitation or apology.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I don’t know if it’s writing advice per se, but in The Virgin Suicides, Jeffrey Eugenides writes: “All wisdom ends in paradox.” Robert Frost, definitely issuing advice in “The Figure a Poem Makes,” said that a poem “begins in delight and ends in wisdom.” Put those two together and you get that poems end in paradoxes, which might be helpful if you are trying to determine whether or not a poem is finished. I wouldn’t be too literal about it and end every poem with a self-contradictory phrase or something like that, but I do think there’s something sort of final and fulfilling about discovering, say, that a poem’s floor is also its ceiling—as I think I did when I finally arrived at the title of “Poem with Trap Door.”