This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Xenobe Purvis, whose debut novel, The Hounding, is out today from Henry Holt. Set in a small village in eighteenth-century England, The Hounding follows the Mansfield girls, five sisters whose neighbors are convinced the girls are turning into dogs. Little Nettlebed is a village suffused with the uncanny, from strange creatures that wash up on the riverbank to ominous ravens flocking to the roofs of people who are about to die. But when the villagers start to hear barking, and one claims to see the Mansfield sisters transform before his eyes, the allegations spark unprecedented fascination and fear. The novel is narrated from the rotating perspectives of five villagers, and the reader soon learns that even if local belief in witchcraft is waning, an aversion to difference is as widespread as ever. Julia Phillips called The Hounding “a debut novel bound to be a cult classic. It’s a tale set centuries ago that throbs with a bloody, living heart…. It’s exquisite.” Xenobe Purvis was born in Tokyo in 1990. She studied English Literature at the University of Oxford, has a master’s degree in creative writing from Royal Holloway, and was part of the London Library’s Emerging Writers Program. She is a writer and literary researcher, with essays published in the Times Literary Supplement, the London Magazine, and elsewhere.

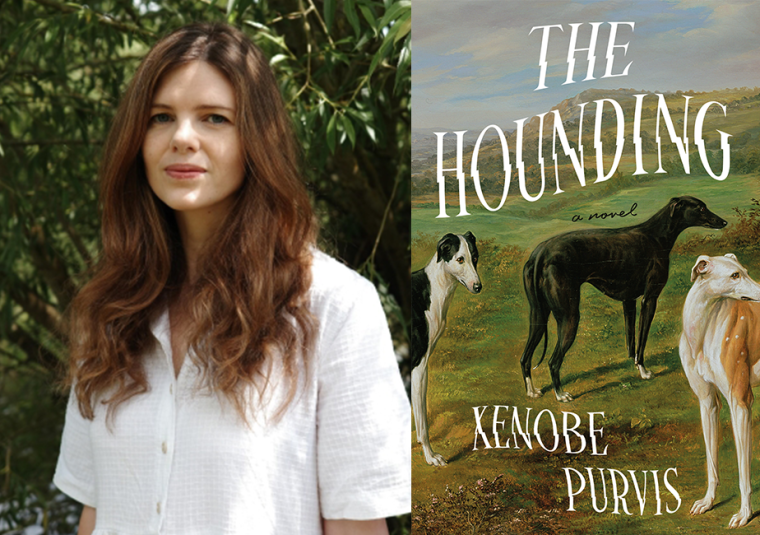

Xenobe Purvis, author of The Hounding. (Credit: Michael Guppy)

1. How long did it take you to write The Hounding?

I researched for many months before I set a single word to paper. The actual writing of the novel was fairly quick—probably a matter of seven or eight months. By the time I came to writing I was very familiar with the material, and it all flowed pretty easily.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The narrative follows the perspectives of five characters with decidedly different personalities and conflicting points of view. One character in particular—a misogynistic ferryman—holds beliefs very far from my own, but I enjoyed the imaginative challenge of trying to inhabit his thoughts.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

If I’m working on something I write every day. I will happily write anywhere: from my bed, at my desk, in the library.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m rereading The Portrait of a Lady by Henry James. Every reread of this wonderful book reveals more; it is a masterpiece.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Tarjei Vesaas is a twentieth century Norwegian writer whose work I first encountered a few years ago. His writing is beautiful. (If, as I was, you’re regrettably unfamiliar with his books, The Ice Palace [Peter Owen Publishers, 1966] is a good place to start. There’s a lovely translation into English by Elizabeth Rokkan.)

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

It used to be finding focus, now it’s finding time.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

It was not precisely what they said, but how they made me feel about the book: Their steadfast faith in it—from very early conversations with my agent, to publication day and beyond—gave me a feeling of security for which I am profoundly grateful.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The Hounding, what would you say?

One grim but exhilarating thing about writing fiction is that it is generally speculative: You never know if your work will find readers. If I could allay that fear by going back in time and assuring my past self that the book would be published, I might have done. But fear can be galvanizing; perhaps the novel would not have been written without it.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of The Hounding?

Reading is so important for writing. And music—great for summoning atmosphere.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Christopher Isherwood was always trying to “get down to the nerve,” an expression borrowed from his friend Francis Bacon. Good writing gets down to the nerve.