This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Anne Waldman, whose poetry collection Mesopotopia is out today from Penguin Books. From the mysterious, poetic origins of Mesopotamia to our own contemporary dystopias, Mesopotopia is a radical investigation into the syncretic layers of quantum space and dreamtime. Crafting a palimpsest of language that draws on sacred texts, troubadour dawn songs, pyramid texts, Buddhist mantras, Persian prayers, Druid sorcery, and more, Waldman leverages her passion for performance in a striking meditation on myth and transformation. Eileen Myles writes, to “understand the radiance of the poetry world you have to look at Anne,” and Poetry called Mesopotopia a “powerful and prophetic collection of epic scope and vision.” Anne Waldman is a poet, performer, professor, editor, and cultural activist. She is the author of more than forty-five books, including Gossamurmur (Penguin Books, 2013), Manatee/Humanity (Penguin Books, 2009), and the feminist epic The Iovis Trilogy: Colors in the Mechanism of Concealment (Coffee House Press, 2011), which won the 2012 PEN Center USA Award for Poetry. The recipient of the Poetry Society of America’s Shelley Memorial Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Before Columbus Foundation’s Lifetime Achievement Award, Waldman makes her home in New York City and in Boulder, Colorado, where she is a Distinguished Professor of Writing and Poetics and artistic director of the Summer Writing Program at Naropa University.

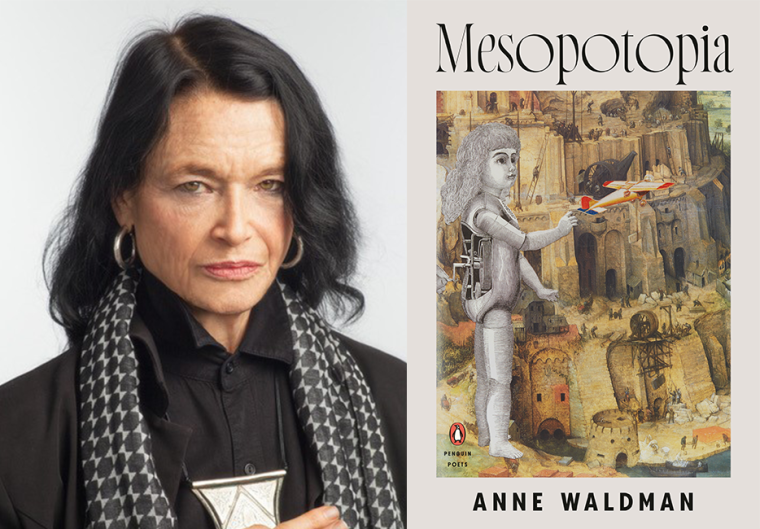

Anne Waldman, author of Mesopotopia. (Credit: Nina Subin)

1. How long did it take you to write Mesopotopia?

It seems like it shape-shifted because I was writing in the middle of and in tandem with serious world chaos, local and everywhere. I’d say at least six years. It definitely started before the plague. I tend to work on several writing projects simultaneously, and the energy is often sustained in an immersive, multitasking poetry way.

For example, one project could be framed by a different sense of time, astral rhythms. And then there’s writing that is closer to what you notice.

My wonderful loyal editor Paul Slovak (now retired) had already secured the contract. It was supposed to be a one-hundred-page manuscript. It more than doubled, and he gave me more time.

I began the assembling process, however, with the seven “staves” or sections when I was finishing the proofs for the memoir-poetry collection Bard, Kinetic (Coffee House Press, 2023).

I felt this deep urgency with the precarity we are all in to say something to reflect on these times, working with the adage “from the cradle to the grave.” From the “birth” of civilization (Mesopotamia) to its decline and death.

The stave is also a staff, a musical notation, and relates to an “enclosure with a fence of wooden posts.” The word conjures a place, an architecture, a support, a walking stick. And much more. In the introduction I call the book “a round of systems.” It is a book of “studying.” I hope people read it slowly.

I already had the title, years back. (In fact, Anne Carson commented that it reminded her of her kitchen sink!) And I knew I wanted the John Ashbery collage for its cover. The windup girl-child-toy-doll tossing a paper plane from the Tower of Babel was a witty depiction of how one feels in these raging times.

It can take a long time reading Saint Augustine, Isaiah, Buddhist texts—and also drawing on literary sources from the past that have embedded in my mind. There is a dip into the work of Hafez (a Persian lyric poet) after a conversation with an Iranian friend. There is a selection of 365 daily phrases with a three-hundred-sixty sixth for good luck, entitled “The Counting: Echolation” that is sourced from various materials: my own journal writing and attention to our current dis-alignment across culture, ethics, economics, and politics. And language. All of this is an engaged practice involving all-night reading.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Having to navigate a lot of material and wanting to incorporate forms out of other cultures and places. The battle cry, the idea of martyrdom, the challenge of elegy, a book of love, too, for what we hold dear. The Buddhist sense of historical karma. And the sins and crimes of our generation.

I wanted the book to radiate and be read as a whole. I consider it an epic in parts, but the sections may stand on their own.

Within it I investigate the times of the chthonic, of sorcery, of Tantric Buddhism, parables, blood moons, nocturne, and elegy. The section in the book “Future Burnt of Leaves” references T. S. Eliot’s “Burnt Norton” and is an elegy for the poet Bernadette Mayer. It was a challenge glossing Eliot for this important poem (I was preparing to participate in the T. S. Eliot Memorial Reading).

It was also challenging seer-ing into the past…. One of my principal obsessions has been war. And origins. I was born at the end of World War II, which my father and so many others served in and witnessed with so much tragic loss of life. Can there be poetry/art after atrocity, after trauma?

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

All the time. At this point I feel especially urgent about holding on to the energy drive of consciousness, in the midst of contending with the dystopia of the late capitalocene, climate warming, and endless war. I want to honor that rich, wild, and generative countercultural history that has informed me and continue to pass on some of the transmissions—listen to the world and have time to mourn poets of the past, keep sanctuary for myself and others. Part of the job is the preparation and ethos around the writing. As Philip Whalen says, “the education continues along.”

Collaborative writing is very important to me, creating room, space, and timeframes for that. I’m currently working on a chapbook entitled Wives of Bath with Zoe Brezsny and Odes to Exile & Tranquility with artwork by Pamela Lawton. Wives of Bath keeps expanding after a few years of adding to it in between day-to-day work. And the film Punch in the Gut of a Star with my partner Ed Bowes and American Catalan poet Emma Gomis. Also, the gorgeous The Velvet Wire (Granary Books, 2024) last fall with the visual artist and poet No Land.

I work at desks in New York City and Boulder, Colorado, and I jot down things when I travel. I usually write late at night when things are quieter. I don’t seem to need as much sleep, and when I’m writing there is some peace in that. I feel synchronized in a way. It’s a steady pulse.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading the James Schuyler biography by Nathan Kernan called A Day Like Any Other: The Life of James Schuyler (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2025). Having known Jimmy, it’s very powerful and poignant and covers things I didn’t know about his early life, and the depth of his struggle with mental illness, and his methods for his exquisite poetry. It’s history and poetry intertwined, and Kernan gives very astute commentary. It’s refreshing to see such a loving and honest investigation receive this kind of attention, the beautifully written story of his life.

I am also reading Love, Joe: The Selected Letters of Joe Brainard (Columbia University Press, 2024) edited by Daniel Kane, Achille Mbembe’s Brutalism (Duke University Press, 2024), The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine (Metropolitan Books, 2020) by Rashid Khalidi, the King James Bible, the writings of James Baldwin, Homer, William Burroughs, Master Dogen, poet Will Alexander, Mahmoud Darwish, and Leslie Scalapino, among many others.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

It’s a vast question, and I’m a pretty steady reader of poetry. As a poet you’re beholden and excited to read writers of other cultures and generations. Poets who speak to the intensity, tenderness, beauty, struggle, and suffering of our time.

Lorenzo Thomas, John Wieners, Clark Coolidge, and Jimmy Schuyler, women poets such as Joyce Mansour, Batool Abu Akleen, Julie Ezelle-Patton, Mirene Arsanios, and Simone White come to mind, among many others.

6. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I had to lay the pages all out and see what the adhesives were between each section, which I call the Seven Staves.

There are different moods or Rasas (Sanskrit for tone or essence) for each grouping. I knew I wanted “Telepathy Across Wounded Galaxies” bookending with “Recital in Walking (Telepathy).”

In the middle of the book (Stave 5) are elegies for Lyn Hejinian, a pyramid text for Cecil Taylor, and an homage to Brice Marden.

I like the idea of action writing, putting text on the floor and playing with arrangement like abstract expressionist painting.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

My longtime editor Paul Slovak was confident with the early draft of Mesopotopia and secured the publishing deal.

It was my other editors Allie Merola and Sonia Gadre who took an interest in the visual aspects of the poetry and the visual decisions on type, stylistic variations, etcetera. That was a little more complex than usual. We had to find a typeface, various ornamental designs, and I wanted a poem entitled “Voyant” to take the form of a fading scroll.

The book had to work as a whole, but it was also separated into sections. I wanted it to feel like everything was a part of this whole, an investigation of the origins of civilization and ongoing war. The interconnected fabric of our consciousness. It was really important that my editors Allie and Sonia supported the visual impact, and that is also to the credit of the designer and production team for supporting the vision as well. My editors also went the extra mile with editing. They were some of the best, most energetic proofreaders—they felt my concern and nervousness around proofreading (when you’re expected to do it all on your own its daunting), and they really rose to the occasion.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Mesopotopia, what would you say?

Go to your studies, go to your imagination, go to your etymological dictionaries, your epic poets for the minds and “makers” of the threads of literary and performative art and ritual.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Mesopotopia?

I’m very involved with the ongoing Naropa experiment, a creative community in Boulder where I designed an MFA and Summer Program called The Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics. We recently had our fiftieth anniversary, and our theme this year was “The Living Thread.” We host guests from all over the world and facilitate classes taught by poetic activists such as Cecilia Vicuna, Cedar Sigo, Eileen Myles, Carolina Ebeid, and CAConrad.

As a guide and a teacher, you’re steeped in the things you care about. Other essential forms of work include editing lectures, most recently New Weathers: Poetics From the Naropa Archive (Nightboat Books, 2022) with Emma Gomis. That’s a very important tome edited from our very exceptional archive.

I recently collaborated with choreographer Douglas Dunn and Dancers; I provided the poetry for his production L’Embarqement pour Cythère at Judson Memorial Church, working with the poems of Rimbaud and Verlaine.

I also was interested in working cinematically with the director Alystyre Julian on the film Outrider, which was released this month. It was fascinating to see the process of arranging the work in relation to itself. It was like working on a very long poem.

These cross-disciplinary projects were all happening in conjunction with the creation of Mesopotopia.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

At an early age my father suggested I write “around” emotions, not let emotion be the whole reason for the writing, how I feel about everything and everyone. “You are your center, but not the center of the world.”

Both Kenneth Koch and Allen Ginsberg said I should keep going with long poems, the heartbeat and musicality of litany, and of layers...and also investigative work.

Studying the world. Remembering the wonderful dreamlike quality of epic, all the transitions and pleasures of orality, a continuous thread.

“And read as much poetry as you can, everywhere, from prisons to castles,” my mother said.

“I learned to read the world as a book,” the poet Milarepa sang.

I remember thinking that Mesopotopia has to work as an oratory creation with music as well. I always envisioned it having peak moments as one would with musical accompaniment.

I’m just an ancient old woman bard by turns chanting, intoning, praying, raging, gesticulating in the mead hall, scribing in the inner temple sanctum, on the streets of the world.