This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Nathan Go, whose debut novel, Forgiving Imelda Marcos, is out today from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. In this epistolary tale that spins an alternative history of the Philippines, an aging father, Lito Macaraeg, pens a letter to his journalist son in the United States about his experience working as the chauffeur to Corazon Aquino, who became the president of the Philippines in 1986 after leading an uprising against dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Macaraeg recalls his work for Aquino, including his drive to deliver her to a clandestine meeting with Imelda Marcos, the dictator’s wife. Lito’s own life story becomes interwoven with his narrative about Aquino and Imelda Marcos, spurring him to reflect on fatherhood, grief, and the way individual lives become inextricably linked to the sociopolitical context in which they find themselves. The book also serves as a poignant reminder of the United States’ former role as colonizer of the Philippines, where the aftermath of imperialism continues to unfold: “Yes, America is a liberator. But often it’s also a liberator from the problems it created in the first place,” Lito writes to his son. Kirkus praises Forgiving Imelda Marcos: “Go’s narrative burns slowly, gracing the novel with an understated yet profound power. A tender meditation on the unseen moments that shape history and the human spirit.” A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and the Helen Zell Writers’ Program at the University of Michigan, Nathan Go is a senior lecturer at the University of the Philippines in Mindanao. His fiction has appeared in Ploughshares, American Short Fiction, Ninth Letter, the Massachusetts Review, and elsewhere.

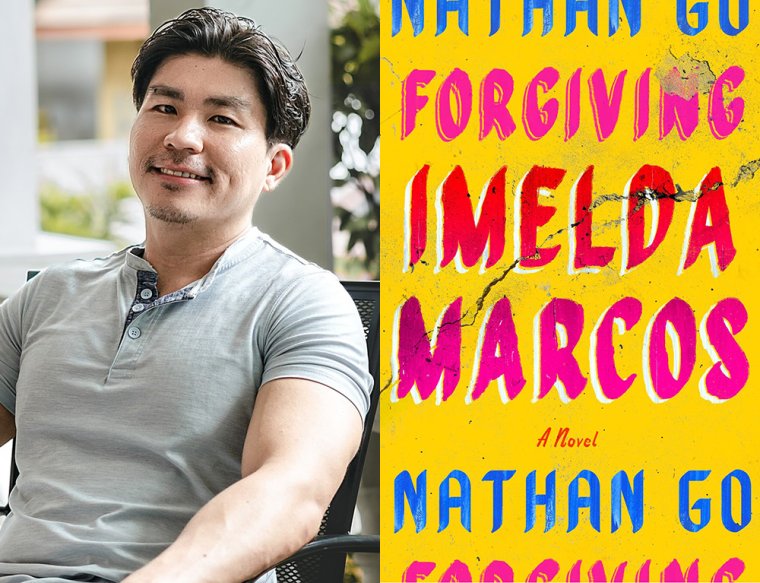

Nathan Go, author of Forgiving Imelda Marcos. (Credit: Crest Contrata)

1. How long did it take you to write Forgiving Imelda Marcos?

On and off, about fifteen years. I wrote the first draft as a screenplay for an undergraduate class in 2007. I forgot about it and picked it up again in 2014, when I turned it into a novella for my MFA thesis. Finally it became a novel around 2017 and underwent several more revisions.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I didn’t seek to write a political novel, but the characters in my novel happen to be political. While I was finishing the final draft, the political landscape in the Philippines kept shifting back and forth. For this reason I made a decision not to let current affairs influence my book—I stuck to seeing the story from my characters’ points-of-view as best I could. I know this novel will not make everyone happy. There will be those who want a stronger political message, and there will be those who want a less political message. I just let my characters decide where the novel would go.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

My ideal writing schedule, which I achieved only once in my life—during my David T. K. Wong Creative Writing Fellowship at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, (for which I am eternally grateful!)—is to write as soon as I get up for about two to three hours, go to the gym, have lunch, and take a light nap. Then I would wake up and write for another two to three hours before going to the gym again and having dinner and a bath. I would read for the rest of the night before falling asleep and repeat the same routine the next day. Physical activity leads to better sleep, and better sleep leads to better dreaming, and better dreaming leads to better writing. I believe that writing is just a form of dreaming.

4. What are you reading right now?

I have a lot of catching up to do: In West Mills by De’Shawn Charles Winslow; Letters to a Writer of Color, edited by Deepa Anappara and Taymour Soomro; Brotherless Night by V. V. Ganeshananthan; and the Boxer Codex, a sixteenth century manuscript about the Philippines compiled by European imperialists for the King of Spain.

5. Which author or authors have been influential for you, in your writing of this book in particular or as a writer in general?

Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead and Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day were always on my table when I wrote the novel. In general, I am much indebted to Paul Harding and Margot Livesey, who really taught me not just how to write but how to be a generous writer.

6. What is one thing that surprised you during the writing of Forgiving Imelda Marcos?

How polarizing the title became because of the Marcoses’ big comeback in the Philippines. Again, I did not seek to write a political novel. Since the first draft in 2007, when the Marcoses were pretty much on the down-low, the title has been Forgiving Imelda Marcos. That was simply the most intuitive title: It was what I imagined the character Mrs. Aquino, a devout Catholic, contemplated during the last days of her life. I was not trying to make any political statement at all with the title.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

There wasn’t one thing that my agent or editor told me that stuck with me. Rather, I was more surprised at how long the publishing process took even after I sold the book. The novel had gestated for fifteen years and underwent so many revisions that I hadn’t expected my editor to do several more rounds of revisions. But they were all very helpful, and Farrar, Straus and Giroux was very supportive. I ended up rather happy, and humbled.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Forgiving Imelda Marcos, what would you say?

Perhaps write a different novel.

9. What forms of work, other than writing, did you have to do to complete this book?

I was a student, for the most part, when I wrote the different versions of the story. But when I went back to the Philippines and started helping out with my family business, I became extremely busy and forgot about the novel. It was only during the pandemic, when my family and I found ourselves stuck in Atlanta while on vacation, that I suddenly had time to revise the novel and send it to an agent.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

All rules of writing are there to be broken. Otherwise, if we just simply follow all the rules, it’s not art: It’s ChatGPT, or artificial intelligence (AI). The paradox is that while we’re still learning to write, we do have to learn the rules. Only then can we become good enough to break them and form our own rules. I wonder if that’s what would differentiate human writers from AI.