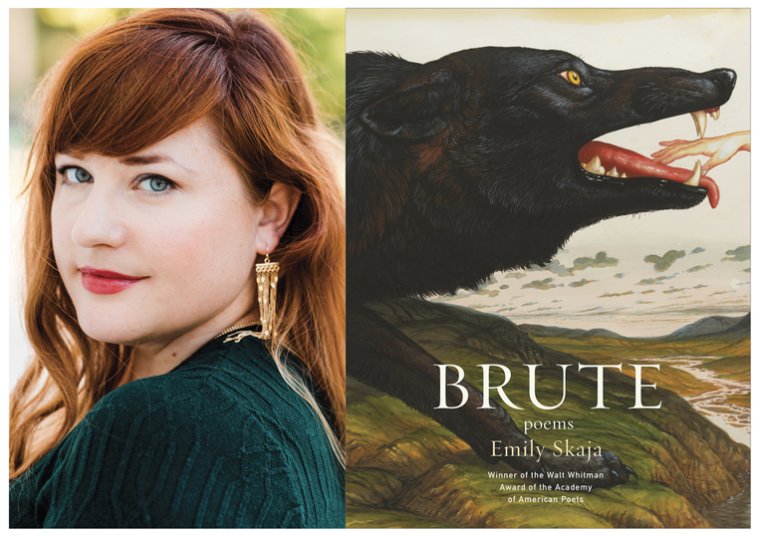

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Emily Skaja, whose debut poetry collection, Brute, is out today from Graywolf Press. The winner of the 2018 Walt Whitman Award from the Academy of American Poets—an annual prize for a first book of poems that includes $5,000, publication, and a six-week residency at the Civitella Ranieri Foundation in Umbria, Italy—Skaja’s debut is an elegy to the end of a relationship that confronts love, loss, violence, grief, and rage. “What do we do with brokenness?” asks prize judge Joy Harjo, who selected the winning manuscript. “We document it, as Skaja has done in Brute. We sing of the brokenness as we emerge from it. We sing the holy objects, the white moths that fly from our mouths, and we stand with the new, wet earth that has been created with our terrible songs.” Emily Skaja grew up in rural Illinois and is a graduate of the MFA program at Purdue University. Her poems have been published in Best New Poets, Blackbird, Crazyhorse, FIELD, and Gulf Coast. She lives in Memphis.

Emily Skaja, author of Brute. (Credit: Kaitlyn Stoddard Photography)

1. How long did it take you to write Brute?

Five years. I started writing the poems in Brute in 2012. About three years into it, I had a book-length manuscript, but it felt incomplete to me. I wound up cutting or revising more than half of it, and then I spent another two years rethinking, rewriting, and rearranging it before I fully understood what shape it should take. In that time, I changed so much as a person that the manuscript began to feel closed off to me. Trying to write back into it was like being in conversation with a ghost of myself—a voice that draped itself in my clothes and spoke about my experiences, but from the point of view of someone who was a few steps removed from me. I found that in order to keep working on the book, I had to write my way back into it in a way that honored the time and distance that separated the new self from the ghost. As a result, there are a lot of poems in the book in which I address my younger self and try to reassemble her memories with the wisdom of recovery.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

There’s a lot of mystery in my writing process, and I have the suspicion that I’m doing all the steps out of order. At the outset, I never know where any project is going. I start with a pile of drafts and look for signs of my own obsessions, and then I try to understand why I keep returning to a particular idea, feeling, or image. No matter how many times I reassure myself that I am, in fact, in charge of this process, I always feel as if I’m the last person to understand what I’m writing toward. It’s only in revision that I can see how consistently I’ve written about a particular idea, and then I can revise and cut and rework the poems as needed. Writing Brute was a painful process of self-discovery because my analysis of the obsessions in the manuscript required me to address parts of myself and my past that still felt raw. Initially, I believed that I was just writing a series of sad love poems, and then about halfway through drafting the book I realized that I was writing about grief and power and self-abandonment and rage. The poems are about my own experiences with abusive relationships, so changing my mind about the book also meant changing my mind about my life, and that proved to be very difficult.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write late at night at a big table I once painted bright orange during some heady HGTV-evangelist period of my life. I go through irregular seasons of writing. Something will trigger a writing cycle and I will work on fifteen poems in a row, and then I’ll experience a long, fallow period where I have no impulse to write at all. My strategy is to feed the fallow period with heavy reading. I try to be patient with myself when I’m not writing, but I’m much less forgiving if I’m behind on reading.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

The most surprising and gratifying part so far has been gaining a community of sympathetic readers. For a long time, I was writing these poems from a place of shame, so it has meant so much to me to hear from other people who have shared the same experiences or felt an emotional resonance with these poems.

5. What are you reading right now?

I’m reading Notes to Self by Emilie Pine, The Far Field by Madhuri Vijay, Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky, and Build Yourself a Boat by Camonghne Felix. I recently finished Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls by T Kira Madden, which I loved so much I know I will read it a second time. I also loved The Water Cure by Sophie Mackintosh and Milkman by Anna Burns.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Ingrid Rojas Contreras, whose brilliant essay “All Good Science Fiction Begins This Way” I have admired and taught for years, and who recently published a novel I also loved, Fruit of the Drunken Tree.

7. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

I would like to see more widespread initiatives to support writers of color, especially women and nonbinary writers.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing process?

I think my own brain is my worst impediment. I spend a few hours every day so consumed by dread that I can’t make myself do anything, so I sometimes daydream about all the amazing projects I could finish if I could reallocate those dread hours.

9. What trait do you most value in an editor?

I love to work with editors who can look at a line or a poem that isn’t quite right and help investigate what its curiosities are or what ideas it’s trying to find its way into.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

The wonderful Don Platt once advised me to “go hard into the weird and stay there.”