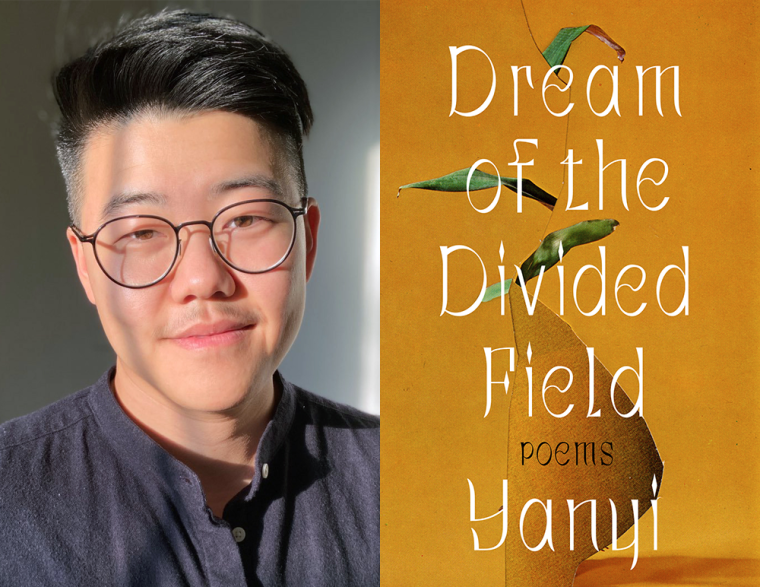

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Yanyi, whose second poetry collection, Dream of the Divided Field, is out today from One World. Many of the poems in Dream of the Divided Field concern a separation of lovers, and the poet’s use of the second-person singular implicates the reader: “We get to the room and I’m dared / to agree: you’re the monster. / I neither lie nor tell the truth / for both of us.” Throughout the collection, Yanyi remains this attuned to relational dynamics, and troubles the reader’s expectations. In a Caesarean section, is it the doctor or the newborn that cuts the mother open? “My mother has a long scar from where I, or they, cut her.” Written with great tenderness and intimacy, Dream of the Divided Field reveals what we do (and do not) owe to others, and what we owe to ourselves. “Here is a book of the body, a book like no other,” writes Ilya Kaminsky. “Yanyi is a terrific poet, one who’s written for us a book to read when we wake in the middle of the night and need a voice that is filled with longing, truth, and delight of being, despite all the painful odds.” Yanyi is a writer and critic. He is the author of The Year of Blue Water, which won the 2018 Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize. His work has also been featured in Tin House, Granta, and A Public Space, and at the New York Public Library. The recipient of fellowships from the Asian American Writers’ Workshop and Poets House, he is the poetry editor of Foundry and gives creative advice at the Reading.

Yanyi, author of Dream of the Divided Field.

1. How long did it take you to write Dream of the Divided Field?

Active work on the book was between 2019 and 2021. The composting scraps, though, came mostly in 2018. For half of 2019 I plowed forward with an idea of a book without the book. Then summer came and there was a lightning moment, a moment when the cup overflowed.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

It being my second. There is a strange tension between fear and hubris. Fear of never publishing again—the Yale Younger Poets curse—and fear of running out of money and therefore running out of time. Hubris because having written one book, I thought I knew the way for another. What I wrote, how it was ordered, how I edited it—this book was completely different. I had to fumble through again. My comfort is in how that is the same.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I have an office and I like to write in the early morning. But reality rarely follows intention. I still write almost anywhere, often on my phone or a notebook, chasing dreams or the dog. But in the office I will write in a word processor. Recently, in Adobe Garamond.

4. What are you reading right now?

The Complete Adventures of the Borrowers by Mary Norton and, intermittently, a translation of the I Ching.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

A few years ago I would have said Linda Gregg, but I feel as though she has been receiving exactly that. Linda Gregg led me to Laura Ulewicz, whose work is not currently in print, a fate that comes to many deserving writers for systemic reasons. Kazim Ali, who innovates hybrid forms from book to prolific book. I also love Agha Shahid Ali, a poet whose work challenges, eludes, and inspires me in lyric and epic ways. I would also say any work in translation, which makes up only 3 percent of all publications in the United States.

6. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

Sustainable instead of survivable wages for the stewards of the arts—the program coordinators, the teachers, the editors, the publicists, the booksellers, the critics, the librarians—the people who bring this work into their communities, without whom these poems would remain private words on the page.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

The first draft of this manuscript elegized a relationship. But then my editor, Nicole Counts, helped me find how it was also about homes, which helped me understand how it was about me—the book within the book. I learned that every book I write is about me, no matter what I think about it.

8. How did you know when the book was finished?

When I can read it straight through without reaching for my pen. This is a fleeting window: As I change, what I want from my writing changes. So the other part of finishing is to let it finish.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

I rarely show single poems to others any longer. I know they are still cooking, so why serve the cake raw in the middle? I have a small group of friends who I turn to for full manuscripts. I will name one as an example, the Canadian writer Emma Healey, whose first book of essays comes out in April. I love Emma’s heart, her matrixed and tender intellect, and that we met in high school before any of this book business.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I think often of Toni Morrison saying that racism is a distraction. Evil is determined to convince me my life cannot be mine. It applies to so much else.