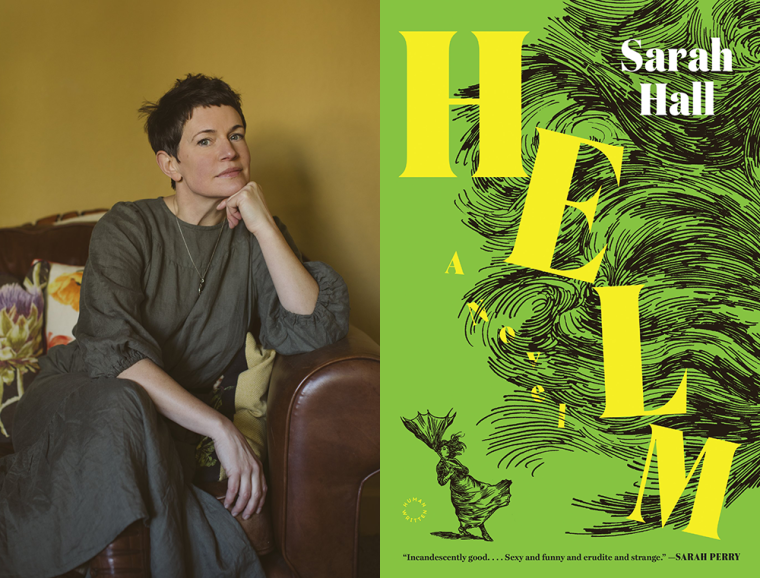

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Sarah Hall, whose novel Helm is out today from Mariner Books. There is just one wind in Britain with its own name: the Helm Wind of northern England, which rushes down the Pennine Hills and through Cumbria’s Eden Valley. Hall’s novel traces several millennia of human encounters with Helm, in stories that span a neolithic tribe worshipping the wind and a Victorian meteorologist trying to capture it with a steam-powered “Revelation Machine.” In the present day, the wind seems less formidable: A scientist counting airborne microplastics worries that pollution will destroy Helm. In the Financial Times, Luke Brown wrote that “the novel’s real strength lies in this view of a place through deep time…illuminating a location and a wider world through the continuities and discontinuities of the past.” Kirkus Reviews agreed in a starred review, calling Helm “an immense literary panorama.” Sarah Hall is the author of three short story collections and six other novels, including, most recently, Burntcoat (Custom House, 2021), a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction. Her writing has twice won the BBC National Short Story Award. Other accolades include two Booker Prize nominations; the E. M. Forster Award, administered by the American Academy of Arts and Letters; and the Edge Hill Short Story Prize. Born and raised in Cumbria, Hall now lives in Norwich, England.

Sarah Hall, author of Helm. (Credit: Kat Green)

1. How long did it take you to write Helm?

Twenty years, on and off. I sold the novel outline to my UK publisher around 2004 with a different title! (And subsequently delivered other books!) I couldn’t exactly figure out which stories to include and which not to. It was always going to be a sizeable and hopefully ambitious undertaking, but until I granted myself permission (or perhaps Helm grated it) to be free and unconventional and playful, and until I realised the central character was unstable and variable and that I had to embrace this mercuriality, I couldn’t make headway.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The structure was dementing—so many possibilities for interwoven tales and curation. The book’s chapters work a bit like spinning plates—narratives start up and keep turning while others are spun in, then they’re all going madly, until they begin to wind down and finish one by one. There are major stories and minor ones, vignettes, folk portraits, museum artifacts, and Helm’s voice holds the whole thing together, biographically. Some of the historical stories took me far out of my comfort zone, late Neolithic, Dark Ages, Victorian era—the novel has such a broad sweep of time it really challenged my range.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

For the last few years I’ve had a study, a new and grownup development as previously I’ve roamed around the house with my laptop. The room has painted yellow floorboards, strange art on the walls, and lots of plants—at heart I’m feral and like to imagine I’m working in woodland or a rainforest. I attend to projects most days. I’m always mulling about the latest or future work, even if I’m not actually writing or editing. I think the creative process is unboundaried. There are a lot of family commitments now that make it harder to sequester myself away and get words on the page, but this hopefully makes me more determined and efficient. The bottom line is I absolutely love what I do, so I keep doing it, no matter what.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m finishing Demon Copperhead (Harper, 2022) by Barbara Kingsolver and I’m starting a proof copy of Lara Feigal’s Custody: The Secret History of Mothers. Both are formidable writers.

5. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Helm?

That I could try to be—even, perhaps, achieve being—funny. Humour is a big part of my life and my friends would probably say I’m a bit of a goofball. But it hasn’t felt like my wheelhouse as a writer. With this novel, after a decade of personal loss and difficulty, and after several DEADLY SERIOUS NOVELS, I wanted to recover a sense of joy and child-like wonder at making things, to work with the idea of multiple creative possibilities. So while the subject of climate change is grave, Helm is silly, puckish, naughty, narcissistic, and curious, very entertained by the humans who are obsessing about Helm. Which I hope means the book is entertaining for readers too.

6. What is the earliest memory that you associate with the book?

Helm-spotting as a child. My parents’ cottage was next to a hill, from which Cross Fell mountain was visible, and I remember looking for the dramatic, signature cloud formation that meant the Helm wind was at large in the Eden valley.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

My agent uses the term ‘a big-swing book’ to describe it. I love that because it makes me feel I really put my energy into the thing and was ambitious and uninhibited. I’d rather try hard stretching to maximum creatively and fail, than write a squibby, safe, ‘little-swing book’...

My editor used the word ‘antic’ to describe Helm’s narrative during our conversations, and I wrote it in huge red letters and stuck it above my desk. It seemed so right for an aerial demon and set a great tone for the editing.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Helm, what would you say?

Wait. It’ll come when it comes. It’ll take a couple decades of climate breakdown news, and commitment to the discipline of honing short stories, and destruction of your sense of what a novel is, to get you ready for this one. And you’ll have to emerge giddy and ready out of the darkness.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Helm

Mothering. Climbing mountains. Getting very angry with politicians. Hanging out with environmentalists. Weather watching.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

“Sarah, why don’t you try writing in sentences.” This was said by my poetry tutor.