After the failure of Zoo Press's fiction contests in 2004, many figured the worst was over for the independent publisher founded by Neil Azevedo in Omaha three years earlier. After all, the press may have proved unsuccessful at administering the Award for Short Fiction and the Angela Marie Ortiz Award for the Novel—neither of which was ever given to a single fiction writer—but at least Zoo Press was still publishing poetry. And its poetry awards—the Kenyon Review Prize and the Paris Review Prize, each requiring a twenty-five-dollar entry fee and offering a cash prize plus publication—appeared to be doing well.

David Baker, the Kenyon Review's poetry editor, thought so too. "It seemed like a great thing," he says of the first-book award his magazine cosponsored. Zoo Press screened the contest submissions and sent a "couple dozen" of the manuscripts to Baker, who selected a winner. (Baker did not receive a fee for judging.) The prize money, thirty-five hundred dollars as an advance against royalties, was paid to the winner by Zoo Press. The Paris Review also agreed to lend its name to Zoo Press for a poetry book prize, as did Parnassus for a prize in poetry criticism. The partnership between Zoo Press and the Kenyon Review, which began in 2001, was a success for the first two years. Two books—Beth Ann Fennelly's Open House, the winner of the 2001 Kenyon Review Prize, and Christopher Cessac's Republic Sublime, the 2002 prizewinner—were published. "The first books were gorgeous, and good," says Baker. "I've been proud of every one of [our] picks."

Then, late in 2004, as news of Zoo Press's failed fiction program spread, things started to go awry. "Neil grew more and more difficult to reach," says Randall Mann, whose book was published by the press earlier that year. "By the fall of 2004, he had fallen off the map." Phone calls and e-mails, to the Zoo Press offices as well as to Azevedo's home, were unanswered. "I'd heard nothing from them," says C. Dale Young, whose book was supposed to be published by Zoo Press in the spring of 2005, "and I became nervous."

Zoo Press's distributor, the University of Nebraska Press (UNP), in Lincoln, was also concerned. In the fall of 2004, none of the five books Zoo Press was slated to publish that season had appeared, says UNP director Gary Dunham, "and we couldn't get ahold of Neil." As it turned out, Dunham says, all five "were at the printer—but the printer refused to release them because Neil hadn't paid them." Finally, UNP intervened and paid for the books to be printed. "Neil told me, 'You make this onetime payment, and we're going to be fine,'" recalls Dunham. But those five titles—No Planets Strike by Josh Bell, Thirty Years War: Love Poems by Patricia Ferrell, Mother Quiet by Martha Rhodes, The Swan Song of Vaudeville by Alan Ziegler, and Techne's Clearinghouse by John Foy—all of which, with the help of UNP, finally came out in early 2005, were the last Zoo Press published.

Baker, too, was becoming increasingly frustrated. His pick for the 2004 Kenyon Review Prize, Priscilla Sneff, had not received her prize money; her book, O Woolly City, remained unpublished; and Azevedo wasn't responding to multiple e-mails, phone calls, and letters. Baker sent Azevedo "a kind of last-ditch ultimatum" in the fall of 2005. "I just said, 'Look, call me this week. If you don't get ahold of me now, we're just gonna have to pull out, we're gonna have to dissolve the relationship between Zoo and Kenyon.' It had gone on too long. And I still heard nothing." So Baker sent a letter to Azevedo ending the relationship.

Weeks later, however, the Zoo Press Web site had not been updated; it still featured an old announcement soliciting submissions for the 2005 Kenyon Review Prize, with an extended deadline. Baker says poets began asking him about their manuscripts, but he "knew nothing about the submissions for the '05 contest." In fact, no manuscripts submitted in 2005 were ever passed along to the Kenyon Review. Zoo Press received around two hundred submissions for the contest. No winner was chosen, and no entry fees were refunded.

It became clear to Baker that a more public notice of the situation needed to be made. So, in late January 2006, he took the additional step of publishing an open letter on the Kenyon Review Web site, informing readers of his decision and the uncertain fate of Sneff's O Woolly City. "Her book is still not available," he wrote, "nor is it in production. She has never received the substantial prize money. She has heard nothing from Zoo Press for a year." And neither, Baker wrote, had he. (After the letter was posted, Tupelo Press agreed to publish O Woolly City.)

Sneff wasn't the only Zoo Press prizewinner left in the lurch. John Drury, the winner of the 2004 Paris Review Prize, never received his five-thousand-dollar prize money, and his book has not been published. Whereas Sneff signed a contract but never got a copy back from Zoo Press, Drury never received a contract in the first place. As with the Kenyon Review Prize, no winner was chosen for the 2005 Paris Review Prize, and no entry fees were refunded. Azevedo says he used the fees from both contests to pay the press's "operating expenses."

Like Baker, Philip Gourevitch, editor of the Paris Review, attempted to sever ties with Zoo Press. Gourevitch says that after speaking with Azevedo in October 2005—unlike Baker, Gourevitch was able to reach Azevedo on the phone—he considered his magazine's relationship with Zoo Press over, but there was no acknowledgment of that fact on the Zoo Press Web site. The Paris Review subsequently "formally and legally" ended its relationship with Zoo Press, and also posted an open letter on its Web site to that effect.

In addition to Sneff's and Drury's books, there are three other titles under contract with Zoo Press that have yet to be published. And four other authors—Christian Wiman, Rigoberto González, David Barber, and C. Dale Young—have extricated themselves from contracts with Zoo Press, and their books have been picked up by other presses. The winners of the 2003 Paris Review Prize and the 2003 Kenyon Review Prize (Patricia Ferrell and Randall Mann, respectively) had their books published, but never received their prize money.

Other authors whose books have been published by Zoo Press report problems going back even further—advances never paid, statements never received. No Parnassus Prize in Poetry Criticism was ever awarded. (Only four submissions were received, Azevedo says, and the submission fees were returned.) Although the full extent of Zoo Press's financial troubles may never be publicly known, it is on record that the company was dissolved by the State of Nebraska for nonpayment of taxes in April 2002, but was reinstated in October of that same year. (Zoo Press was incorporated in Nebraska in 2001 as a for-profit company.)

The University of Nebraska Press has also "severed all ties" with Zoo Press, says Dunham, leaving the press without a distributor. All Zoo Press titles are still, technically, in print, but the actual books—"several thousand" of them, according to Dunham—remain in UNP's warehouse, for which UNP is charging Zoo Press a storage fee. It has been rumored that UNP would have to pulp the books, but Dunham says that they will not do that. "We would never mistreat the books," he says.

How could a small press that was able to attract talented poets and establish partnerships with esteemed literary magazines like the Kenyon Review and the Paris Review collapse like this? What went wrong? In a letter to all Zoo Press authors sent in April 2005, Azevedo apologized for his "silence" and "disappearance" and for all the press's problems at the time. His father had passed away the previous month, he explained, leaving behind "a small psychotherapy clinic that had financial issues that were.are.serious and complicated."

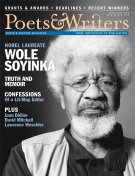

In addition to his personal difficulties, Azevedo wrote, Zoo Press had lately been "fraught with challenges." He wrote that personnel changes at UNP had delayed the press's publishing schedule—a claim that Dunham says is "absurd." There had also been staff changes at Zoo Press; the press's associate editor had quit, and the editorial assistant wasn't "entirely successful," Azevedo wrote. Additionally, Zoo Press's old address was published in the listing for the Kenyon Review Prize in the Grants & Awards section of the March/April 2005 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine, which resulted, Azevedo wrote, in "the lion's share of our operating budget [being] in limbo as we only received about a third of what we normally get for submissions." While Poets & Writers Magazine regrets the error, Azevedo had already "fallen off the map," as Mann put it, before the listing was published.

In a recent telephone conversation, Azevedo admitted that, historically, more than half of Zoo Press's annual budget was derived from entry fees; the remainder came from book sales. Azevedo insists, however, that the press never "generate[d] the kind of income that you get rich on—or even get by on. I really want to bust the myth that somehow I'm sitting here in Omaha on a gold throne that's been paid for by the contest entries," he says. "It's so not like that." Zoo Press paid him an "insignificant" salary, Azevedo says. "I probably made like two dollars an hour." By 2005, he was putting his own money into the press—going, he says, "into the toilet" financially. "For everybody who felt like they lost something, I certainly lost more," says Azevedo, who claims he lost "tens of thousands of dollars—personally," in both credit card debt and personal savings. As for the lack of communication cited by Baker and several Zoo Press authors, Azevedo says it was a "routine silence" that "just extended and extended."

While Azevedo won't confirm that the press will indeed close, "Zoo," he says, "is likely closing up shop." Azevedo has been holding out hope for the press's survival. A colleague of his in Omaha, he says, had considered the possibility of starting a nonprofit company that would then buy Zoo Press outright, retaining Azevedo solely in an advisory capacity; in late February, however, that prospect fell through completely. Now Azevedo is trying to find another publisher to acquire Zoo Press's backlist (the contracts and the physical books in UNP's warehouse), as well as the books in contractual limbo. He hopes that the twenty-nine titles that the press has published, including a book of poetry by the lead singer of Wilco, Jeff Tweedy, will be an appealing proposition for someone. "What's saddest to me," Azevedo says, "is that in the event that I [became] incapacitated—which, I guess, I kinda did—nobody really cared."

As it turns out, plenty of people cared and continue to care—not the least of whom are those who were associated with Zoo Press. "It's a sad story, especially because he seems to have tried to do something that a lot of people have wanted to do with poetry," says Gourevitch. "I really regret that people have lost money, and hope, and have been misled in an enterprise that used the Paris Review's good name. And also, most of all, that the winners have been kept hanging in a completely unacceptable fashion—and they've ultimately been stiffed."

Martha Rhodes, a poet, Zoo Press author, and director of Four Way Books, says that many authors have wanted to help—but that even offers of assistance were met with silence. "If a press is in trouble, and a press has to go under, do it with dignity," she says. Baker agrees. "Independent presses are born and perish all the time," he says. "But there's a right way and a wrong way to do that."

"I send forth the most sincere apology that I can—with the caveat that I really don't know how I could have done anything different," says Azevedo, whose own future, without Zoo Press, is uncertain. During the past year he has been teaching as an adjunct professor at the University of Nebraska, Omaha, but "it doesn't pay enough." After finding a home for the remaining Zoo Press books, Azevedo says, "I guess I'll have to go get a job."

Thomas Hopkins, a recent graduate of NYU’s creative writing program, lives in Brooklyn.