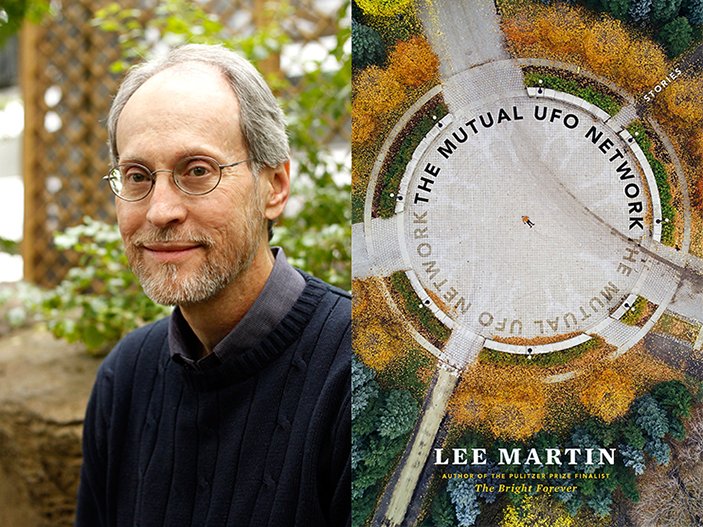

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Lee Martin, whose new book, The Mutual UFO Network, published today by Dzanc Books, “explores the intricacies of relationships and the possibility for redemption in even the most complex misfits and loners.” It is his first story collection since his acclaimed debut, The Least You Need to Know, was published by Sarabande Books in 1996. Martin is also the author of three memoirs as well as the novels Quakertown (Penguin, 2001); The Bright Forever (Shaye Areheart, 2005), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction; River of Heaven (Shaye Areheart, 2008); Break the Skin (Crown, 2011); and Late One Night (Dzanc, 2015). He teaches in the MFA program at Ohio State University.

Lee Martin, author of The Mutual UFO Network.

1. How long did it take you to write The Mutual UFO Network?

The earliest story in this collection was published in 1997, and the last one appeared in 2014. In the time since my first collection came out in 1996, I’ve published five novels, three memoirs, and a craft book, but I’ve also kept writing stories. There were times in that gap between 1996 and now when we could have tried to bring out a new collection, but I’m glad we waited until the book was truly a book rather than merely a random gathering of stories.

2. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’m a morning writer, and I normally work in my writing room at home, sometimes with my senior editor, Stella the Cat, on my lap. She has claws, and she holds me to task. Lately, though, I’ve discovered another writing space. My wife works remotely for a hospital in our home area of southeastern Illinois. She has to be onsite four days out of each month, and, when I can, I go with her. I end up writing in the small public library I used when I was in high school. It pleases me to know I’m writing in a place where I once read so many other people’s books and dreamed of one day having a book of my own. Sometimes people stop by and tell me stories, and sometimes I use them. I try to write at least five days a week. I used to write every day, but, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve become more comfortable with rest and the way it can re-energize me. For the most part, we writers are introverts, and it can become easy to withdraw from the world. I’m lucky enough to be married to an extrovert, and the weekend is now our time to engage with life outside the writing space.

3. What was the most surprising thing about the publication process?

That I ever got published at all! Seriously, when I was starting out, I gathered so many rejections, I started to believe that door would never open for me. I couldn’t stop writing, though. It’s what gave me pleasure, and I knew even if I never got published, I’d still love moving words around on the page. That’s why I tell my students to keep doing what they love as long as they love it. As I began to publish books, I learned so much about the part of the process that doesn’t involve writing or editing. I’m talking about the behind-the-scenes work of publicity and marketing. Everything from how the sales reps work to cover design. I’m still amazed by the decisions that get made that can make or break a book before it even hits the shelves.

4. Where did you first get published?

I published my first story in 1987 in the literary journal Sonora Review. My first collection, The Least You Need to Know, was the first winner of the Mary McCarthy Prize from Sarabande Books, and it came out in 1996.

5. What are you reading right now?

I just finished a fascinating memoir by David Giffels called Furnishing Eternity. It’s about the author’s desire to build his own casket even though he has no immediate need for it. His aged father, an accomplished woodworker, sets out to help him. That’s the narrative spine, but the book is about so much more. With wit and warmth, Giffels explores aging and death and family and friendship. It’s a beautifully written book with not a trace of sentimentality.

6. If you were stuck on a desert island, which book would you want with you?

In our family room, there’s a length of an old door casing that my wife and I rescued from the debris of the farmhouse where my family lived when I was young. My wife turned it into this shelf, and we put old family photos and mementos on it. My mother was a teacher, and one of the things she left behind was the school bell she rang at the old country schools where she once taught. That bell sits on top of two books, To Kill a Mockingbird and The Great Gatsby. If I had to choose one to have with me on that desert island, it would probably be Gatsby. I reread it each year with continued admiration. I guess I’m a romantic at heart. The story of Daisy and Gatsby gets me every time.

7. Who is the most underrated author, in your opinion?

I’ve had the privilege of knowing a number of writers who would fall into that category. I’ve met them through their books, and sometimes I’ve been lucky enough to know them personally and to be able to call them my friends. I’m not trying to avoid the question. I’m only honestly stating the fact. I imagine there are literally thousands of writers who should be appreciated more than they are. These writers are doing work just as memorable and just as necessary as the big-name folks, but for whatever reason they haven’t broken out the way their more famous counterparts have.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

I once told someone that any writer would gladly trade money for time. I’m not sure that’s true, but it feels true from where I sit. I’m a writer who has a hard time saying no to people, so I sometimes find my writing time being reduced due to things I’ve promised other writers, or my students, that I’ll do. I think of all the favors others did for me when I was just starting out—blurbs, letters of recommendation, etc.—and I try my best to keep giving back to the profession. As the years have gone on, I’ve begun to feel a slightly different pressure, and that’s the threat that comes from our “connected culture.” The internet, social media, e-mail, texts—they all demand that we always be available, and, if we let them, they can destroy the solitude and quiet writers need to immerse themselves fully in their work.

9. What trait do you most value in your editor or agent?

I like an editor and an agent who will tell me the truth about a manuscript, no matter how painful it may be for me to hear it. I like them to understand what I’m trying to accomplish and to be able to offer honest, but tactful, suggestions for what I need to do to fully realize my intentions. So honesty, insight, a collaborative spirit, a supportive presence, and, finally, a willingness to be a tireless champion of my work.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I see so many young writers who want to succeed immediately. They want to publish, they want to win awards, they want validation. In their desperation to attain that validation, they sometimes forget why they love to write. In every workshop I teach, I pass along a single piece of writing advice. It comes from Isak Dinesen who encouraged writers to, “Write a little every day, without hope, without despair.” We all fall prey to both hope and despair from time to time. Both seduce us into thinking about the end result of the work, and, consequently, we don’t pay attention to the process. If we can write a little with some degree of consistency and without agonizing over how good it will be, who will want to read it and praise it, etc., we can remember how much we love the mere act of putting words on the page. To be in the midst of that love is a wonderful thing. I’m firmly convinced that if we pay attention to the process, our journey will take us where we’re meant to be.