This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Joshua Wheeler, whose debut novel, The High Heaven, is out today from Graywolf Press. It’s 1967, and two real-life space missions have gone wrong: In Florida, NASA’s Apollo 1 has caught fire during a launch rehearsal, killing three astronauts, and in New Mexico, a UFO-worshipping Christian cult trying to resurrect a corpse has run afoul of the government. Out of the wreckage emerges Izzy, a child spouting garbled Bible verse and carrying a Galaxy radio she is convinced transmits messages from God. In a three-act structure that pays tribute to Western, picaresque, and Southern Gothic genre conventions, The High Heaven charts the trajectory of Izzy’s restless life and the shifting American visions of space and salvation that guide her way. Fernando A. Flores described the novel as “Dickens dropping acid in the desert of 1960s New Mexico, having visions of outer space and America that may be of the past, present, or future, but that, under the spell of Joshua Wheeler’s poetic sentences, fuse into an act of supreme imagination.” Joshua Wheeler is the author of the essay collection Acid West (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), named a best book of 2018 by Newsweek, the Paris Review, and O, The Oprah Magazine. He’s written for the New York Times, Alta, and Harper’s Magazine. He teaches at Louisiana State University.

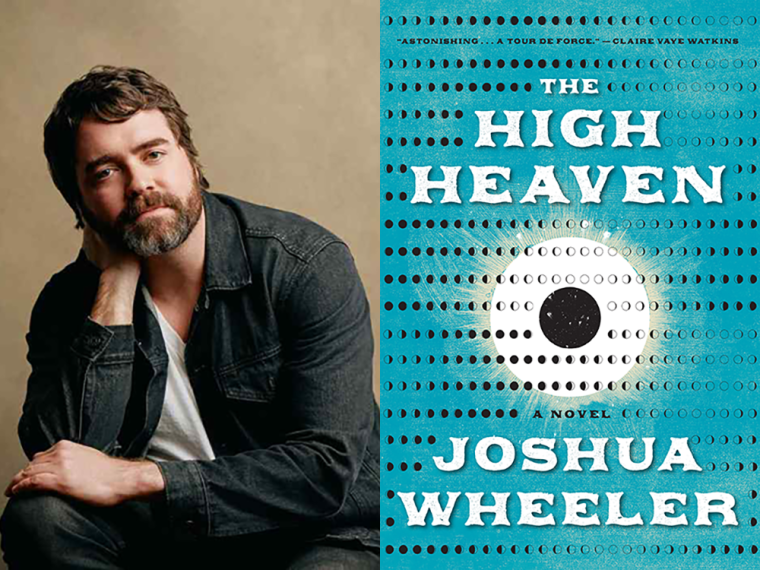

Joshua Wheeler, author of The High Heaven.

1. How long did it take you to write The High Heaven?

I guess The High Heaven emerged between total solar eclipses. It was composed roughly from the Great American Eclipse of 2017 to the Great North American Eclipse of 2024. But, until the Great Pandemic of 2020, I was mostly just pondering the book’s big ideas about faith and technology. After that, there were maybe 64 full moons of the real and true labor of writing, two of which were blue moons.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

One project of the book from the outset was to tell this woman’s life across three distinct geographies, three distinct genres, three distinct stages of her life. So the challenge was how to create that triptych without it feeling like three totally different books. I also wanted to start fairly far removed from her point of view when she’s young, then slowly, as she ages, draw closer to her consciousness until we’re fully in the stream of it when she’s old. That was kinda tricky. And then there’s the celestial stuff, like the Metonic cycle, that structures a lot of the book. Tracking the moon’s phases and sky placement from 1947 to 2024 got to be a real headache. Which maybe explains why, in the book’s third part, some characters lose the ability to see the moon. Maybe I got mad at the moon and wrote it away.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write at home mostly, though I guess a good portion of this book I wrote on a tiny mattress in the bed of my truck while camping and riding bikes across Texas. But at home, which is a shotgun house in New Orleans, I have desks of varying heights by every window so I can daily follow the sunlight, which is vital for the photosynthesis of sentences. If I’m locked in on a thing, I write all day. But other times I don’t write for months. I tend to always be pondering, though.

4. What are you reading right now?

The stack of books really making me happy right now is all recent stuff by former students. Scavengers by Kathleen Boland, a kind of Western-scavenger-hunt comedy, out early next year from Viking. God-Disease, a collection of creepy-smart Korean horror stories by an chang joon. The Flat Woman by Vanessa Saunders, a wild and weird novel where women are blamed for the climate crises. Beautiful poetry by Ian Lockaby, Defensible Space/if a crow—. And a great true crime memoir set on the Cajun prairie, Home of the Happy by Jordan LaHaye Fontenot.

5. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I can’t get enough Christina Rivera Garza lately.

6. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

The greatest threat to any writing life, not to mention just plain old regular life, is fascism. The pursuit of art and the pursuit of truth shouldn’t have to be revolutionary acts. But these days too often they feel that way.

7. What is one thing that your agent or editor told you during the process of publishing this book that stuck with you?

I had the great good fortune of being edited by Carmen Giménez, who is a brilliant literary mind, from poet to essayist to publisher. Working with her changed the way I think about making books. At one point she started referring to The High Heaven as a folk tale, and to Izzy Gently, the protagonist, as a sort of folk hero. That changed my approach to editing the book in the best way. After that, I was just channeling all the old stories.

8. If you could go back in time and talk to the earlier you, before you started The High Heaven, what would you say?

It should be possible to both write good and live good. Go see your friends. Be with your family. Taste something new. Fall in love with the world again and again while you still can.

9. Outside of writing, what other forms of work were essential to the creation of The High Heaven?

Well, I had to build all those desks I write at. The standing desk is made from an old New Mexico ranch door plus galvanized pipe. The middle-height desk is reclaimed wood from a big flood in Denham Springs, Louisiana in 2016. The sitting desk is a vintage dining table I fixed up and refinished and built some leaves for because it is impossible to find walnut leaves for a Lane Acclaim dining table from the late sixties.

Also, in 2022, I rode my bike across Texas along the future path of totality for the 2024 solar eclipse, which features in the novel. That’s when I was often camping, sleeping in my truck. It didn’t feel like work, but I probably deducted camping fees on my taxes. And I found lots of strange parts of Texas that seeped into the novel.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

Harry Crews supposedly said write naked, meaning like get to the flesh of the truth, the bone of the truth, even. Ursula K LeGuin said write like who you are, which is, I think, distinct from the cliché advice of write what you know. I think about those two things often. But also really I think it’s all about sentences. DeLillo said something like he never quite figured out how to write a good novel until he figured out how to write a good sentence with the right rhythm, and that’s true in my experience. Everything I know about what to write comes from trying to understand the music of what I’ve got to say.