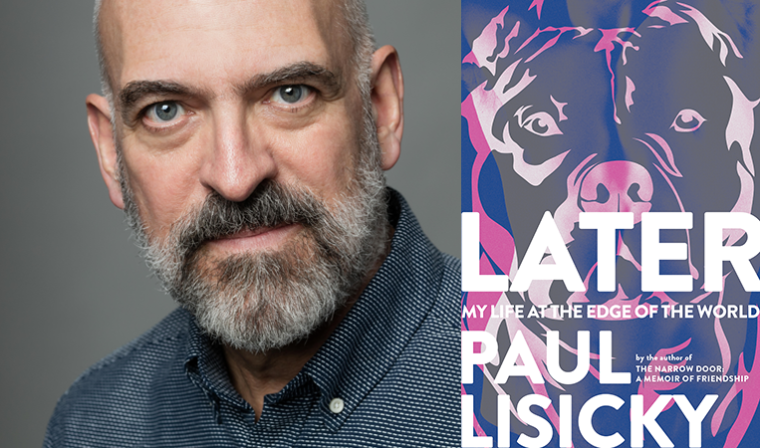

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Paul Lisicky, whose memoir Later: My Life at the Edge of the World is out today from Graywolf Press. Later opens in 1991 when Lisicky is packing up his car to move to Provincetown, Massachusetts. He arrives to a community consumed by the AIDS crisis, which takes hold in a different way than in America’s cities: “It’s not that anyone is less energetic about saving lives at the end of the world,” he writes. “It’s just that in a town that comports itself as a haven, where there’s no resistance from within, the desire to save lives take a different shape.” Weaving personal narrative with epigraphs and excerpts from queer artists across the ages, Lisicky traces this “different shape”—the unique structures of care, pain, and love that manifested in the Provincetown of the early nineties. At once intimate and expansive, Later is a vital exploration of queer life past, present, and future. Paul Lisicky is the author of five previous books including Unbuilt Projects (Four Way Books, 2012) and The Narrow Door: A Memoir of Friendship (Graywolf Press, 2016), which was a New York Times Editors’ Choice. His writing can be found in the Atlantic, BuzzFeed, Fence, Ploughshares, Tin House, and other outlets. A 2016 Guggenheim Fellow, he is also the recipient of awards from the National Endowment of the Arts and the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown. He lives in Brooklyn, New York and teaches in the MFA program at Rutgers University–Camden.

Paul Lisicky, author of Later: My Life at the Edge of the World. (Credit: Beowulf Sheehan)

1. How long did it take you to write Later?

It began as a novel all the way back in 1997, and I ended up showing it to others too soon, when I probably should have let it steep some more. In retrospect, I wonder whether it was a mistake to create a fictionalized version of an early 1990s Provincetown, when that place was already so much itself, without much of a comparison point. Which other small town, on the tip of a peninsula, took in people with HIV and AIDS, along with artists, people in recovery, people who refused to fit in?

I put the draft aside. Still, the urge to write about a community during a time of crisis never left me. I guess someone could argue that all my books since my first are attempts to capture this desire but through different people and objects and surfaces. Back in 2015 my father developed pneumonia. He went into hospice, was expected to die at any moment, recovered, went back home again. This happened over three cycles in six months. To put it simply, I felt emotionally pulled back into those early AIDS years again even though my father was old by that time and wasn’t HIV positive. A few weeks after he died, I started writing. I was the thinnest membrane and maybe that need to conjure up the community I once knew kept me going. The memory of that community, and its combination of affection, play, and turmoil, was company.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I could feel myself “processing” emotion in the early draft, which might be another way to say making certain moments a little too tidy, knowable, consoling, orderly. I don’t think those are necessarily problematic turns of feeling, but I think they should be questioned, especially if they start to feel reflexive. I wanted to write a book that made space for anger and disintegration, while also pointing to the kind of life force that that community summoned up on a collective level. So the trick was to find a form that embodied all of that. I started fragmenting the book, titling the individual sections, shifting it from past to present tense to create a deeper immediacy, on-the-spotness, which is certainly the way we lived those days. There wasn’t an overall plan back then. We had to be awake to emergency and disruption. How to write a book that behaved like that, in its structure?

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

All the time, honestly. I’m a lot less structured about my writing than I used to be, unless I have some extended time off, which is rare. My favorite place to write isn’t necessarily at home anymore—though I do write a lot at home, along with the coffee places in my neighborhood—but on a train or a plane or a subway. That sensation of rushing though time and space frees up my mind somehow. This must involve some early resistance about the act of writing requiring one to be pinned to a chair. I always admired any creative person who could literally move around as they worked: visual artists, actors, musicians. So if I’m not moving, at least the structure around me could move, damn it!

4. What are you reading right now?

I just finished Garth Greenwell’s Cleanness, which is as glorious as everybody says it is. Not just on the sentence level, but on what it has to say about shame. How do encounters with shame open up the constricted stories we tell about ourselves? I suspect I’ll keep going back to it for the rest of my life. I also just picked up Danez Smith’s Homie, and I’m very excited about the poems I’ve read so far.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

So many people. Anyone who writes books deserves wider recognition in this culture. I think there are people who don’t get talked about as much as they should because they’re not on social media, don’t have a web presence. I really love Salvatore Scibona’s work, for instance. He’s already been a National Book Award finalist, and that’s more recognition than most of us will ever get, but I think we should be talking more about his novels and stories, which are so impeccably written and intellectually present.

6. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

The early drafts of this book suppressed the character of the speaker, out of need to obscure myself and put the attention on the other people, whose experiences were much more precarious than mine. But my editor thought that the life in the book was with the speaker. The book needed a rudder, a guide. So she gave me permission to write a more vivid book than it had been.

7. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

If you feel like you need to be a part of a community to develop your work, to learn how to read like a writer, then yes. Definitely. Ideally the culture of an MFA should lead you toward thinking about why you write and how—that’s where vision develops. But sometimes all of that doesn’t happen for years after the MFA, and that’s okay. You might leave and think, That’s it? I’ve gotten grief, disrespect, and anxiety, and nothing else. But in truth an MFA gives you some tools. I think it’s up to you to decide whether you’re going to use those tools after you graduate. I mean I think my own work took off a year after finishing my MFA when I decided to write some work that I believed my workshop mates would have had very mixed feelings about. And I’m talking about particular writers whom I absolutely respected and adored. But I needed that point of resistance to say why and how I wanted to write.

But I’d never recommend pursing an MFA because you think you have to—no. I don’t believe in moving to a part of the country that you know you’re going to actively dislike, because that’s going to impede your work, your ability to be present. There are all sorts of rigorous online workshops that aren’t part of the degree-giving system.

8. What is one thing you might change about the writing community or publishing industry?

It definitely needs to be more inclusive on every level—we’re finally articulating that, insisting on it. At the same time, the prose world needs to be more democratized in terms of advances. The tactic of giving only a few literary books seven-figure advances and the rest next-to-nothing is toxic for writers and for the culture of books. A friend of mine who’s an editor in France is baffled by what the American publishing industry does.

9. Who is your most trusted reader of your work and why?

It’s my friend and former MFA classmate, Elizabeth McCracken. She and I write different kinds of work, but I’m always thinking of her as my primary reader. I don’t really show her my writing until it’s very close to finished—I’ve learned to keep my work to myself for a very long time—and she often doesn’t say chapter 3 belongs in place of chapter 2, but I want to write something that, well, knocks her out. I want to write to her standard.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Mark, my ex, and I were once driving down East 34th Street, and I pointed out a particularly styled poodle on the sidewalk and said something like: “The poodles of my childhood were unkempt.” He replied that that was an opening line, and I might have said, “Who would care about that?” Well, I ended up using that in a story in Unbuilt Projects, but the point was that he believed you should write what you need to write, not what you think editors and agents want. Work that’s good, that’s itself, eventually gets seen. Maybe not through the expected, gatekeeper-ish channels, but trust that it gets seen.