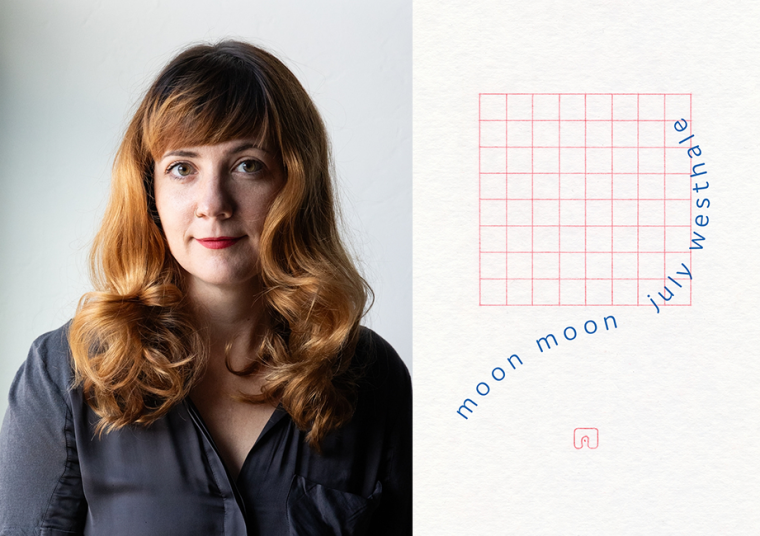

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features July Westhale, whose poetry collection moon moon is out today from Black Lawrence Press. In the style of epic poems like Gilgamesh and The Odyssey, moon moon applies a formal approach to what is truly unimaginable: speculation of the world’s end, and the spectrum of possible conquests to follow. In this collection Westhale includes poems that are rife with eco-grief and undercut with dark humor and strangeness. Readers journey from the world to the moon, to the moon of the moon, and back again—sometimes scientifically, often experientially, and always obsessively. Bob Hicok says, “July Westhale’s work has an investigative and improvisational quality that makes moon moon an endless surprise. Reading this book is like opening a homunculus that never ends.” July Westhale was born in the American Southwest. Their books include Trailer Trash (Kore Press, 2018), Unmade Hearts: My Sor Juana (Small Harbor Publishing, 2024), and Via Negativa (Kore Press, 2020), which Publishers Weekly called “stunning” in a starred review. Ocean Vuong chose Westhale as the 2018 University of Arizona Poetry Center Fellow. They have work in McSweeney’s, Diagram, the National Poetry Review, Prairie Schooner, and the Huffington Post, among others. Westhale lives in Tucson, where they are adapting their novel to film.

July Westhale, author of moon moon. (Credit: Rachel Marie Photography)

1. How long did it take you to write moon moon?

It took me about two months to write moon moon. It was written during lockdown, when there was a good deal of empty space, coupled with a sense that nothing would ever be quite the same again. It was the ideal scenario for someone to compose a modern, slightly science-fictiony book of poems that is also about the world possibly becoming uninhabitable.

I’m a fast writer and a slow editor. I spend much more time editing than ideating, and then I put my work up on a wall to see where I still need more volume or shape or where the gaps are. Then I write some more, edit some more. And on and on. One of the many wonderful things about working on moon moon specifically was creating a world and a book-length narrative for the first time in my poetry; it’s a story that follows the structure of an epic. I had some guardrails, but I got to be as imaginative as I wanted, and I got to expand the way I thought about writing poetry.

And while it is an expansive, strange book, it manages to feel contained and possible. I think that’s in part because it was written from a place of confinement. It was written while the entire world felt quiet and small.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I’d say it was figuring out where to stick to the form of a traditional epic and where to abandon it for the sake of the poem’s content. Ultimately, I wanted moon moon to be recognizable as an epic, but I also wanted to experiment in the same way the content experiments with the concept of habitable worlds.

This is a challenge I’ve mostly encountered while doing poetry translation, so it was novel to apply it in this process. Like all challenges, it gave me opportunities to be thoughtful about the moments I was breaking form in order to go on a wild ride with a poem. It had to be intentional; it had to be for effect.

Sometimes I neglected to add something—epics have a lot of moving parts!—so I just admitted it. And it’s fun—for example, oops, I forgot about hell. I would say something like “insert a trip to the underworld.” Again, as in literary translation, this admission is common, often by way of footnote or translator’s note, and I was enamored with the intimacy of it. How it showed the seams.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I can write anywhere, and have, but these days I mostly write from exactly where I am at this moment: my home office in Tucson, with my little black cat on my lap, a giant bougainvilla outside the window. I write whenever I can. That’s sometimes on my lunch break from the job that pays my bills, or early in the morning before work, or on the weekends, or on trips. My brain is best in the morning, but I’ve learned to take the time I can get.

It’s common for me—across genres!—to write in prolific jags and to work on a number of projects at the same time. I write poetry, but I also write fiction, and, as mentioned, I do literary translation. I’m trying to be a screenwriter, but I’m not very good at it. I’m currently adapting my novel. I’m doing this in collaboration with LA-based screenwriter Gregg Jaffe, and nonfiction writer and poet Em Bowen, who is also my partner in life.

Of course, then there’s the writing you do to stay connected to the world and be of service: interviews with other writers, book reviews, blurbs, and on and on. I want to be a person who generously says yes to these requests when people are brave enough to ask them, and so I am.

4. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Leif Enger’s I Cheerfully Refuse (Grove Press, 2024). It’s wonderful and bonkers. I’m not sure how it manages, but it is all at once sweet, apocalyptic, an expansive tale of adventure, and dystopian without being too terrible to bear. This is my first time reading Enger’s books, and I hope they are all this terrific. Please say yes.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I think she’s starting to come into a larger audience but...last year I fell into a pit of Tessa Hadley’s making. I’d read one of her short stories in the New Yorker and I immediately checked out everything I could find at the library. If you are also just discovering her work, you’re in luck—she’s prolific. She’s a particularly masterful short story writer. Sunstroke (Picador, 2007) and Bad Dreams (Harper, 2017) are wonderful, but you can’t go wrong with any of her collections. Her novel Late in the Day (Harper, 2019) knocked me out and was one of the best things I read last year. She’s idiosyncratic and funny and moving. I can’t get enough of her.

6. What was your strategy for organizing the poems in this collection?

When I decided that this would be a modern epic, I graphed out the narrative arcs and characteristics of a few I admired, focusing mostly on Gilgamesh. Graphing is something I tend to do when writing fiction, and I’d never used it as a strategy for organizing or writing a book of poems before. It ended up working well. I allowed the form to break when it felt intuitive to do so, and I let the sections be uneven as a way of correlating to the level of surreality of the setting.

The book has three parts—in part one, the humans discover they can no longer live on the Earth, that it has become uninhabitable, and so they decide to go to the moon. The section ends with them realizing the moon is full. They reroute instead to the moon’s moon. The second section is about their settlement on the moon’s moon, about how they start to believe they have become gods. It gets weirder and weirder. The third section is a surprise—I’ll let you find that one out for yourself.

I should also mention that a moon’s moon may or may not be the astronomically accurate way of describing a moon that orbits another moon, or anything that orbits another moon. It can even be a rock. Or trash. Space trash. I really fell in love with the idea of the moon’s moon as a kind of...bargain basement Ramada.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

So many things! I’m lucky. Diane Goettel is one of the most operationally sophisticated humans I’ve ever had the pleasure of working with. Everyone should get the opportunity to work with a publisher who is as thoughtful, concise, and organized as Diane. One of the first things she said to me about moon moon had to do with the reason she decided to publish it. There’s a line in one of the poems where the humans/gods are in space, and they miss trash because trash could be thrown away. When Diane wrote to me and told me she particularly loved this idea, I immediately knew I had brought my weird little book to the right place; this collection is about many things, but one of the things at the very center of it is human earnestness and sentimentality. With her keen eye she saw that instantly.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started moon moon, what would you say?

Well, you know, there are so many things I’d say to the 2020 version of me! One thing I would say in advance of writing moon moon is that a modern epic that is also about the grief of climate change is only going to become more and more relevant. This book lands more sharply now than it would have if it came out five years ago, and perhaps it would have even more resonance if it came out in 2028, or 2040. But as imaginative as we can be, as much as we can speculate, we can never quite capture how things will be, the size of change, or our capacity for bearing it.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of moon moon?

I could not have written moon moon without the following: Erik Satie’s Gymnopédies & Gnossiennes, the complete piano etudes of Philip Glass, and the movies The Neverending Story and Dracula (with Bela Lugosi). I also had it in my head that the Oracles at the entrance of the moon’s moon would be different versions of Whitney Houston, so I rewatched a fair number of her films. Again, you’ll have to read the book to find out where I landed.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I was once in a workshop with Carl Phillips, who managed to say many things that stuck over the course of four or five days. One thing he said is that if you are writing consistently over a period of time—say you’re writing every day for a month or every few days for a few months, or every week for a year—you will not necessarily need to impose a theme onto your work. The work will emerge with its own themes, because the things you are mulling over and working through during that time in your life will continue to show up, and the poems will “talk” to one another.

What a relaxing thought! As a person who has never really had any control over what my books are “about” it was great to know, in my interpretation of Carl’s words, that I didn’t actually need to worry about it terribly much. This advice has also helped me to write consistently, as a way of being in service of whatever theme is there, laying in wait for me.