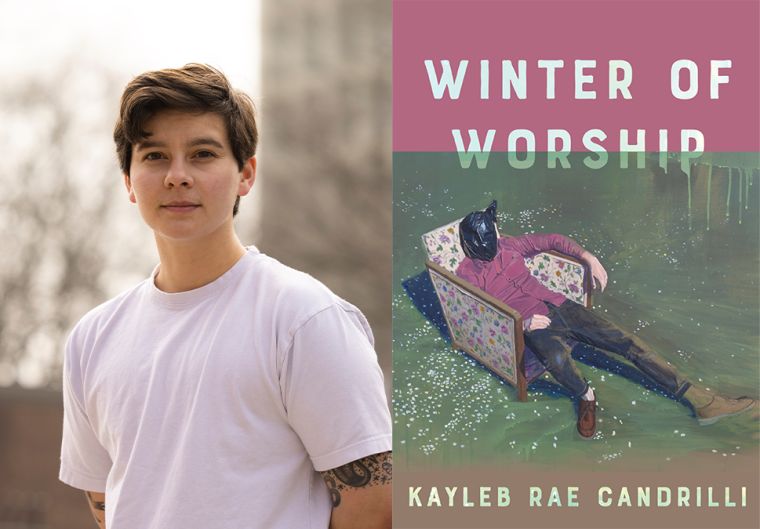

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Kayleb Rae Candrilli, whose fourth collection, Winter of Worship, is out today from Copper Canyon Press. The collection is told through an ever-queer lens and explores both the pastoral and the “litter swirled around us”—a pandemic, global warming, a hometown hit by storms of fentanyl and Oxycontin scripts. The elegiac poems are written in a variety of forms and reckon with loss: of climate, of fathers, of youth. The collection also traverses a wide geography: from downtown Brooklyn to the cornfields of Pennsylvania. The Los Angeles Review of Books said, “Candrilli’s poems skillfully delve into—amid much else—what it means to be alive on this damaged earth. They precisely interrogate what happens when human interactions poison—or ‘touch’—something formerly unadulterated.” Kayleb Rae Candrilli is a 2019 Whiting Award Winner in poetry and the author of Water I Won’t Touch (Copper Canyon Press, 2021), All the Gay Saints (Saturnalia, 2020), and What Runs Over (YesYes Books, 2017). Candrilli was a 2017 finalist for the Lambda Literary Award in transgender poetry and a 2017 finalist for the American Book Fest’s Best Book Award in LGBTQ Non-Fiction. They live in Philadelphia with their partner.

Kayleb Rae Candrilli, author of Winter of Worship. (Credit: Ryan Collerd)

1. How long did it take you to write Winter of Worship?

The poems of Winter of Worship were written between 2018 and 2024, so six years of writing poems! The lion’s share of turning the poems into a book took place in 2022 at the Carolyn Moore Writing Residency, where I was lucky enough to be in residence for the month of April. Lucky enough, too, to be in residence alongside Diannely Antigua, who was so generous and helpful. Check out Diannely’s second book, Good Monster.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

The most challenging aspect of writing Winter of Worship was being forced to examine grief so closely for such extended periods of time. The book is in large part a work of elegy, and I often found it taxing to live in that yearning for the dead. That said, I know that’s what was best for both me and the poems.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write extremely infrequently as of late. I tend toward writing in spurts, so I anticipate months of inactivity between the short periods of productivity. Though, a typical spurt of drafting for me often results in quite a few poems.

Moving forward, I would like to introduce prose writing into my life and career. I anticipate a much different writing practice will reveal itself to me when working more narratively.

4. What are you reading right now?

I am thrilled to be reading Santiago Jose Sanchez’s debut novel, Hombrecito (Riverhead, 2024), which is so tender and perfect and queer. I’m also reading Anne Rice’s The Vampire Chronicles, which I can’t believe I didn’t read sooner. I’m an unabashed fang enthusiast!

For my YA fix, I’m so enjoying the Wayward Children series by Seanan McGuire. Lastly, I keep returning to Hafiz by Sabiha Çimen (Red Hook Publishing, 2021), which is one of the best photo collections I’ve ever had the pleasure to experience.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Though the recognition, I’m sure, is already well on its way, I’d love to take this opportunity to plug Spencer Williams’s debut poetry collection TRANZ, which was published this past September by Four Way Books. I’m just obsessed with her work and haven’t taken TRANZ off my bedside table since its release.

6. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

I have a relatively methodical way of organizing my books; Winter of Worship was no exception!

I start by running my manuscript through a word-cloud generator. Though often demoralizing to see one’s linguistic patterns laid so bare, I find word-clouds helpful in pulling the book’s obsessions into focus. Subsequently, I translate the word-cloud into color-coded groupings. For instance: Water, oceans, lakes, and landscapes will be assigned blue. And so on. And so on.

Next, as I read through the book, I tag the top right of each page with the colors that thematically correspond to the poem, in a hierarchical order. After I’ve tagged every page, I lay the poems on the floor.

It’s in this stage that I’m able to see where I’ve “clumped” thematically similar poems too tightly together, or where I’ve gone too long without a poem that contains a main prong or tenet of the project. It’s also in this stage where you might find thematic stragglers that don’t belong in the project at all. I rinse and repeat this process until I feel the book is indeed a book!

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

I don’t know that I can identify a single moment as more poignant than the whole, but working with Ash Wynter of Copper Canyon was a total gift, start to finish—so smart, kind, patient, and invested in realizing the book’s vision. The funny answer, though, is I had been using the word arid incorrectly for my whole life and finally Ash came to my rescue!

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started Winter of Worship, what would you say?

I don’t have an answer specific to Winter of Worship, but if I could go back and speak to a younger version of myself, I might advise I pace myself a little more in terms of seeking publication. I might tell myself what I know now, that writing isn’t a race.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of Winter of Worship?

This is not so different than any other project, but music played a large role in the book’s creation—particularly the music I listened to most in the late oughts and early 2010s (think Gaga, Kid Cudi, Mac Miller, etc). Winter of Worship is a nostalgic book, and what better way to conjure nostalgia than through music.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I can’t remember when or where I was when I heard Mahogany L. Browne talk about daily writing practice. But her gist was to be more liberal in what you consider writing. Your e-mails are daily writings. Your grocery lists; your text messages; your poetry magnets on the fridge; your annotations in the margins of your books. Everything you read is part of your daily writing practice. Every photo-book cracked. Every video game played. Every album spun. Every film watched. All art you ever have or will consume is part of your writing practice.