Jyothi Natarajan is an editor and writer based in New York City who has worked in publishing and journalism for the past ten years. She is now managing editor at the Asian American Writers' Workshop, where she edits the Margins and runs a fellowship for emerging writers. As someone invested in the intersection of writing, social justice, and education, she helps run IndyKids, a social justice-oriented newspaper written by youth ages nine to thirteen.

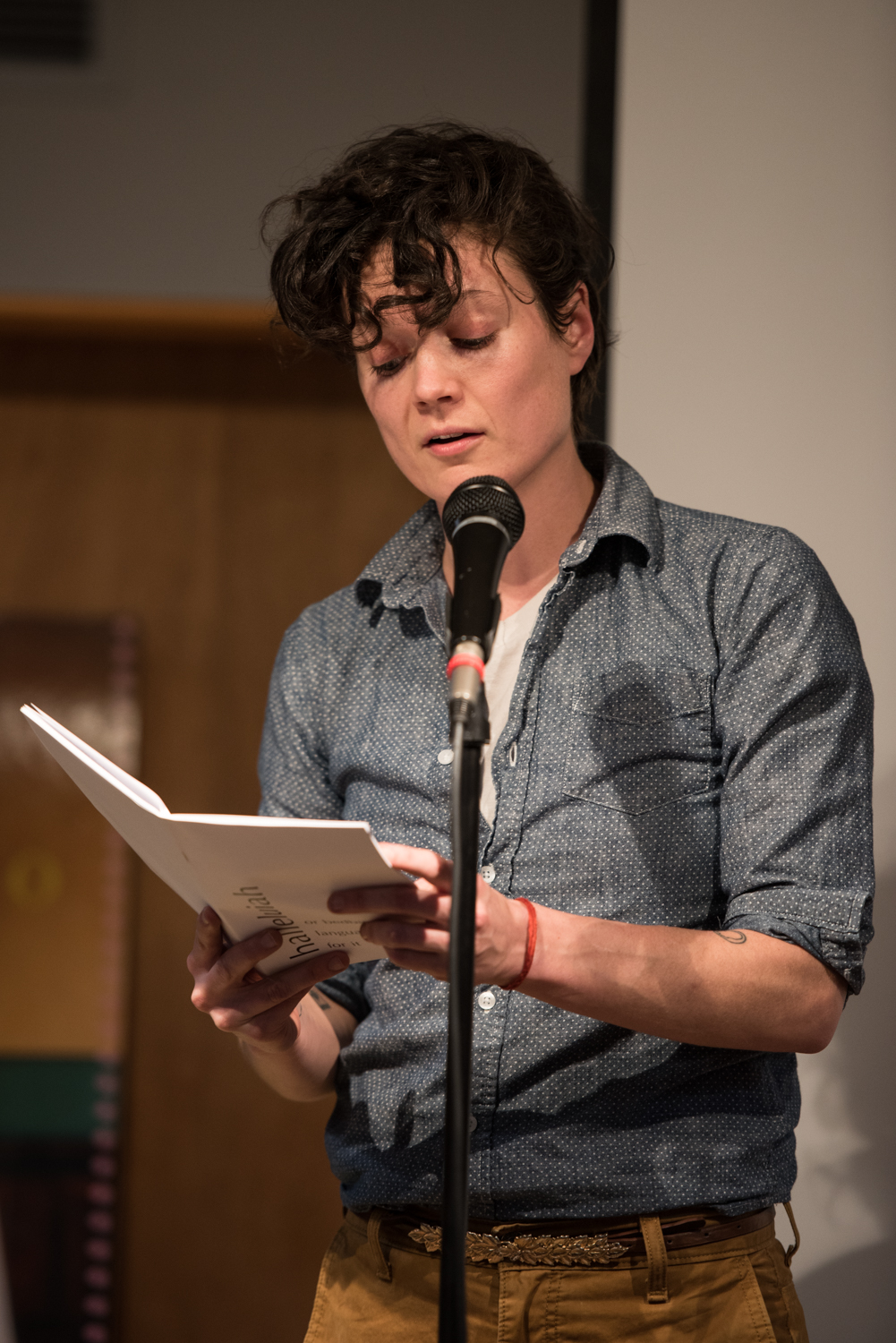

The Poets & Writers' seventh annual Connecting Cultures Reading took place on April 27, 2016, before a generous audience at the Asian American Writers’ Workshop. Ten writers representing P&W–supported organizations Jack Arts, Inc., Kundiman/Adhikaar, National Domestic Workers Alliance, Union Square Slam, and Women Writers in Bloom Poetry Salon gathered to celebrate the diverse literary communities of New York City and Poets & Writers' Readings & Workshops program.

When K Sloan, a singer-songwriter hailing from Detroit, opened the reading with a song, the audience fell into a stunned silence—her voice was just that powerful. "Down, down, down, bring it down," began the lyrics to "Ancestor Song," which Sloan wrote as part of Jack Arts, Inc.’s writing workshop Creating Dangerously. “I wrote these lyrics in response to a prompt asking us, ‘What would it look like to walk with your ancestors? What would you say to her?'” said Sloan.

Joining K Sloan on stage was Sara Abdullah, an indigenous Arab/Iranian/Pin@y mestiza queer Muslima living the diasporic hustle, whose stunning poems were also generated from the Creating Dangerously workshop.

An experimental, performance-based writing workshop for women of color led by a rotating cadre of instructors including Virginia Grise and Kyla Searle, Creating Dangerously received support from Poets & Writers’ Readings and Workshops program, which has provided fees to writers who lead workshops that serve underrepresented audiences since Poets & Writers was founded in 1970. The Connecting Cultures Reading brought together writers who had participated in five such workshops. This year’s reading marked the first time Poets & Writers has featured work from multilingual workshops, bringing writers together with translators to help share immigrants’ stories, like Babita Chhetri.

Chhetri grew up in Darjeeling, India and had been doing childcare and housework for a family in Singapore for nearly a year when she decided she needed to escape from her employer’s exploitation and abuse. Underpaid and overworked, Chhetri did something most workers wouldn't have the strength or courage to do: She ran away from her employer. She had accompanied the family on a summer holiday in New York City and at the crack of dawn, Chhetri crept out of the building they were staying in, forced to leave her flip-flops behind.

"I felt everyone's eyes on me: here was a scared woman in wet pajamas, barefoot, carrying a small bag in her hand. Where could she be going?” Chhetri, who has been in the United States for the past nine years, read on stage from a letter she wrote in Nepali addressed to her daughter and son in Darjeeling. The audience was in tears. Her story was one of ten that were told through letters as part of a workshop called A Letter Home, organized by Kundiman and Adhikaar and led by writers Meera Nair and Muna Gurung.

Through the workshop, Nepali and Tibetan women expressed their experiences as domestic workers, immigrants, mothers, sisters, and daughters. Dolly Sharma joined Chhetri on stage to read her own letter, while the audience followed along with English translation printouts, all the while dabbing their eyes with tissues.

The night shifted from Nepali to Spanish when Adriana Mora, from Aguascalientes, México, and María Guaillazaca, who moved to New York from Ecuador nine years ago, read before the packed audience. Both women participated in a writing program organized by the National Domestic Workers Alliance in which they wrote in Spanish, responding to the idea of home—whether it was where they feel at home, other people’s homes, or the experience of working in someone’s home.

Other highlights from the evening included poet Sam Rush, who began writing poems after developing progressive hearing loss. Rush, who has been a part of Union Square Slam’s writing workshops, read poems that played with their realization of how many words each word could be, leaving the crowd dizzy with the emotional heft of their wordplay. Also a part of Union Square Slam, poet, screenwriter, and essayist Taylor Steele stepped on stage and immediately moved the mic aside. Her slam poems filled the room and left goose bumps in their wake.

Closing the evening were two writers from the Women Writers in Bloom Poetry Salon (WWBPS): Amber Atiya and Jacqueline Johnson. WWBPS, which is now celebrating its fifth anniversary, offers women writers of all levels space to create and share poetic work.

By the end of the evening the room felt much smaller. The stories and words shared so courageously gave even the audience members the strength to say hello to strangers, and share words with the writers who had moved them to tears.

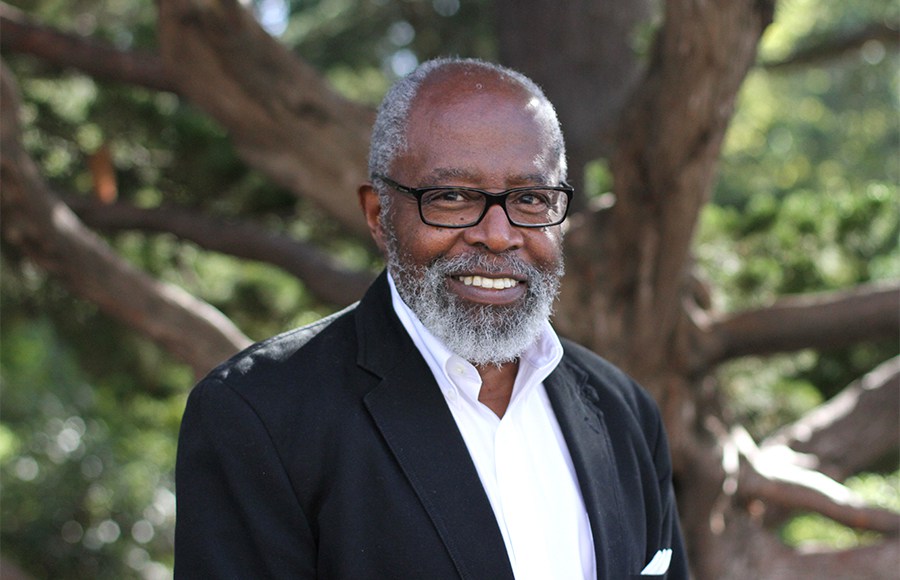

Photo: (top) Readers from the Seventh Annual Poets & Writers' Connecting Cultures Reading. (middle) Dolly Sharma and Babita Chhetri. (bottom) Sam Rush. Photo credit: Alycia Kravitz.

Support for Readings & Workshops in New York City is provided, in part, by public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts, and the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, with additional support from the Louis & Anne Abrons Foundation, the Axe-Houghton Foundation, the A.K. Starr Charitable Fund Trust, and the Friends of Poets & Writers.

A bonus prize of free admission to contest founder Sarah Selecky’s

A bonus prize of free admission to contest founder Sarah Selecky’s