In August 2013, P&W-funded writer Bushra Rehman released--eleven weeks after the birth of her daughter--Corona (Sibling Rivalry Press), a dark comedy about being South Asian in the United States. Rehman has been supported by the Readings/Workshops Program for her writing workshop "Two Truths and a Lie: Writing Autobiographical Fiction." Her novel, Corona, was featured in Poets & Writers Best Debut Summer Fiction.

I just gave birth to a book and a baby. It turns out that in the time it took from the acceptance of my manuscript to the moment of its publication, I could create a small human being in my body. I’d never thought I’d give birth, but I’d dreamed of my book launch like other women (at least according to bad television) dream of their wedding days. I used to think motherhood would make it impossible to write. I didn’t know my daughter would change my entire approach to the writing life.

To Become a Better Writer, Become a Marathon Runner or Get Knocked Up

In What I Talk About When I Talk about Running, Haruki Murakami makes a case for staying in optimum health. He says the body needs to be cared for like any essential in a writer’s toolbox. I finally understood what he meant. Although I’d spent almost a decade working on my novel, in the light of my vitamin-pumped, fruit-and-vegetable-filled, caffeine-alcohol-and-smoke-free body, I suddenly saw structural flaws I was able to fix in the knick of time. It was as if my daughter was the messenger carrying the results of the soil test in Pisa, reaching the architects before the first piece of marble was laid.

Like Babies Through the Hourglass, So Are the Days of Our Lives

A newborn will show the passage of time like nobody’s business. Did she just have a growth spurt and burst out of that onesie while I was changing her diaper? Yes, she did! I know if I want to finish my next book, I better get to it before I’m attending her graduation wearing Depends. (This last detail might only apply to older parents like me.) I no longer make excuses or wait for long stretches of time to work. Whether it is at 4 a.m. or 10 p.m., if I have five minutes, I write.

Take the Red Pill and Leave the Matrix

The first time I heard Hanif Kureishi speak, an audience member asked him how he found the discipline to sit in a room every day and work. His answer was: “How do you leave the room?” I know what he meant. I too had become chained to my laptop. With my daughter, I had to unplug. At first I was resistant… Must check Facebook... But then I began to wonder: What is she looking at? Oh, wow, it’s a... cloud… it’s a geometrically surreal pattern on my pillowcase that’s pretty trippy. Following her line of vision, I was amazed by each tiny miracle strewn throughout my world and was reminded it was this poetic eye that had brought me to writing in the first place.

I have a body. My baby has a body, and guess what, everyone in the world has a body, including my characters.

Giving birth forced me to realize I wasn’t just a floating head in space. Not only did I experience a form of pain that burned away a layer of my soul, I suddenly saw the world of my characters as a world filled with fleshy beings. I could see their bodies like I could see my baby’s goofy-sweet smile and light-filled eyes.

Yes, my baby is the best audience in the world. She laughs at everything I read, but before you run out and get pregnant, you should know taking care of a newborn is hard, harder than you would ever believe! You don’t have to be pregnant or give birth to benefit from these thoughts. Try it for nine months: Live as if you were growing a human being inside you, unplug, re-enter your physical body and world. See what it does for your writing. If you do it without a newborn, you might even get some sleep.

Photo: Bushra Rehman. Credit: Jaishri Abichandani

Support for Readings/Workshops in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Louis & Anne Abrons Foundation, the Axe-Houghton Foundation, The Cowles Charitable Trust, the Abbey K. Starr Charitable Trust, and the Friends of Poets & Writers.

To apply for the grants, writers may submit four copies of a short story, an essay, or a novel excerpt of up to ten pages (or between 1,000 and 2,500 words), along with the required entry form and a $10 entry fee, by October 20. Submissions are accepted by postal mail only. Visit the website for complete guidelines.

To apply for the grants, writers may submit four copies of a short story, an essay, or a novel excerpt of up to ten pages (or between 1,000 and 2,500 words), along with the required entry form and a $10 entry fee, by October 20. Submissions are accepted by postal mail only. Visit the website for complete guidelines.

The first question people always ask me about my novel Corona is if it’s true. Yes, like me the character is a Pakistani who grew up in Corona, Queens, worked as a Puritan in a living history museum, and hitchhiked up and down the East Coast in her twenties, but to say Razia’s life is my life is somehow still not true. Razia is Bushra 2.0: stronger, faster, smarter, quicker. She says all the things I wish I’d said. She doesn’t take as much bull crap. She’s me without the endless hours of agonizing, worrying, and being depressed. Also, most of the events in the book didn’t really happen.

The first question people always ask me about my novel Corona is if it’s true. Yes, like me the character is a Pakistani who grew up in Corona, Queens, worked as a Puritan in a living history museum, and hitchhiked up and down the East Coast in her twenties, but to say Razia’s life is my life is somehow still not true. Razia is Bushra 2.0: stronger, faster, smarter, quicker. She says all the things I wish I’d said. She doesn’t take as much bull crap. She’s me without the endless hours of agonizing, worrying, and being depressed. Also, most of the events in the book didn’t really happen.

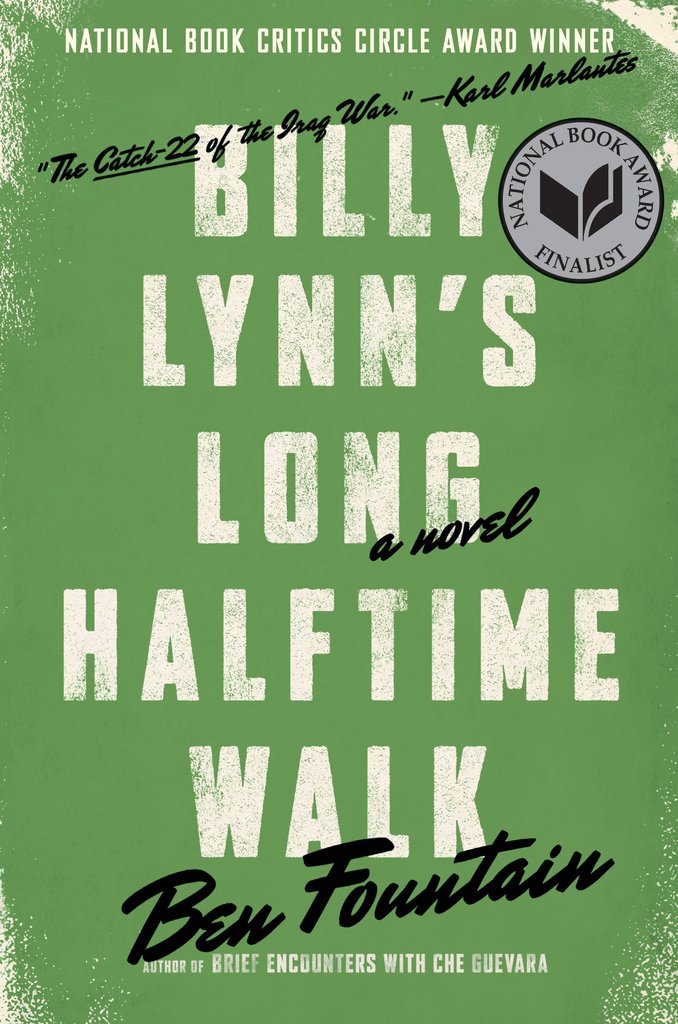

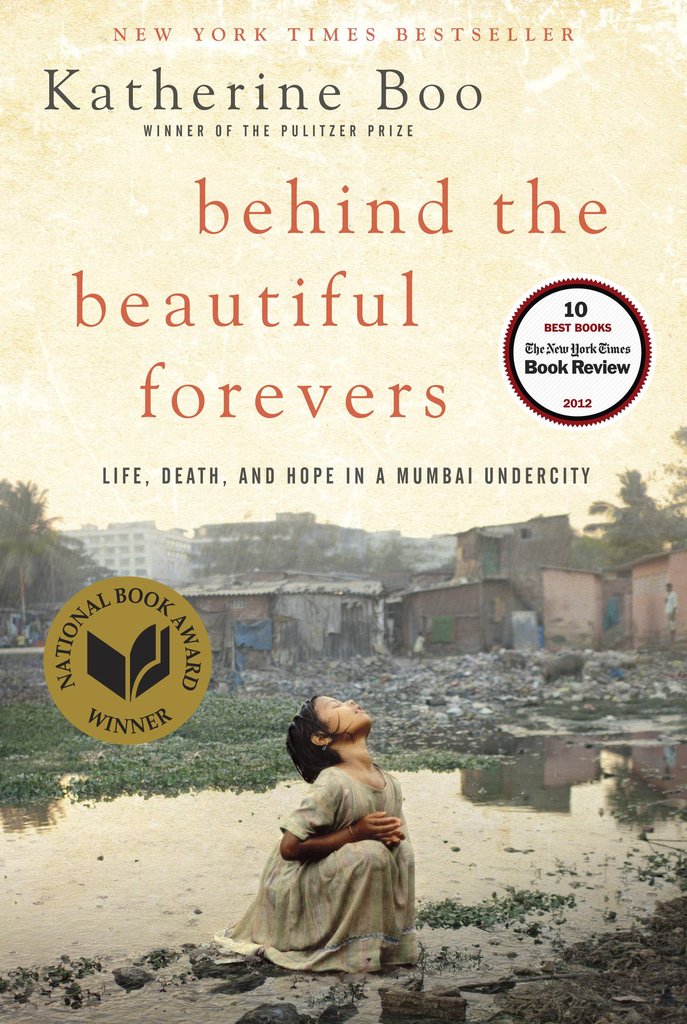

The fiction finalists are:

The fiction finalists are:

“Every year PEN’s literary awards recognize the brightest lights in literary fiction and nonfiction and honor the sustained careers of writers who are distinguished in their fields, raising awareness for a diverse array of outstanding books,” said PEN President Peter Godwin. “These awards represent the best of PEN’s work in defense of free expression throughout the world—fighting censorship, promoting translations into English, and honoring both the new and well-known authors who make up the core of PEN as an organization. Their voices amplify our advocacy work.”

“Every year PEN’s literary awards recognize the brightest lights in literary fiction and nonfiction and honor the sustained careers of writers who are distinguished in their fields, raising awareness for a diverse array of outstanding books,” said PEN President Peter Godwin. “These awards represent the best of PEN’s work in defense of free expression throughout the world—fighting censorship, promoting translations into English, and honoring both the new and well-known authors who make up the core of PEN as an organization. Their voices amplify our advocacy work.” What opportunities are there for younger writers such as yourself to build a literary life/livelihood?

What opportunities are there for younger writers such as yourself to build a literary life/livelihood?