David Mills’ Poetic Arithmetic, Kooky Koans, and Redemptive Communion

David Mills has taught several P&W–supported workshops at the Cook County Juvenile Detention Center in Chicago. He is author of the poetry collection The Dream Detective (Straw Gate Books) and has poems in the anthology Jubilation! (Peepal Tree Press) and magazines, including Ploughshares and jubilat. Mills is also the recipient of a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship. What is your writing critique philosophy?

What is your writing critique philosophy?

Most of the workshops I conduct are with kids, so I always write on the board “2+2=57,” which means for the hour that I am with them, I don’t want them to worry about spelling or grammar because obsessing over “crossed Ts” could mean losing a moment of genius.

How do you get shy writers to open up?

I try to present a model poem that will spark both conversation and creativity. I remind the students that poetry is not on Mount Parnassus. It’s right t/here, wherever we happen to be geographically and psychically. I make self-deprecating jokes to put them at ease and let them know everything is poetic fair game.

I sweat, so I’ll say: “I sweat while I swim. Use that. ‘How can this guy sweat while he swims?’”

I have abstract expressionist penmanship, so I’ll say: “I write like a blind man with five broken fingers. How’s that possible for a poet?”

I don’t want them to write about my idiosyncrasies, but I hope that by framing them as kooky koans the kids will access their own creative centers.

What has been your most rewarding experience as a writing teacher?

Workshops like the ones P&W sponsored at the Cook County Juvenile Detention come to mind. In one visit, I used Randall Horton’s poignant and ironic poem “Poetry Reading at Mount McGregor (Saratoga, NY).” During his own incarceration, he could never have imagined voluntarily returning to a prison, yet in the poem that’s exactly where he finds himself.

I discuss redemption.

What happens for Randall in his poem is what I hope will happen for these kids. Writing gave him a raison d’etre. Horton writes: “tonight poetry is a sinner’s prayer,” and reflects on how when he was incarcerated he “searched for the… alphabets to help me escape.” He concludes the poem: “How do I say welcome me, I am your brother?”

I got misty-eyed as I read those lines. I think the boys felt what the poem was meant to evoke: union, communion.

There were gangbangers in the class from opposing gangs—African-American and Chicano-American. The teachers had warned that certain guys had to sit on opposite sides of the room. As we discussed the poem, guys started talking across “colors,” opening up. Teachers who weren’t part of the workshop stepped in and stayed.

I asked the guys to write about returning to a place—physically or psychically--that might be filled with pain, fear, anger, or an unresolved question. I asked them to describe it physically, but to then address the wound or fear to a person who had something to do with whatever unresolved feeling was back there.

One Chicano student described a town center in Mexico where an incident had occurred that caused his family to flee to the U.S. What happened to his family is less important than what happened to his peers as a result of his avowal. His poem gave his classmates both insight into and greater empathy for him.

What do you consider to be the benefits of writing workshops for special groups (i.e. teens, elders, the disabled, veterans, prisoners)?

I have only worked with male populations where posturing and bravura run deep. But given an opportunity to see that their vulnerability will not be used against them, these boys will open up. I think some of these young men feel—and sometimes rightfully so—like the words in Patricia Smith’s poem, “CRIPtic Comment”:

If we are not shooting

at someone

then no one

can see us.

There is the sense that these boys feel both seen and heard during our time together. In one of the P&W–supported Cook County Juvenile Detention workshops, I used Langston Hughes’s “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”:

I've known rivers:

I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

Hughes’s piece has an epic reach—bodies of water of mythic, cultural, and historic proportion. I talked about Hughes’s “knowing.” I got the boys to write about things they knew intimately, using Hughes’ structure to organize their “knowing.” One participant wrote about the various sneakers he has “rocked”:

I’ve known Nikes, shell-top Adidas...

You get the idea.

Another student had lived in Illinois and Indiana, so he wrote about “knowing” distinct parts of these two states, both in terms of geography but also the “temperature” of different communities.

What's the strangest question you’ve received from a student?

I am pretty zany so no question strikes me as strange. I do get a lot of “Why do you sweat so much?”

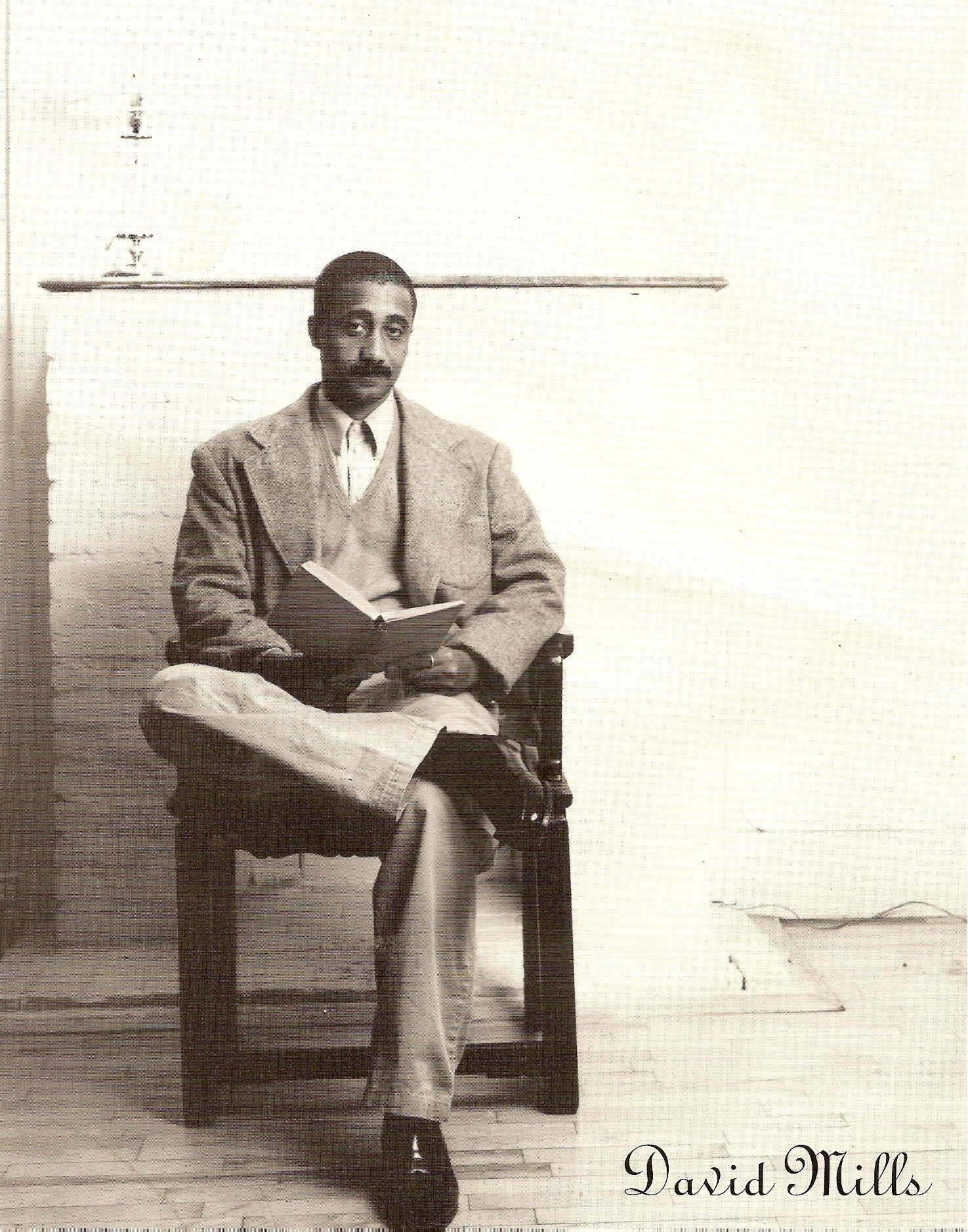

Photo: David Mills. Credit: Luig Cazzaniga.

Support for Readings/Workshops events in Chicago is provided by an endowment established with generous contributions from the Poets & Writers Board of Directors and others. Additional support comes from the Friends of Poets & Writers.

How do you do? Brendan Constantine here with the third “blog” of my residency with Poets & Writers. Thanks for joining me.

How do you do? Brendan Constantine here with the third “blog” of my residency with Poets & Writers. Thanks for joining me.

If only I could embrace the maxim I use in the classroom: Writer’s Block is almost never a deficit of magic but a surplus of judgment. I believe this, I do, but I'm still stuck. This is particularly ironic because what I want to talk about is Speechlessness; a speechless woman and a speechless universe. Maybe I can get this rolling if I work backwards and start with the universe.

If only I could embrace the maxim I use in the classroom: Writer’s Block is almost never a deficit of magic but a surplus of judgment. I believe this, I do, but I'm still stuck. This is particularly ironic because what I want to talk about is Speechlessness; a speechless woman and a speechless universe. Maybe I can get this rolling if I work backwards and start with the universe.

Dances With Wordz: Orisha Poetry, curated by Latinos NYC founder and CEO Raul K. Rios, featured performances celebrating the Yuroba faith of West Africa. The poets, garbed in white from head to toe, were an immaculate presence inside the

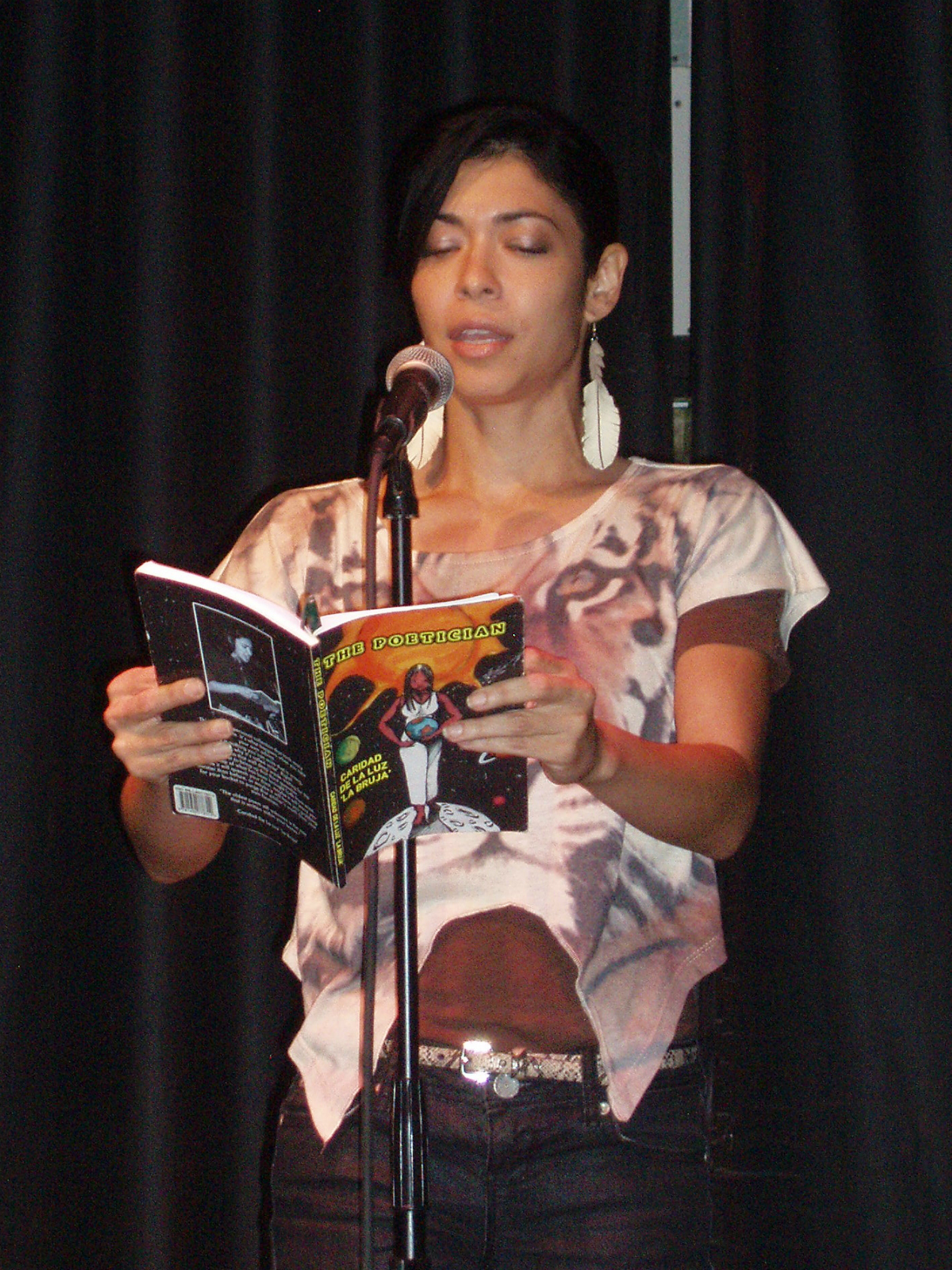

Dances With Wordz: Orisha Poetry, curated by Latinos NYC founder and CEO Raul K. Rios, featured performances celebrating the Yuroba faith of West Africa. The poets, garbed in white from head to toe, were an immaculate presence inside the  Nuyorican darling Caridad “La Bruja” De La Luz read from her first collection, The Poetician, then proceeded to rap and sing after reciting what she fondly called “straight up poetry.” Writer, actor, and painter Iya Ibo Mandingo performed last, conjuring images of home: luscious mangoes and coconuts. He ended his performance with a declarative poem, inciting reactions from the audience, which ranged from the gleeful to the guttural.

Nuyorican darling Caridad “La Bruja” De La Luz read from her first collection, The Poetician, then proceeded to rap and sing after reciting what she fondly called “straight up poetry.” Writer, actor, and painter Iya Ibo Mandingo performed last, conjuring images of home: luscious mangoes and coconuts. He ended his performance with a declarative poem, inciting reactions from the audience, which ranged from the gleeful to the guttural.