Charles Theonia’s latest book looks nothing like a book. Instead it is a collection of twenty-one tiny glass bottles, each one with a poem inside. When Theonia, a transgender writer who goes by the pronouns they and them, was beginning hormone replacement therapy, they rubbed a saw-palmetto tincture into their scalp to prevent hair loss; while they sat motionless under the dripping extract, they wrote poems about hormones, community, and existential questions of identity. Saw Palmettos, published by Container in 2018, is a series of tincture vials arranged on a wooden stand, each clear bottle holding a poem printed on thin vellum. White oak timbers were milled, joined, cut to size, smoothed, and polished by hand by to create the stand. Twenty-one shallow wells were drilled into the wood, and each vial is etched with the number of the poem enclosed. Jenni B. Baker and Douglas Luman, the founders of Container, did all the work by hand.

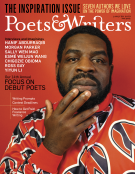

Charles Theonia’s Saw Palmettos is a collection of poems in glass bottles. (Credit: Container)

Baker and Luman founded Container, a small press dedicated to creating books that “aren’t, in a quotidian sense, books at all” in February 2017. In addition to Theonia’s bottles, the press’s catalog includes work composed of origami gemstones, Rolodexes, lunch boxes, a doctored Operation game board, and View-Masters with custom reels. When readers insert a reel into the View-Master, instead of seeing a panorama postcard of Saint Louis or Niagara Falls, they find a ghost of a woman floating above a sentence or a poem fragment snared in a collage.

In the decade before they founded Container, Baker and Luman, who are both poets, became increasingly drawn to maker culture. Print-on-demand services had made self-publishing more readily accessible, and with better technology and the rise of maker spaces, artists could more easily produce their own works. The pair realized that the codex—that is, printed pieces of paper stacked and bound together, a book in the most traditional sense—was not the only possible form a text could take. Taking inspiration from books by artists such as Jen Bervin, Jill Magid, and Julie Chen, they decided to turn traditional publishing on its head.

Container isn’t meant to replace traditional books, the founders say, but rather to expand the understanding of what it means to be a book. “We coexist with traditional book publishing completely amicably,” Luman says. “We think of the forms that Container takes on as the appropriate manifestation of that project. These projects could not be conceived of as codex books.” The publishers team with authors to create works in two ways: by building objects based on proposals (the first pitch Baker and Luman accepted was a series of poems published as a mineral collection) or by giving authors objects that they can build into pieces themselves. Container produces many of its books in Open Works, a maker space in Baltimore that provides access to a wide variety of materials and tools, as well as master classes on how to use various media. One reason Baker and Luman were drawn to Theonia’s project was that it would give them a chance to take advantage of the Open Works woodworking studio. Several authors have chosen to create their own pieces: Poet sam sax, for instance, gilded a Scrabble set, and poet CAConrad turned a metal Gremlins lunch box into a “portable crystal grid.” When Baker and Luman handed poet Lillian-Yvonne Bertram a vintage Rolodex, asking her to fill the cards with anything, Bertram was daunted at first: “Oh Lord,” she thought, “I have three months to do this, and I don’t so much as own a colored pencil.” But Bertram soon found that the constraint freed her to try things she wouldn’t normally attempt. “It completely changed my practice,” Bertram says. “It added something to it, or exposed a realm that maybe had been lying dormant.” Bertram’s Rolodex engaged the diaries and notebooks of artist Paul Klee; she cast several of the cards in wax and hand-stamped quotes and phrases letter by letter. She became obsessed with the physicality of the work. “What do I have to do to my body to make this text happen?” Bertram says she found herself wondering. “What’s the physical process?”

The project inspired Bertram so much that she created a class at the University of Massachusetts in Boston, where she teaches in the MFA program, based on the experience. “Beyond Genre: Not Otherwise Specified (NOS) or, the Shape of Content” invites students to explore the intersection between art and poetry. She and the Container team work together on the class’s final project, in which students make art books that become part of Container’s catalog.

Looking forward, Baker and Luman are exploring other classes and collaborations to help encourage people to think outside the book. They hope to devise interesting ways to digitize their creations and to explore partnerships with traditional publishers to create objects for previously published books. “We’re not a substitute for books,” Luman says. “We think there’s room for conceptual thinking to become a skill we can help others cultivate.”

Adrienne Raphel is the author of the poetry collections What Was It For (Rescue Press, 2017) and But What Will We Do (Seattle Review, 2016). Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, the Paris Review Daily, Lana Turner, Prelude, and elsewhere.