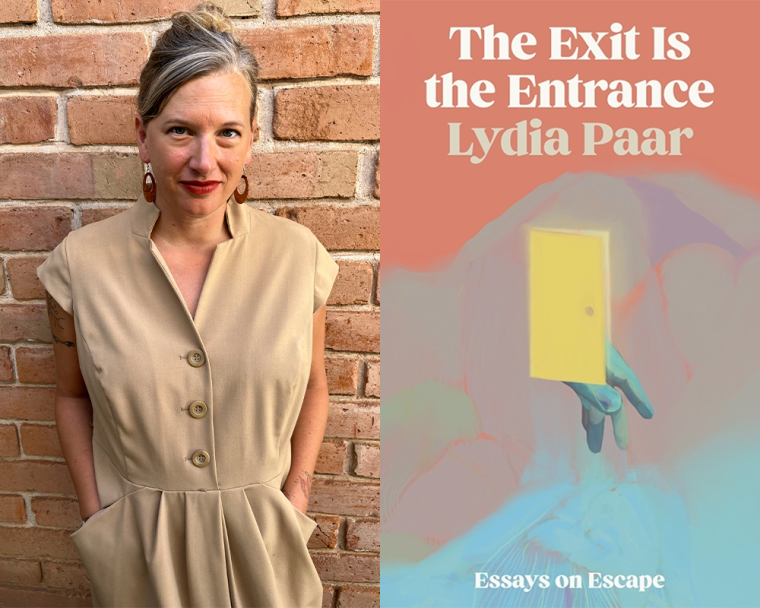

The Exit Is the Entrance: Essays on Escape

Lydia Paar

Lydia Paar, whose essay collection, The Exit Is the Entrance: Essays on Escape, was published by University of Georgia Press in September. (Credit: Rachel Koch)

The Cockroach Prayer

Although Sergeant Driver wasn’t entirely right about the equal-opportunity nature of the army, at least most of the time the chain of command treated all the trainees like equal puddles of pond scum. About a week or two after we arrived, two of the female drill sergeants took the women from my platoon into a large ladies’ latrine and gave us a talking-to about what it means to be a female in the military. They were the buggy-eyed one and the one who wore makeup and never raised her voice. (“If I get to the point of yelling, I’ll just smoke you,” she used to say calmly.)

What they said went like this: Don’t fraternize with the males, for fuck’s sake don’t sit on the toilet seats, always wash your hands, eat extra food during your period, and if your period stops, it’s normal with all the pt we’ve been doing, so don’t worry about it. At the end of this “discussion,” I had to admit, I started to feel like they cared about us especially; here they were, taking their time to forewarn us about the dangers of STDs, the ways our particular bodies would change, and disciplinary trouble with boys. At the end of it, though, the makeup-wearing drill sergeant stood up, put her finger to the corner of her plum-colored lips and said, “Now, get on the ground.” And they had us do push-ups for half an hour, right there in the powder-blue latrine together, our hands pressed at odd, cramped angles on the tiles.

At the same time that our unit began to get used to the grim monotony of basic training, other moments became memorable against the swirl of routine:

The Alpha Pathfinder platoon learned how to belay and rappel. We ran beforehand, a tactical run, scattered across a thicket, one soldier every few paces, through the wood to the field station where our drill would be conducted.

There, in the ground next to a narrow pine tree, hid a gnarled brown root. It hadn’t moved in years, and water had rushed below the center of it, making the root into a kind of trap for the toes of combat boots. I saw it just before it grabbed me and took me chin-to-ground. My glasses had gone flying, and I would be screwed if I didn’t get them before they were crushed. But when I tried to pull myself up to scramble for them, I realized I couldn’t really move. Then I realized I couldn’t really breathe, but there was a drill sergeant coming, so I had to move. I felt myself inhale sharply as I was pulled up from behind by my ammo belt. The pressure on my chest vanished. Someone had got hold of me, and as I was returned to a flat-footed stand I realized it was Private Neil’s giant-sized hand on my left shoulder, righting me.

“You okay?”

“Glasses!” I stuttered, and he leaned over to lift them out of the leaves.

“Thanks, man.”

“Yeah, you okay?”

“I think so.”

“Try and jog, then.”

I tried. I could do it a little. My lungs felt a little like a bellows stuck shut. I wondered if I’d popped a hole.

“The Cockroach Prayer” from The Exit Is the Entrance: Essays on Escape © 2024 by Lydia Paar. Courtesy of the University of Georgia Press.