On the morning of September 10, 2021, I woke up at 6:50 AM and began my routine like any other school day. I made breakfast for my kids, packed their lunches, hugged them, and sent them on their way. Afterward I poured a cup of coffee and retired to my office to check my messages and my socials. Perusing my Instagram account, I saw that I had several message requests, which was nothing unusual, and I began the business of vetting them. The first of these was from a guy named J.T., or maybe T.J., who wore a trimmed goatee in the style of former major-league slugger Mark McGwire and straddled a muddy ATV in his avatar. I immediately figured him for somebody in one of my sports groups. I was wrong. His message read: “There’s a special place in hell for people like you. I hope you burn.”

This guy might be onto something, I thought. After all, I was far from perfect. I drink too much, I cuss like a longshoreman, and I’ve had countless moments of weakness. But why was his animosity directed at me? I wasn’t going to give it much thought and moved on to the second message, which was from another guy with a goatee: “Don’t ever set foot in Texas, if you value your life. I’ll be waiting for you.” Um, okay. That seemed like a lot of hostility for a Friday morning, but we live in troubled times. I wasn’t planning any trips to Texas, so after my initial momentary unease, I let that one go as well, despite its threatening tone. The third message read: “You probably f*#k your daughter’s, you sick f*#k.” Confused and a bit shaken, I proceeded to my Facebook account, where four more message requests awaited me, including two more threats, along with a vile screed rife with misspellings proclaiming me “a filthy pedo who should rot in hell.”

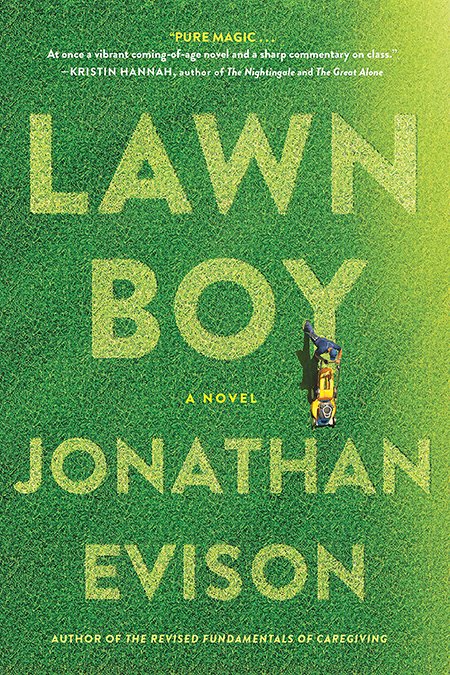

Clearly something very unpleasant was afoot, and Google soon provided the answers. A two-minute search delivered me to headlines from Texas, where I learned that the previous day, at a school board meeting in Leander, a suburb roughly thirty miles north of Austin, a woman named Brandi Burkman had essentially filibustered the proceedings to protest the inclusion of Lawn Boy, my 2018 adult novel, in the high school library. She had arrived with posterboard props, including one she made her teenage son hold up for all to see. It read: “Pedophil” [sic].

Burkman, talking over all who attempted to dissuade her, then proceeded to read aloud a paragraph from Lawn Boy, completely out of context, before labeling the author a pedophile for “promoting” sex between fourth graders, which was surely not my intent. Somebody attending the meeting shot a video of these bizarre proceedings and posted it on TikTok, where it went viral in a matter of hours. That’s all it took to trigger a loosely organized campaign of threats, cyberattacks, and doxing that immediately followed and still dog me almost a year later.

Let me be clear: There is no pedophilia in my novel. The sex act alluded to in the passage in question is an innocent experimentation between two eleven-year-old boys. The scene, which is revisited through dialogue by the adult narrator, is intentionally couched in coarse language for the salient purpose on the narrator’s part of shocking his homophobic best friend as he finally comes out to him. By no means is the act itself portrayed graphically; indeed, nowhere among Lawn Boy’s nearly three-hundred pages is a sex act graphically portrayed. Either Burkman was suffering from a distinct deficit in reading comprehension or she was willfully misrepresenting my work and my person. Conflating sexual experimentation between two boys with pedophilia is, by definition, misinformed. But in the coming weeks Brandi Burkman and her fellow inquisitors doubled down on perpetuating this false information, publicly smearing Lawn Boy at every opportunity, including dozens of scathing Amazon and Goodreads reviews claiming its author to be a pedophile, a sicko, and a groomer of young boys, not to mention numerous more personal threats to my safety and the safety of my family, along with some hate letters depicting sex acts with my three children far more graphic than anything portrayed in Lawn Boy. And I was the pedophile? Clearly none of these people had bothered to read the book; they were simply triggered by Burkman’s misrepresentation of its author.

Welcome to life in the post-truth era.

![]()

Several weeks later, after a similar controversy in a Virginia school district, Republican gubernatorial candidate Glenn Youngkin decided to take this misinformation and run with it for his own political gain, not only perpetuating falsehoods about Lawn Boy and other challenged books, but also smearing librarians and educators in Virginia and elsewhere. Youngkin shrewdly reframed the book-banning controversy in an attempt to rile up a moribund conservative voting base for the upcoming midterm election. His argument ran something like this: These woke educators and librarians are trying to indoctrinate our children with homosexuality and filth and keep your voice as parents out of the classroom! It was a naked display of pure political posturing on Youngkin’s part, and largely successful, though entirely false. Needless to say, educators were doing nothing of the sort. But facts are apparently immaterial in the post-truth era.

Youngkin’s rhetoric inspired a fresh wave of hate mail and slanderous reviews from people who once again clearly hadn’t bothered reading my book. And I was by no means the lone target of their vitriol. Authors, librarians, educators, and school board members everywhere were now under attack from a sanctimonious army of would-be censors. The situation was nothing less than a study in disinformation. Soon Lawn Boy was being conflated with Gary Paulsen’s 2007 children’s book of the same title, inspiring inquisitors to claim that the author was grooming children for indecent purposes. None of these protesters read Paulsen’s book, either. There’s no sex in it at all. It’s about a kid who mows lawns for money, and it is perfectly appropriate for middle-grade readers, a demographic my Lawn Boy, an adult novel, was never intended to reach. And yet Paulsen, too, in what would prove to be the waning weeks of his life—he died last October at age eighty-two—was unwittingly vilified as a pedophile and a groomer because these detractors, who were targeting the wrong book and the wrong author for offenses neither book nor author was guilty of, were simply not interested in facts. They apparently just needed some fresh wood to feed the flames of their outrage.

When Lawn Boy became the subject of considerable media coverage, both regionally and nationally, the bulk of which debunked the myth of pedophilic subject matter in no uncertain terms, the book banners conveniently disregarded these rectifications.

Still, not one of these would-be book banners or gatekeepers had bothered to rescind, alter, or in any way amend the misinformation they continued to propagate. Not only did they refuse to read the book in question, but they couldn’t even cite the right book. Their efforts to ban Lawn Boy soon expanded beyond the realm of school libraries to include retail stores, such as one Barnes & Noble in Florida that temporarily pulled the book due to pressure from a small group of outraged parents. Meanwhile, students in Virginia and elsewhere staged protests in support of Lawn Boy and other challenged titles, buying the books in bulk and handing them out free of charge. Thus, despite my being miscast as a groomer of children amid the personal threats I received, the backlash was enormous. Each week I received dozens of messages of support from educators, students, librarians, and school board members alike. I prepared statements presented by students at a half dozen school board meetings. The ACLU included the defense of Lawn Boy in a lawsuit filed earlier this year in Missouri. I’ve done over a hundred interviews specifically regarding the banning of Lawn Boy. The boost in sales from this controversy has resulted in three additional printings of the novel since September 2021. In fact, the book’s publisher, Algonquin, has had trouble keeping up with demand. At one point between print runs, there wasn’t a print copy to be had on Amazon for under fifty dollars. The fact is, these widespread efforts to challenge and ban Lawn Boy have only driven sales and raised awareness of the book. So, what are the book banners actually accomplishing?

Whatever their true motive may be, beyond making noise, there is a recklessness to this willful ignorance that I find deeply unsettling, and it leads me to what I believe to be the real reason people want to ban books, in particular my Lawn Boy, or Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer (Oni Press, 2019), or George M. Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue: A Memoir-Manifesto (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020), the three most banned or challenged books in America, according to the list recently compiled by the American Library Association (ALA). The challengers submit that young minds should be protected from such filth, and yet many of these same parents don’t hesitate to give their kids smartphones and grant them unchecked access to all manner of adult and pornographic content. So why not ban the internet? What are their parents really attempting to shelter them from? Because the graphic subject matter argument simply doesn’t hold water. Sexual experimentation has long been a staple of young adult and even middle-grade fiction, and yet until relatively recently it was largely binary in its presentation. Funny how the top three challenged books in America feature LGBTQIA+ themes. Funny how nearly every single book on the ALA’s Most Challenged List features nonwhite or nonbinary characters. Hmm, could there be a pattern here?

It certainly seems as though these moral crusaders want to expunge these books from libraries not because they are pornographic in nature, but because these books threaten some of their fundamental beliefs, such as the belief that white, cisgender, Judeo-Christian lives are somehow more important, and more central to the American experience, than other lives. Sound familiar? Wasn’t this the same crowd chanting “All Lives Matter” throughout the Black Lives Matter protests? They know they are losing the culture wars and they’re scared. And so, like cornered animals, they lash out at that which threatens them. It sounds like a losing proposition, and mathematically it ought to be, except we are dealing with a resourceful, highly motivated, and very vocal minority determined to insinuate themselves in policy-making at every level of governance. And to this end, those who dare to call themselves patriots are intent on launching a campaign of wholesale censorship that flies in the face of the First Amendment. Why? Could it be because, to them, America was never about liberty and justice for all but rather about maintaining the status quo? What patriot would deny representation to those very sectors of the population most in need of advocacy: young, nonwhite, nonbinary people looking for their place within a larger culture that never seems to give them a break. It seems obvious on the surface that these self-appointed gatekeepers don’t want “those people” to have voices, and by “those people” I mean Black and brown and gay and trans people—in short, anyone who doesn’t fit neatly into their white, straight, Christian ideal of America, a country largely built on the backs of nonwhite, non-Christian people, and a country traditionally celebrated for its pluralism.

![]()

The protagonist of Lawn Boy, Mike Munoz, a young working-class Chicano who hangs out in the library while his mom works late, wonders: “Where were the books about me?” Well, if the book banners have their way, a new generation of readers will soon be asking the same question as Mike.

What I still fail to grasp about the whole book-banning controversy is why such a large sector of conservatives want to silence these voices. What are they so afraid of? It seems clear that they want the Mike Munozes of the world to continue to exist on the margins of society, for fear that they themselves will be “replaced” by the people who never got a fair shake in the first place—as if granting marginalized people a voice or empowering them with due representation in any way diminishes their own quality of life. Aren’t these the same self-proclaimed bootstrappers who would deny others forgiveness of their student loans because “it’s not fair”? Talk to Mike Munoz about fair. Talk to just about any nonwhite, nonbinary, non-Christian poor person in America and see if they’ve enjoyed the same entitlements as those white, straight Christians so eager to hoard them. Not only would they deny the Mike Munozes of the world these entitlements, but they would also deny them the comfort of belonging, of finding among the stacks of library books voices who spoke to them directly, who bolstered their resolve and replenished their spirit and renewed their faith in the world. The books that told them they were not alone, that there were other people like them, struggling and persevering. And that they had a place in America.

All Mike Munoz wanted was “a book that grabbed me by the collar and implored me to conquer my fears and embrace the unknown. I wanted a novel that acted as a clarion call for the disenfranchised of the world.” Is that such a big ask from an America that was all but built on grand promises? I don’t think so. Chances are, you don’t either. And yet book banners would seek to deny Mike this wish, because they’d rather keep Mike just where he is: disillusioned, disenfranchised, impoverished, and preferably in the closet. And the best way to do that is to not let him tell his story.

Jonathan Evison is the New York Times best-selling author of seven novels, most recently Small World (Dutton, 2022). He lives in Washington State.