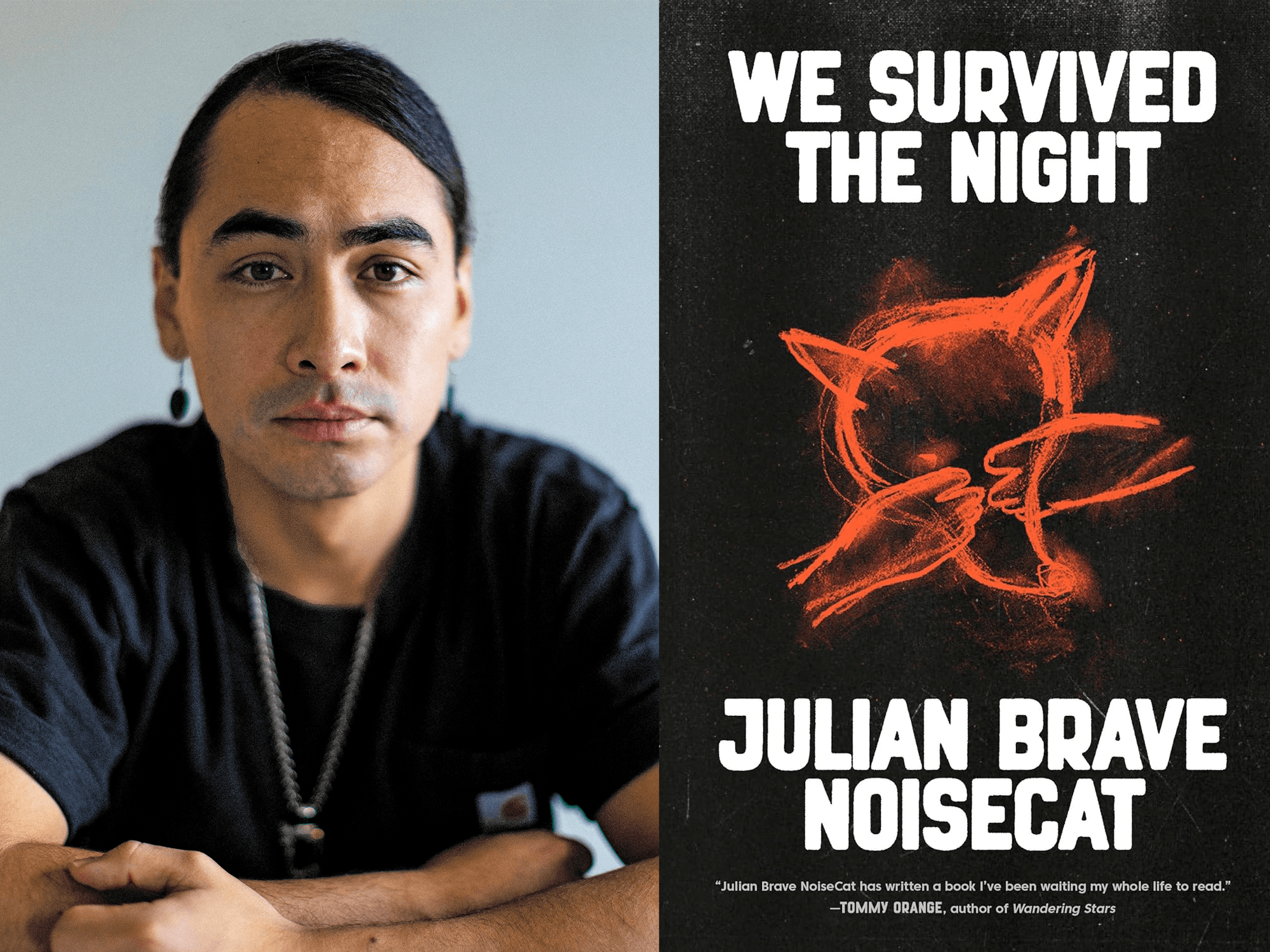

We Survived the Night (Knopf, October) by Julian Brave NoiseCat, an intricately woven story that brings together reportage, oral history, memoir, and mythology to conjure a startlingly clear account of the past and reaffirm an Indigenous present and future. Agent: Alice Whitwham of the Cheney Agency. Editors: John Ingold and Jordan Pavlin. First Lines: “A golden feast ladle earring dangled from my father’s left lobe, its glint partially obscured by his thick mane of shoulder-length jet-black hair. Dad had gotten all dressed up for his first night out at the disco.” (Author photo: Emily Kassie)

![]()

A few days before the summer solstice, I sat against a tree turning the pages of an advance reader’s copy of my first book, We Survived the Night. Parched and hungry as hell, I was at the edge of the woods in Esk’et, a remote Indian reserve in British Columbia, Canada, that’s not too far from Canim Lake, the slightly less remote Secwépemc rez where my father grew up. It was the third day of my four-day, four-night commitment to abstain from food and water. A sacrament I’ve maintained for four years. As I prayed and reread the book, I arrived at the final chapter, “Esk’etology,” about the spiritual colonization of my people, our beliefs regarding death, and my personal journey to reclaim what was taken from us by participating in ceremonies like this one. Then it started to thunder.

Four years ago I set out to write what I hoped would become a definitive account of contemporary Indigenous life in the United States and Canada. The book I originally envisioned was a chronicle of a people who remain foreign to most of the world. Then two things happened.

First, I got a call from my friend Emily Kassie. More than two hundred potential unmarked graves of children had just been discovered on the grounds of a former Indian residential school not far from Canim Lake. Emily and I worked our first reporting jobs together. She wanted to collaborate on a documentary film following an investigation at one of these segregated boarding schools designed to assimilate Indigenous kids. When I accepted her offer, I didn’t know Emily had already chosen to focus that documentary on St. Joseph’s Mission, the school my family was sent to and where my father was born.

A few months into filming I made another consequential decision: to move in with my dad, an artist with whom I’ve had a complicated relationship after he abandoned me when I was a little boy. I was raised by my white mom in Oakland, a city a long way from my people but with a large Native community. I’ve spent much of my life as a journalist and human being trying to understand the identity and culture of my new roommate, the guy who left. As society reckoned with the cultural genocide perpetrated against Indigenous peoples and with my formerly distant father now sleeping across the hall, my book took a more personal shape.

Between reporting trips I spent nights hanging out with Dad to learn about his life and repair our relationship. I spent days reading centuries-old oral histories gathered in the dusty volumes of seldom-read ethnographic studies. I found myself drawn to the ones about Coyote, the trickster forefather of our people. In these tales of the epic misadventures of a great rabble-rousing creator and destroyer, I started to see much of my dad and, eventually, a great deal of myself and the Indigenous world I move through and report on. Before colonization, our people understood ourselves to be Coyote’s descendants, and the ideas running through the stories about him animated our world. Who’s to say we aren’t Coyote People living in Coyote’s world still?

This flash of insight fundamentally reshaped the book I was writing, which became not just a report on a resurgent people, but also an act of recovery of self, family, and tradition. Through countless drafts and the deft guidance of my Knopf editor Jordan Pavlin, consulting editor Carrie Frye, my agent, Alice Whitwham, and my longest-standing reader—my mom—I rewove Dad’s and my story with that of a trickster ancestor, bringing a nonfiction art form nearly annihilated by colonization back to life on the page.

It is my hope that We Survived the Night contributes to the global renaissance of Indigenous arts and storytelling and the ongoing effort to reclaim what was taken: identity, culture, narrative, and much else. Because this land and era deserve new stories, myths, and perspectives. And ours, though nearly wiped out, still get at beauty unseen and truth overlooked.

An excerpt from We Survived the Night

At some point, after he stocked the rivers with salmon and peopled the villages with descendants and in-laws, Coyote disappeared. Of course, he did not die—at least not permanently. Coyote, like the Coyote People, could not be put down forever. He would come back. Someday . . . probably? And we would too. At least that’s what the Coyote People believed back when we still called ourselves Coyote People.

The most common account held that Coyote would reappear in the End Times. When things came full circle, the trickster who molded the world into its Indigenous state would be there. Just to do whatever trickster shit needed to be done—make something, like a son; or break something, like the witches’ fishing weir; or steal something, like goose eggs or a wife; or invent essential ergonomic functions, like the elbow; or live a life full of damn good stories. Because how the world ends is just as important as how it begins.

Some said Coyote would reappear as a cooler version of Jesus. Cooler because if you listen to stories of his feats, Coyote resurrected way more than just once and did more to create our world than Jesus. Jesus died for our sins, and yet thereafter we were still sinners who could be damned to Hell. In the single act of liberating salmon—just one of many feats—Coyote provided over half of the Coyote People’s calories most years. While Christianity hands down eternal sentences for life mistakes, Coyote fills bellies, lives his own mistakes, and laughs about it all. According to a belief common among the Coyote People in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Coyote’s next coming would mark the renewal of the world and the return of an old and good Indian way of life.

Christians fingered Coyote as the Antichrist. Many believed the Indian way of life was the Devil’s work. That the Coyote People and our beliefs were wrongheaded, and that we would be punished for all time if we did not renounce Coyote and follow Jesus. And to make sure we did, they kidnapped our children and took them to schools where kids and even newborns were physically, psychologically, and sexually abused, assaulted, traumatized, neglected, diseased, starved, raped, and sometimes even killed.

I have come to see Coyote as creator and destroyer, messiah and Antichrist, forefather and deadbeat dad. He is the embodiment of forces greater than ourselves that drive and ride the metamorphoses of the world: of climate, geology, environment, technology, and culture. Coyote was change incarnate. And as his descendants, we carry that same power of transformation. Colonizers tried to remake us in their image or kill us—physically, legally, and culturally—countless times by countless means. But every time we came back, not as whitewashed primordial cultural goo, but as ourselves—as distinct peoples with prior and rightful claims to these lands carrying in our culture, memory, and blood the knowledge of how to live well upon them. To survive, we remade ourselves and the world around us in whatever way we could—often, and especially, by getting into trouble like Coyote, who broke that fishing weir, or my pé7e Zeke, who, amidst a genocidal apocalypse, almost single-handedly repopulated the Coyote People all up and down the Fraser River watershed; or my dad, who narrowly escaped the incinerator and many other brushes with death to bring the NoiseCat name and family back from the Land of the Dead.

From the book We Survived the Night by Julian Brave NoiseCat, Copyright © 2025 Julian Brave NoiseCat. To be published October 14, 2025 by Alfred A. Knopf Books, a division of Penguin Random House.