With The Emperor of Gladness, published by Penguin Press in May, Ocean Vuong crafts a story of intergenerational connection—of labor, love, memory, and care—while bridging the intimate and the epic, the lyric and the narrative. Since his debut poetry collection, Night Sky With Exit Wounds (Copper Canyon Press, 2016), a New York Times Top 10 Book and winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize and the Thom Gunn Award for Gay Poetry, Vuong has built a body of work that is as linguistically inventive as it is emotionally devastating—a poetics of survival that emerges from the interstices of loss, remembrance, and transformation.

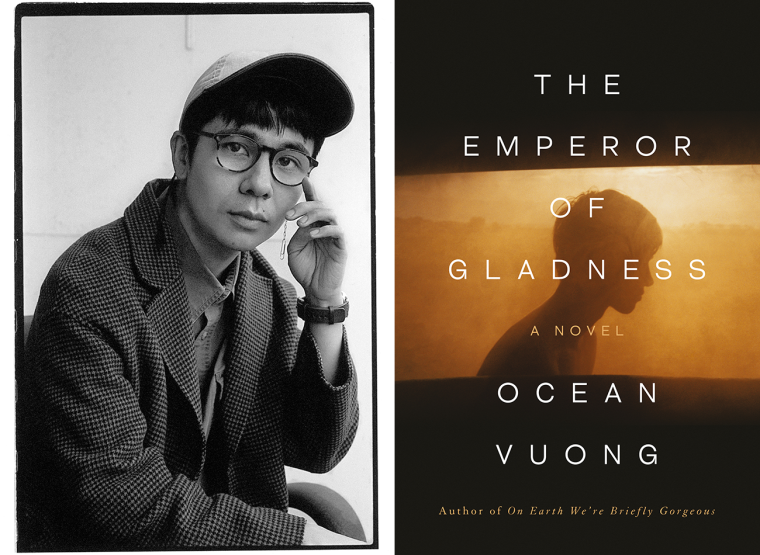

Ocean Vuong, author of the novel The Emperor of Gladness. (Credit: Gioncarlo Valentine)

I first came across Ocean Vuong’s work, more specifically Night Sky With Exit Wounds, in the summer of 2018, while studying at the Sewanee Young Writers’ Conference under Tiana Clark. Clark introduced our cohort to Vuong’s poem “Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong” before asking us to write a poem directed at ourselves. I was stunned by the urgency and vulnerability of Vuong’s poetic voice, and by the way this poem, with its intricate sonic and visual landscapes, presented itself as an intimate offering, a sacred kind of calling. Four years later, I had the opportunity to speak with Vuong directly about his second poetry collection, Time Is a Mother (Penguin Press, 2022), a finalist for the 2023 Griffin Poetry Prize. A daring experiment with both language and form, Time Is a Mother embodies the diachronic weight of grief as Vuong searches for the ability to heal and make sense of life after his mother’s passing in 2019.

Born in Saigon, Vietnam, and raised in Hartford, Vuong is the author of two poetry collections and two novels. His first novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous (Penguin Press, 2019), is a masterful marriage of poetry and the bildungsroman, taking the form of a letter written by a queer young man with Vietnamese heritage to his mother. On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous won an American Book Award, the Mark Twain American Voice in Literature Award, and a New England Book Award. In 2019, Vuong was also awarded a MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship. His work resists the constraints of genre and operates in the liminal space between memory and the present, asking how language can serve as both an archive of inherited pain and suffering as well as a vehicle for renewal. His honors include a Whiting Award and fellowships from the Poetry Foundation, the Academy of American Poets, the Lannan Foundation, the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, and the Elizabeth George Foundation. He currently serves as a professor in Modern Poetry and Poetics in the MFA program at New York University, where he received his own graduate degree in poetry.

In his fourth book, The Emperor of Gladness, Vuong attends to the rhythms of labor, community, and survival in contemporary America. Forming the nucleus of the story are Hai, a queer young man struggling with addiction, and Grazina, an elderly widow with dementia whom Hai begins to care for. In their unlikely companionship, Hai and Grazina redefine what family means and how it can be constructed. In his second novel, Vuong gestures toward autobiography once more; as just one example, the name of his protagonist, Hai, means “ocean or sea” in Vietnamese (when spelled “hải”). Vuong, however, intentionally keeps elements of his lived experiences distinct from this narrative. Set in the fictional, post-industrial landscape of East Gladness, Connecticut, the novel opens with Hai standing on the edge of a bridge, only to be rescued by Grazina. This novel extends Vuong’s explorations of existing on the margins, grappling with the emotional and psychological peripheries where isolation, thoughtfulness, and resilience coexist. The Emperor of Gladness is a testament to the ways we find—and carve out—a sense of home in one another. As he has continually done in his work for the last decade, Vuong insists on the radical possibilities of tenderness and communion, and on our ability to remain in awe of this world even as our lives and the structures we rely on may be fracturing. The Emperor of Gladness offers readers a special gift: the practice of looking carefully at the world around us, and at the people who surround us, with more meaning and care.

In the opening pages you lean into the plural first-person and second-person points of view, among others, creating an urgent invitation for the reader that quickly implicates us in a sense of guilt. (“He had not been forgiven and neither are you.”) Why did you choose to begin the novel this way?

I wanted to settle into the narrative voice rather than having the voice come preformed and predecided. The first chapter is like an accumulation of debris, like ash in a glass of water that has started to settle. As a poet, I am skeptical of the question of authority in a literary work. I wanted to be nebulous with the center: to present an indictment without a center, without a subject. Where is the novel coming from? There are no names in the novel until the characters learn the names—the protagonist is, until then, referred to as “the boy” or “he.” I wanted to pull the heat of the work out of the center. I was not interested in a centralized voice of omniscience.

In the summer of 2015 you published an autobiographical piece entitled “Beginnings: New York,” which includes strikingly similar details to The Emperor of Gladness. Yet there are also deliberate differences between the essay and your novel. Can you speak about how and why you chose to transform certain features of your personal history for this book? What role does this kind of narrative distancing play in the process of fictionalizing your lived experiences?

I am disinterested in replication; for me, it is more about transformation. The context of my life is what is “true,” and the imagination animates it, creating a parallel universe. Similar to On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, the pieces of my life are here, but the novel is a parallel, different trajectory. To me, that is what is most exciting about fiction. It turns what is known into the unknown. It feels boring to make the known into [that which is] more known. In the West we love this idea of the distanced genius writer who somehow is not part of the world or inspired by the world, but cloistered away from it, sanitized from community to catch a pure creative spark. I am not interested in that. My novel is a fictionalized rendition of something I have lived through. There is also an ethical component to the process: I don’t speak about anything, but beside things, an idea I borrow from [filmmaker, composer, and theorist] Trinh T. Minh-ha. I take this a step further: I don’t speak for anyone. I did live with a woman named Grazina; I named her Lina when the essay was published in 2015 since she was alive then. The stories that she told me, the things we shared together, I’ll never tell anyone else. I’ve also never interviewed my family members for my work. I just couldn’t sit there and say, “Tell me your trauma so I can turn it into art.” I observed, and the rest I had to research and make up. It’s important for me not to tell another person’s story, but to be inspired by their life.

In several passages you render the body into a vessel for stories and histories—a theater of memories. Do you see bodies, especially those shaped by labor and trauma, functioning as living archives in this novel?

The somatic experience is one of inspiration and livelihood. Labor coincides with storytelling, going back to the beginning of our species. The narrative art of cave painting gestures toward the fictive and mythological. There is a hybridity between lived life and the fantastical. To me, the fracturing between these only happened in the twentieth century, when we cloistered storytelling into the upper and middle classes. But that doesn’t mean that the working class does not have stories; they are just [told] through different mediums: oral traditions, jokes, folklore. I wanted to disturb those fixed borders and return to the primordial renditions of storytelling. The body becomes the record of memory. Ultimately, the book is interested in the moral potentials of the fictive. What is fiction? What is deception? Deception, in the West, has often been deemed a corrupting vehicle. Witches, queer people, and people of color are often the ones who deceive, who are obscure and obfuscated, who have spells. My characters don’t have much to give each other; they don’t have money, much time, or generational wealth. All they have is their bodies. And so, they create fabrications, often in order to help each other. This is a kind of benevolent deception.

Not only does the novel open on a bridge but, over the course of the novel, Hai and Grazina also build “bridges” for each other through language, music, recollection, and care. Can you talk about the motif of bridges—both literal and spiritual—as it resonates so powerfully in your work?

That’s beautiful. I think the bridge is often seen as a utilitarian tool to go from one place to another. But there is an obvious liminality to it, of not being on technical land. It gestures toward this wonderful allegory of refusing. What happens if we live on the bridge metaphorically? What happens if the bridge becomes a medium to another world, which is what death is in the Buddhist ethos, continuing into another realm. And so, the book begins on the bridge, in a negotiation with death. When the world rejects you, when you’re out of options, the bridge can be recast as a jumping off point, literally, a start to the novel. Death and destruction are often plot points to resolve and finish a novel. I was so curious about what would happen to someone who is so hopeless but then decides to live. I had to write a novel out of that. Here, hopelessness leads to a denial of death. Being forced to live after deciding you have nothing to live for is a really exciting and interesting fictive place for me.

I was inspired by Chen Si, a Chinese man who has rescued over four hundred people from suicide on a bridge in China, and he’s dedicated his entire life to going [ten times a day] and waiting on the bridge. What if we follow one of those people home? What is the afterlife of the decision to live when you don’t want to? What is the afterlife of the end of the line? I’m so interested in that because suicide has been so close to me, my family, and my community. For Asian American youth, it’s one of the biggest killers. It’s often misunderstood because the model minority myth has people assuming that Asian Americans are just thriving. The bridge is a charged metaphor of the what if—what if we decided to live on the bridge, to stay on the bridge? In the book, there is no improvement arc. Nobody gets a better job, nobody goes to school, nobody leaves the town. The commercially informed arc of improvement is the fetish of our Western culture. Your characters must change: a reversal of fortunes, rags to riches. He gets the girl; she gets the guy. You find the body; you find the killer. There’s a cathartic resolution that becomes mimetic of buying products that promise something. Fiction starts to follow the production values of this culture. I denied that project for myself and decided there was going to be no change for my characters, but there would be transformation: transformation without change.

When we last spoke, you mentioned that the question you were preoccupied with was: “How do people care for one another when they don’t know how to express care to those closest to them?” You have so tenderly addressed this subject in The Emperor of Gladness. Your characters provide care that emerges from deep frustration—with the past, intergenerational trauma, deeply-rooted systemic injustices, and societal neglect.

Even though we were speaking about Time Is a Mother, I was writing this book by hand at that point, and it was on my mind. The central question I had was: Where does care go when there is no change that can happen? I am so interested in this question at this time in our culture. What is the cost of kindness when you don’t have anything, when there is nothing to benefit you? What happens when people decide to give anyway? I was inspired by Mark Fisher, one of my favorite cultural theorists, who took his life in 2017. He wrote that our youth are diagnosed with apathy, with learned helplessness. But Fisher pointed to reflexive impotence, stating that the youth are not apathetic, but that they acknowledge there is no hope, there is no dream. Prosperity is an illusion. So much of my community and my family live that way. Their lives are so stagnant, and it’s not because they don’t want to improve. There are glass ceilings at every level. It doesn’t mean that their lives are worthless or meaningless. Through fiction I want to animate life as it is, the fact that even when some know nothing will make a difference, they still help each other.

In the novel Grazina asks Hai, “You wanna be a writer and you want to jump off a bridge? That’s pretty much the same thing, no? A writer just takes longer to hit the water.” Her understanding of a writer is darkly humorous, but also points to the vulnerability inherent in creating art. Do you see writing as an act of risk?

As a writer you’re asking to use the bridge differently, to test the meanings of words, of metaphor, of the sentence, of story, of realism. It’s also an act of daring. When jumping, you risk losing your life, but you also risk surviving. To me, the cost of writing is felt in all of my work. I know that because I’m lucky enough to have people interested in my work, I get to have a life, I get to be a professor, I get to move out of the poverty I grew up in. But it’s also very fraught. I take care of seven Vietnamese refugees, for example. And I’m only able to do that because my work has been deemed “valuable” to the center. I have entered a reified position in order to sustain my family. I’m here through a kind of fantasy. I’m not really supposed to be here, right? I didn’t even know you could be a novelist or a poet until I had almost graduated college. My mom told me to go work at McDonald’s, and she was serious. We lived in Section 8 housing, and if your family made too much money, you would be kicked out. Working at McDonald’s was sort of a strategic poverty so that our rent could stay the same, because we could not afford a house on the open market. It was a strange experience as an immigrant, because often there’s a myth of upward mobility. But for us, it was too dangerous to have those dreams.

You’ve said before that writing is like “a prayer in the dark.” What does the prayer of this book illuminate?

For me now, the prayer is less aspirational and more about completion. I want to use the technology of the novel to give space for these ideas to be shared. By prayer I mean always keeping the North Star of your deep ambition visible and clear, to keep that integrity of what you want to achieve close to you. I tell my students to never assume an audience, because then you’re just putting scarecrows in your room when you’re writing. What you’ll do then is reduce your work to satisfy these fantastical projections, and you’ll lose your idiosyncrasy and your curiosity. In this book I’m interested in strangeness: stomping on bread, climbing into garbage dumpsters, making origami swans but then calling them penguins when you cut off their wings. In Western fiction there’s a kind of tyrannical, brutal linearity. I’m interested in something antithetical to that. Consider Miyazaki’s work, and specifically the scene in Spirited Away on the train when the characters are just sitting there. A Western editor might cut that out because there’s “no point.” But in Japanese storytelling there’s a term for this moment of absolute rest, Ma. It builds resonance within the story so that you can perceive how the characters are embodying the weight of the plot. I’m interested in that as [being] counter to this idea that everything must serve the plot in a tyrannical way. And if it doesn’t, it’s somehow erroneous, disobedient, decorous. Culture at large punishes us for ruminating and daydreaming. But these are just parts of being alive.

You gesture to Noah’s Ark in many of your works. Do you view Grazina’s memory itself as a kind of Noah’s Ark, retaining the most important elements of her personal history?

That is what I wanted to showcase with Grazina. Even with her memory loss, she is continually adding to her Noah’s Ark. She is even more of a novelist than Hai. Through role-play she drags him into this fantastical world-building, a kind of novel within the novel. Even though she is deemed pathologically ill, she has more of an inventive capacity than Hai does. He is following her; he is the coauthor of the story she is writing. I believe a novel is much more interesting when other characters decenter and dissolve the agency of the protagonist. Grazina keeps testing Hai, challenging his assumptions, even changing the year they are in through role-play, turning pathology into possibility. Only fiction can assemble these moments.

You have called On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous your artist’s statement. Previously we discussed how Time Is a Mother challenged or honored it. Can you describe how The Emperor of Gladness exists in relation to your artist’s statement?

You can’t write more than one On Earth. At least I can’t. On Earth is very deliberately an artist’s statement, a treatise. It’s seen as a faux pas for a novelist to pontificate and to offer philosophical readings of the world in a novel. But I needed to do that before I could write a “traditional” novel and bildungsroman, which I would say Emperor is. I wanted to start my career by explaining why it was important and fraught for me to write a novel. There was a before. There was a historic pressure at work, and I had to bring that pressure forward first before I could write a more plot-driven novel. On Earth was my blueprint, and Emperor is my attempt to build on that and to enact the thesis of On Earth. They are really tied together, but they have no sequel/prequel relationship. Perhaps Emperor would be the debut novel of Little Dog [the narrator] in On Earth, if he were to write a novel. That was my North Star. He would not write about his mother, as that’s too close to him. If he is going to face the world, he must turn the project into a public-facing novel; he must choose what parts of his life to tell and what parts to keep close. I wanted this novel to move like a river, like the Connecticut River I grew up beside. I wanted to capture this one-way force that just drags you—time and the seasons gathering and gathering—and then spits you out at the end. The rhythm of that river haunts this book; it is the engine of the book.

You described your debut novel as a flower sprouting from your personal soil, suggesting that it was a blossoming of your ethos and worldview. With The Emperor of Gladness, what new roots are taking shape beneath the surface? Where do you see your writing, teaching, and life branching out to next?

I often tell my students, what is most visible in the garden is the flower, but the detachment during harvesting is the beginning of the flower’s death. The hardest work is tending to the soil, enriching it. The soil sustains, it asks you to think about the past and the future, while the flower is just an ecstatic, ephemeral act of harvesting. I have dreams of other books, but I never plan or work on others until I am done [with the project at hand]. I should write books faster so we can talk more often! Last time we spoke, Time Is a Mother was at the printer, and I was beginning this one. But I don’t assume writing is a career for me. I have written four books; that’s four more than I thought I would ever write. If that’s it, that’s a great life. For me, teaching is a career, it’s a vocation. The books feel more like discrete events. I hope I can build toward others, but even if I don’t, I nourish my soil: I read, think, consume art, consume the world, build relationships. If you keep enriching a plot of soil, even when you move away, something will grow.

Divya Mehrish is the associate director of content at the Adroit Journal and a graduating senior at Stanford University, where she was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. A writer from New York City, she has received nominations for the Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, and Best Small Fictions, and has been recognized by the UK Poetry Society. Her work appears or is forthcoming in Prairie Schooner, PANK, Arc Poetry Magazine, the Adroit Journal, Cimarron Review, Gigantic Sequins, and Amtrak’s magazine, the National, among others.

EXCERPT

“Come in. But take off your shoes. My husband put down these floors.” The woman disappeared into the house. The boy hesitated, looking down the empty street. The rain was picking up again. He stepped onto the porch, water running off him in rivulets, took off his boots, and followed her inside.

A creaky rail house built by freight workers over a century ago, the home was one large hallway divided into three rooms: a parlor, a dining room, and a kitchen, whose dim light now glowed at the far end like the hearth of an ancient cave. Furnished in a style the boy had seen only in the black-and-white TV series Lassie, whose reruns he watched on a three-channel Panasonic as a kid, the house had the stuffy odor of rooms whose windows rarely opened undercut with the mildewy rank of crawl spaces. As his eyes adjusted, amorphous furniture upholstered in sprawling pale florals came to view. The walls were wood-paneled and adorned with cheap landscape paintings in gilded frames. As he passed the transom that divided the parlor from the dining room, he looked up and saw what was once a white cross, now phantom-grey from decades of dust. On one wall, lit by streetlights, a cluster of grim-faced portraits stared out from an era he couldn’t locate. He paused at the kitchen’s threshold, water falling from his chin and hair on the laminate floor.

The woman sat down at a small table and nodded toward an empty chair. “Go on, sit. You look like a dunked cookie.”

He sat carefully, his eyes taking in the room. Not knowing what to do with his hands, the boy placed them, palms up, on the table but withdrew them to his lap when he realized this looked psychotic.

“Here, dry yourself.” She handed him a dish towel. It smelled of raw onions but he wiped his face anyway, his eyes quickly stinging.

“Poor kid,” she mumbled to herself. “Hey, it’s all over now, okay? Whatever happened is over. But don’t you cry, boy. Tears deplete your iron, you know.” She grabbed the rag, leaned over and dabbed his eyes some more, deepening the burn. He winced and turned away. “Okay, you’re not a boy. You’re a man and don’t need nobody to wipe your tears.”

The kitchen was the size of a large shed and contained a stovetop browned with grime-stuck grease, a sink, and a portion of countertop the size of a cutting board. They sat at a round table covered in plaid plastic meant to look like picnic cloth. From its center, a fabric-shaded lamp trimmed with tulle emitted a sickly amber glow.

She grabbed a nearby pack of cigarettes, a brand he didn’t recognize, slipped one between her lips, and put a lighter to it. “I normally don’t smoke.” She took a drag and stared at him, not unkindly, then leaned over and pushed aside a large stack of magazines. They were decades old and printed in a language he couldn’t make out.

“Lithuanian,” she said, clocking his curiosity. “Know what that is?”

He shook his head, wiping the onion tears from his cheeks.

“An old country, far away, where I was born.” She waved the cigarette about and took a drag. “But all countries are old, if you think about it.”

But he had never thought about it. He had rarely thought about any country, least of all the one he was born in—only that it, too, was far away.

“Want one?” She handed him a cigarette.

Before he could answer she placed it in his mouth and lit it.

“You like my owls?” She pointed over her shoulder where an armoire loomed behind her. Behind its glass doors was a fleet of owl figurines of many shapes and sizes, some porcelain and shining, others the matte of wood or clay. “Every owl was made in a free country. None of my owls,” she leaned back, “came from Communists. Understand?”

He lied by nodding.

Above the armoire were three paintings of owl portraits, their faces bloated as old mobsters, each one depicting, like a Rembrandt study, a new angle to the bird’s face. In fact, owl knickknacks, tchotchkes, and icons stared at him from nearly every surface. “I collect them. Don’t know why really,” she shrugged. “People started giving them to me long ago. Now it’s my calling card.” She smiled weakly through the smoke. “What’s your name anyway?”

“Thanks for this.” The boy took a long drag from the bogie. “But I should go.”

“Easy, little lamb. I invite you in my home, give you cigarette. And look,” she tilted the pack to show him, “I only have two left. I even let you cry in my kitchen. You know it’s bad luck to cry in the kitchen, right? You can at least tell me your name.”

He stared at the plastic coverlet on the table pocked with holes and considered the name his mother gave him, the thought of it sinking him. It wasn’t that he didn’t like his name—only that he had been willing to toss it in the river. He had never wanted to throw his name out, just the breath attached to it. The name, after all, was the only thing his mother gave him that he was able to keep without destroying.

“Hai,” he mumbled.

“And hello to you too. But—”

“No, Hai. It’s—”

“Okay,” she breathed, “but who am I saying hello to?”

“My name is Hai.”

“Your name is Hello?”

He decided to nod. “Sure.”

“Ah.” She brightened and pointed a crooked finger at him. “So your name is Labas!”

“What?”

“Labas means ‘hello’ in my country.” She extended her hand across the table for him to shake. “Hello, Labas. I’m Grazina. Means ‘beautiful.’” She grinned, the cigarette smoldering through her yellow teeth.

He shook her hand, cracked dry and warm. “Hello.”

From The Emperor of Gladness by Ocean Vuong, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Ocean Vuong.