Toni Morrison’s editorial career at Random House in the 1970s and early 1980s remains a profound and often underappreciated chapter of literary history. We speak of her as a novelist, a Nobel laureate, a literary giant—as we should. But Morrison’s years as an editor at Random House reveal another side of her genius: the deliberate ways she created space for Black women writers, poets in particular, to be fully seen, even at a time when publishing poetry was a financial risk few houses would take on.

Toni Morrison photographed in New York City in 1979. (Credit: Jack Mitchell via Getty Images)

Publishing Black women poets at a major house was not just an editorial choice—it was a political act, a cultural investment, and a quiet revolution. The three poets whose work she helped bring into print could not have been more distinct. Barbara Chase-Riboud was a sculptor turned poet, largely unknown in literary circles before Morrison took a chance on her verse. Lucille Clifton was an established poet when Morrison inherited her work from a departing editor, but we can see Morrison’s gentle hand in helping Clifton grow as a poet. June Jordan was a celebrated writer who had not previously published with Random House. Morrison’s recruitment of Jordan to her roster signaled Morrison’s belief that poetry, too, must have a place in the evolving canon of Black literature.

There is something deeply moving about the way Morrison made room for poetry written by Black women—in a space that wasn’t designed with them in mind. She did more than just publish their work. She honored it, nurtured it, and placed it on shelves where we could find it and read it for ourselves.

The following is adapted from a chapter of Toni at Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship, published by Amistad in June.

Dear Barbara,

I astounded myself by getting some overwhelming support for your book at sales presentation yesterday. I went in hoping for a 1,500 print run and well—I was brilliant! Now I have a very severe problem—how to get all those thousands to actually buy your book. If it comes back after we advance it, I will slit my throat.

![]()

Toni Morrison’s boldness in convincing Random House to print five thousand copies of Barbara Chase-Riboud’s From Memphis & Peking (1974) was a sign of her growing influence as an editor at Random House. While the firm maintained elements of publishing culture that claimed to use literary merit as a core guide for decision-making about which books to publish, Random House was not at all interested in publishing books that caused them to lose money. Even a book that was a critical success and thereby likely to burnish the firm’s reputation needed, at minimum, to earn out. Poetry collections created an especial challenge in this regard. Pitches by editors to acquire a debut collection by an unknown author exasperated sales teams, and yet Morrison prevailed upon her colleagues to trust her instincts that she could sell thousands of copies of a book of poems by a well-known sculptor who was, conversely, completely unknown as a Black woman poet.

The fact that Morrison’s second novel, Sula (1973), was set for wide release in a few days no doubt emboldened her. Based on early reviews of the novel, it would be a critical success, affirming her position as a first-rate writer. Whatever clout she achieved as a novelist could only accrue to her benefit as an editor.

By the time she signed Chase-Riboud up for From Memphis & Peking in 1973, Morrison had learned a lot about the many steps of the publishing process—from acquisition, editing, and design to proofing, pre-promoting, and printing to sales, marketing, and publicity. She had also published books in a range of genres—a literature anthology, a medical handbook, a legal textbook, two collections of essays, a collection of short stories, and a novel. She had not, however, published a book of poetry. This changed quickly when, all in a matter of months, rather serendipitously, Morrison began to work with three Black women poets. In the early months of 1973, she met Chase-Riboud through a mutual friend. By fall, she was in conversation with Lucille Clifton, who was already a Random House author. A few months later, she and June Jordan began to conspire to have Jordan secure a contract with the publisher. At the same time, Morrison was working to recruit other authors and publish other books. What these three women had in common, however, was an editor whose fame as a writer was on the rise and who was willing to use whatever cachet this gathered to publish poetry by Black women at a time when Random House was less than enthusiastic about publishing slim volumes of poetry that were as likely as not to end up on the wrong side of the profit sheet.

The first volume of poetry Morrison published as an editor was Chase-Riboud’s From Memphis & Peking. The volume was also Chase-Riboud’s first book as an author. Like so many relationships in the art world, theirs was a function of having a mutual acquaintance. Lynn Nesbit, who was Morrison’s literary agent at the time, hosted a party in New York where Morrison and Chase-Riboud were both guests. A friend who knew Nesbit and Chase-Riboud incredulously remarked to everyone within earshot—“You’ll never guess what Barbara has done. She’s written a collection of poems.” By then, Chase-Riboud was gaining a reputation as a sculptor of note, but she had no formal training as a writer. She had not even taken a literature class in college. In an act of casual bravado, Chase-Riboud shared some of the poems with Nesbit, who, in turn, invited Morrison to read them. Having a client who was also an editor had its benefits. Morrison liked the poems right away. As she was apt to do for manuscripts she admired, she wasted no time proposing and getting approval to acquire the book. She had a contract drawn up and sent it to Nesbit, who logically became Chase-Riboud’s literary agent. The financial terms were beyond modest—$500 on signing and $500 on delivery of the manuscript. If the firm was going to reluctantly embrace the prospect of successfully publishing an unknown, first-time poet, at least it would minimize its liability by offering a negligible advance.

From Memphis & Peking was published rather quickly by most standards. Morrison and Chase-Riboud finalized the poems and their arrangement in the volume during the summer of 1973 when Chase-Riboud hosted Morrison and her boys for two weeks in France—a bonus trip to their planned vacation in Spain. When she returned to the U.S. with the manuscript in hand, Morrison sent it to the production team and began to focus on publicity for the book. First on the list of promotional work was an event to celebrate the book’s launch. Anxious to collaborate with Random’s publicity associate Caroline Harkleroad on this, Morrison soon encountered resistance from an unlikely source. Chase-Riboud was reluctant to participate in a book party and said so immediately, and she was completely resistant to reading alone at a party. They tossed around ideas about having others read with Chase-Riboud, having her record her readings in advance to play in different rooms if they were able to secure a museum as the venue, or having singer Roberta Flack accompany Chase-Riboud as she read, if Flack was available and willing to do so.

While Morrison had counted on Chase-Riboud’s personality to help sell the book, Chase-Riboud belatedly declared that she wanted the book to sell exclusively on its merits. She desperately wanted to avoid the fate of artists who “tap dance for prizes and coverage.” When she lamented that “even coveted things like the Yale poetry prize has [sic] no meaning because its value is blurred because of its commercial value,” Morrison shot back:

I don’t understand what you are saying about holding a firm line between the work and the publicity. I hope you are right that people who like the work will “do things” for it without being asked—that would relieve us entirely of doing anything at all other than manufacturing it—but it is probably not a good idea for us to take that risk. We have to think of all sorts of anonymous people walking into a book store and wanting to buy the book for some reason—one reason I can give them is that they have heard or read about it…. I must also try to get booksellers to put in [sic] on their shelves and they will do that for one of two reasons: Random [House] says so or they too have heard about it. So. What is that but publicity? … This is a commercial house historically unenchanted with 500 slim volumes of profound poetry that languish in stockrooms.

Morrison had fought hard to get Random House to agree to underwrite a book party, so she was quite frustrated by what she thought was Chase-Riboud’s unwarranted and surprising hesitancy. She went from frustrated to annoyed when Chase-Riboud suggested that Morrison ask two of Chase-Riboud’s friends who were “experts about such things,” as if Morrison and the publicity team at Random House were not. The compromise, in the end, was Nesbit and her husband Richard Gilman would host a party at the couple’s Central Park West apartment on May 23, 1974.

Part of Chase-Riboud’s anxiety, she ultimately admitted, was her husband’s disdain for self-promotion. “Marc…is pathologically against personal publicity,” Chase-Riboud wrote to Morrison. “He thinks one should become ‘famous’ like he did by sitting on a sand dune in the Sahara or in a rice paddy in North Vietnam. So, I’m fighting on two fronts: first my own natural tendency to shy away and his fuss about the whole thing.” Chase-Riboud’s husband, Marc Riboud, was a celebrated French photojournalist best known for photographing ordinary people doing ordinary things. Two of his most famous photographs (one of a workman posed like an angel while painting the Eiffel Tower and another of a woman presenting a flower to armed national guardsmen during an anti-war protest at the Pentagon) were published in Life magazine. Fortunately, Morrison and Chase-Riboud had gotten to know each other well during their two weeks together in France. The rapport they developed helped them withstand the many conflicts that arose as production of the book unfolded. Instead of tension, there was wit. “Your insanity is so interesting,” Morrison wrote, “not at all like most madness.”

To assuage Chase-Riboud’s fears about reading alone (she continued to insist that her voice was too soft, low, and timid), Morrison agreed to read with her.

Be assured that your editor will attend giving you moral support and I am not totally turned off by the idea of reading with you—as a sort of anonymous editor (who admittedly has worked intimately with the work). It would complement—not distract from—the poetry. Also, I do it well. If, however, by that time I am truly famous, as the consequence of my new book’s [Sula’s] publication in January, then you may as well have Ms. Flack…. So. Go ahead and ask Lynn and hope Roberta is free.

She closed the letter with sentimentality and snark: “Love, girl and fuck the sand dunes,” no doubt in response to Marc’s sentiment about publicity and the way he left Chase-Riboud feeling unsure.

The prepublication tussles were not limited to publicity and the book party. They also had ruminating exchanges about the book’s design. In early fall, Morrison sent Chase-Riboud a copy of the preliminary design, noting that they were using Electra for the text type and Weiss Initials for the titles. The copyedit team also had questions about turnover lines, but Morrison agreed to wait until the manuscript was in galleys to address the problem. In response, Chase-Riboud had a list of things she thought needed to be changed.

My feeling is the following: that the designer didn’t read the book and thought: a classy French lady who writes love poetry. Don’t you think so? So, although I really wanted to keep out of it, I first spent seven hours looking at least 3,000 book covers in the three American books [sic] stores in Paris. The poetry covers are the worse. I found two covers I liked: one Fire in the Lake and the other The Savage God…. After about thirty tries (and I did try to work without the framework of the designer’s layout)—(it didn’t work) I have come up with the enclosed layout which I think is superb. I didn’t think I would come up with something I like as much. If you like it, fight for it.

Additionally, Chase-Riboud wanted the fleur-de-lis motif changed, arguing that it was “too complicated and too floral.” She wanted a new type, one that was sexier and stronger, “more American and more mysterious than the original.” The word and needed to be dropped from the title and replaced with an ampersand to highlight the relationship and juxtaposition between the words Peking and Memphis. In her view, very little about the design in draft worked. After all, Chase-Riboud noted, she was a “fallen” graphic designer. So, the Random House designer would understand, she mused.

Morrison’s response was canny. Chase-Riboud had gone to such great lengths to have the cover adjusted according to her design when the copy Morrison sent was for the title page, not the cover at all. Still, Morrison took the opportunity to address Chase-Riboud’s assumption that the designer did not “know” the book.

We talked about every detail of your book. I never worked with a designer who was such a perfectionist.… I think he can switch ornaments—but he chose the one he did from a Chinese silk screen pattern—which he showed me because I thought it was not “Eastern” enough. So much for Sino-French artistic sources…. After I have spoken to the designer (and tell him that you belonged to his guild) I’ll watch for the convulsions, wait for his recovery, then propose the title page change.

In response to Chase-Riboud’s query about how they might handle front matter, the people she wanted to thank especially, Morrison queried:

Will you want a dedication page…as well [as an acknowledgments page]? Sometimes both are included—the latter being a “To Honeypot without whose encouragement this book was certainly done” kind of thing. Your “Thanks to” is unusual at the end—but O.K. if we have a page that does, in fact, announce the end of the book.

Morrison’s artful “To Honeypot” remark was, of course, another dig at Marc, who, in Morrison’s estimation, seemed less than enthusiastic about his wife’s latest adventure. At one point, the tension about Marc’s and their so-called friends’ interventions was so thick that Morrison asked Chase-Riboud if it ever occurred to her that all the people advising her against Morrison’s professional suggestions wanted her book to fail.

When Morrison sent Chase-Riboud the jacket proofs for the book, the passive-aggressive exchanges finally came to a head. Morrison chose a picture of Chase-Riboud holding a piece of her sculpture for the front of the book and another picture of Chase-Riboud for the back. The silver and black color scheme, along with the images, were meant to convey an aesthetic sense of elegance. But Chase-Riboud saw the choice differently. “I find the dust jacket slick and overmerchandised and for no good reason and to the detriment of the poems,” she wrote.

I especially object in the strongest way to Two, repeat Two phtos [sic] back and front. This is unheard of and really too much. The reaction here…is negative in that it becomes another “black book” which is not the case and “look a black girl.” The whole feeling is vaguely sexist, Hollywood racist and exploitive….

To put a fine point on her objection, she also accused Morrison of being trapped in the “mentality of white publishing” and of failing to take advantage of an opportunity to consult with Chase-Riboud to style the book in a way that could have benefited them both. Morrison’s response was measured and matter of fact.

I don’t understand you. Why did you send us 36 pictures if we weren’t supposed to use them—on the jacket or wherever? What did you think we were going to do with them? … Seven calls and two telegrams have been placed to you with no response. But the urgency regarding publicity—not judgment about jacket covers…. No author tells me what to do in that area…. If you wanted an anonymous, plain, uneventful recessive jacket you should never have come to this publisher. The only time that works is when the poet is very well known—as a poet. You are not. The purpose of the jacket is to make people pick it up, fondle it and hopefully open the book. The acid test is on the pages…. Remove it [the jacket] and your book will die in every book store in this country. You have the opportunity to transfer to some people some beauty and sensibility—take a chance.

Morrison did not bother to respond to the insinuation that her imagination had been overtaken by the white publishing world she had learned to maneuver so well. Her commitment to making the publishing industry bend toward her intentions as a Black writer and editor, at least as she saw it, was beyond dispute.

Their evolving disagreement notwithstanding, Morrison continued to try to get attention for the book. She made promotional pushes for it, but it received minimal reviews, even in places like Choice, Library Journal, Kirkus, and Booklist. Poet Albert Aubert found the poems “impressive in their thematic range and complexity.” The Kirkus Review noted that the poems had a “rare combination of strength, grace and ambition” and called the collection “a tough-minded, soft-hearted, often touching and always interesting book.” The most national attention for the book came with a Washington Post article by Angela Terrell, who introduced the reading audience to Chase-Riboud as a poet and world traveler whose poetry was connected to her movement within and across cultures. “Her poems (like) her sculpture,” Terrell wrote, “are a lucid reflection of their creator…a trip from a three-dimensional world to another.”

Limited though they were, all the reviews were favorable. But it did not seem to matter. In the end, the book did not sell well and got too little critical attention from the people and places that mattered. When Chase-Riboud made the appeal for a second push of publicity, as though she had cooperated with the first one, Morrison would not entertain it. Instead, she noted that advertising and promotion money, perhaps counterintuitively, was reserved for books where sales were encouraging. “Had my own better judgment been executed,” she confessed, “we would have printed less the first time around. The obstacles I anticipated in sales…proved to be too strong.”

Morrison was proud of From Memphis & Peking but disappointed that avoidable missteps kept a well-done book out of readers’ hands. While she had no problem remaining friends with Chase-Riboud, Morrison had run out of patience when it came to the editor-author relationship. So when Chase-Riboud pitched to Morrison an idea about an epic poem on Sally Hemings, Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved Black mistress, Morrison quickly declined the project but not before warning Chase-Riboud that neither the epic poem nor the diary format, both of which Chase-Riboud was considering, was the right genre for a book about such a complex woman. Years later, it was former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis at Viking, not Morrison at Random House, who would bring Chase-Riboud’s Sally Hemings: A Novel (1979) to life. To everyone’s delight, Sally Hemings, unlike From Memphis & Peking, sold well and received the 1979 Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize for best fiction by an American woman.

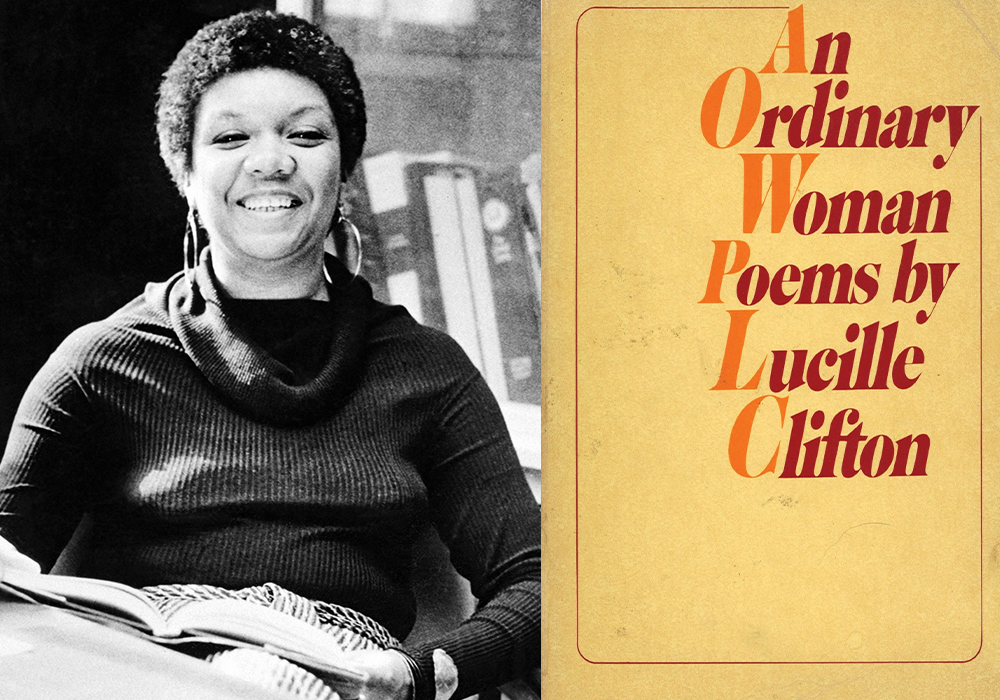

![]()

The same year From Memphis & Peking was released, Morrison published Lucille Clifton’s An Ordinary Woman. Random House had previously published Clifton’s Good Times and Good News About the Earth, and both books had done well. While Morrison had been in touch with Clifton before (to provide promotional commentary for Toni Cade Bambara’s Gorilla, My Love), Natalie Lehmann-Haupt, Alice Mayhew, and Nan Talese had been Clifton’s editors for the first two collections. When Mayhew left the firm in 1971 and moved to Simon and Schuster, Talese took over as Clifton’s editor. Then, when Talese left, Morrison became Clifton’s editor. Morrison admired Clifton’s poetry, so their working together seemed like a logical and natural fit. The two had known each other briefly as students at Howard University, too, with Morrison graduating the year Clifton arrived. They had enough people and places in common that their editor-author relationship became cordial much faster than it might otherwise. Clifton’s reputation and experience as a well-regarded published poet and her levelheadedness offered a welcome change from Morrison’s work with Chase-Riboud.

In fall 1973, Morrison and Clifton met in New York to get acquainted and to talk through Clifton’s ideas about the project she wanted to work on next. Following their meeting, Morrison wrote to Clifton to express excitement about the work Clifton’s agent, Marilyn Harlow of the Curtis Brown Agency, had recently sent.

I have read all of the new poems Marilyn sent, and they are so good—very different (the feel of the collection) from the other two…. It’s not just content—it’s the what? Fabric, I guess, or tone. Mellow. Less of the acid in Good Times or the outrage in Earth. Mind you, you cover that acid in comfort—but it was there anyway.

For Morrison, the exploration of the ordinariness of Black women, individually and as a group, was a venture into the extraordinary. The need for acid and outrage was indisputable, yes; but universalizing Black women’s discrete experiences was uniquely appealing and necessary.

Clifton was ambivalent about what to call the collection. Morrison’s first recommendation was “In My Own Season,” because the book finished with what she described as a very strong coming-of-age thread. She also offered phrases from poems in the collection as alternatives, “The Woman Jar” or “Thawed Places.” In the end, they decided on An Ordinary Woman, lines taken from the collection’s final poem.

With few exceptions, Morrison’s editing of the poems in the volume was light. Clifton had titled a poem “I Am a Black Woman,” for instance. “There must be 800 of these,” meaning poems with that title, Morrison wrote. So, she suggested calling it “And I Am Not Done Yet,” which was the first line of the poem in draft. In its published version, Clifton shifted the first line to the title, dropped the conjunction “and,” and began the poem with the line “as possible as yeast / as imminent as bread.” The poem “To Ms. Ann,” Morrison noted, worked “marvelously.”

But please delete the fourth verse. You don’t need it—the three other images are thunderous and should not lead up to “Little Rock spit.” … The other verbs are watched/walked/handed—very civilized, very poisonous. Spit—well—no.

Clifton did publish the poem with a fourth stanza but without the vitriol of the original one. In the poem, Ms. Ann is a stand-in for white women who, through the years, have taken full advantage of their mismatched relationship with Black women.

For Morrison, and Clifton evidently agreed, the first three stanzas did the work of being righteously dismissive, poisonous in fact, without reducing the poem’s speaker to the incivility of white women who spat at children in Little Rock. “Little Rock pulls the poem out of the ages into the newspapers,” Morrison argued. The new stanza, in contrast, added the final blow, making clear that the reality of a shared humanity remained unacknowledged by the least humane ones.

The difference between Clifton’s success and Chase-Riboud’s, in terms of their both being Black women who published slim volumes of poetry in 1974, can be explained in at least two ways. Clifton was an established poet, for one thing. The other related benefit she had was an established Black reading audience. Accordingly, she did not need white women’s book clubs to sell books, which also meant she could be critical of the ways white women upheld racism without fear of being shut out.

After publishing three books of poetry at Random House, Clifton finally completed the book of prose she had begun years earlier, Generations: A Memoir (1976). She had signed a contract for the book in April 1969, and she and Morrison talked about it when they first met. But they decided to publish An Ordinary Woman first in large part because Clifton did not feel ready to publish the memoir. She had tried to explain the concept of the book to her then-editor, Alice Mayhew. “It will take…months,” she had confessed,

because the bringing of one’s insides out, especially for somebody who has made a life of holding very carefully her insides, is some hard. Also I think that after I bring them I shall trot them back in to hold again. That’s hard…. I shall take me apart and then put me back together; but you know, I can do that…if I just would.

It took five years and a new editor for Clifton to accept her own challenge. She appreciated having Morrison, another Black woman, as a sounding board for Generations. Morrison’s enthusiasm for the book was immediate. Subsequently, they talked at length by phone about it. A few days after their conversation, Morrison wrote: “Generations is so good. I do love it. What a good time I’m going to have publishing it.” With Morrison on board as the editor, Clifton dedicated herself to finishing the book finally. The narrative was still sketchy in places, Morrison told her…but, by and large, Morrison assured Clifton that the core of a fascinating story was there. The matter of writing the book was also complicated by the backlash Clifton experienced at the hands of her family after publishing an essay, “The Magic Mama,” in Redbook in November 1969. Her brother and her relatives were upset by it, and this blocked her ability to write more about her family without feeling guilty. But with all six of her children in school finally, she committed to focusing her attention on completing the book.

Reviews of the book were plentiful and mainly positive. The sixty-nine copies Morrison sent to Random House’s regular press list and the twenty copies she sent to the poetry and “Black interest” list yielded some fruit. The book scored a short mention in the New Yorker, which had a unique readership. And Morrison was hopeful that Reynolds Price’s long review in the New York Times Book Review would be helpful to sales. Unfortunately, it was not. Generations went out of print eight months after publication. At one point, Morrison lamented to the sales team that Clifton was making appearances at locations where the book was not available. Finding the source of disconnect was a challenging one. Was the bookseller ordering enough copies of the book or not any at all? Were the people coming to hear her read reliable purchasers? It made no sense for a bookstore or event space to invite a writer without having the writer’s books available for purchase. Such neglect, Morrison argued, was enough to outrage an established author, which Clifton was by then. Clifton had already begun to publish books with Holt, Rinehart and Winston, and with Dutton. Morrison suspected that Clifton submitted Generations to Random House only because it had been contracted years earlier with the lure of a paltry advance. Morrison’s fear that Clifton would move to another publisher for good came to fruition, and, to both women’s dismay, they never worked together again. Clifton went on to be one of the most beloved contemporary African American poets, and Morrison, though not as her editor, continued to be one of her greatest admirers.

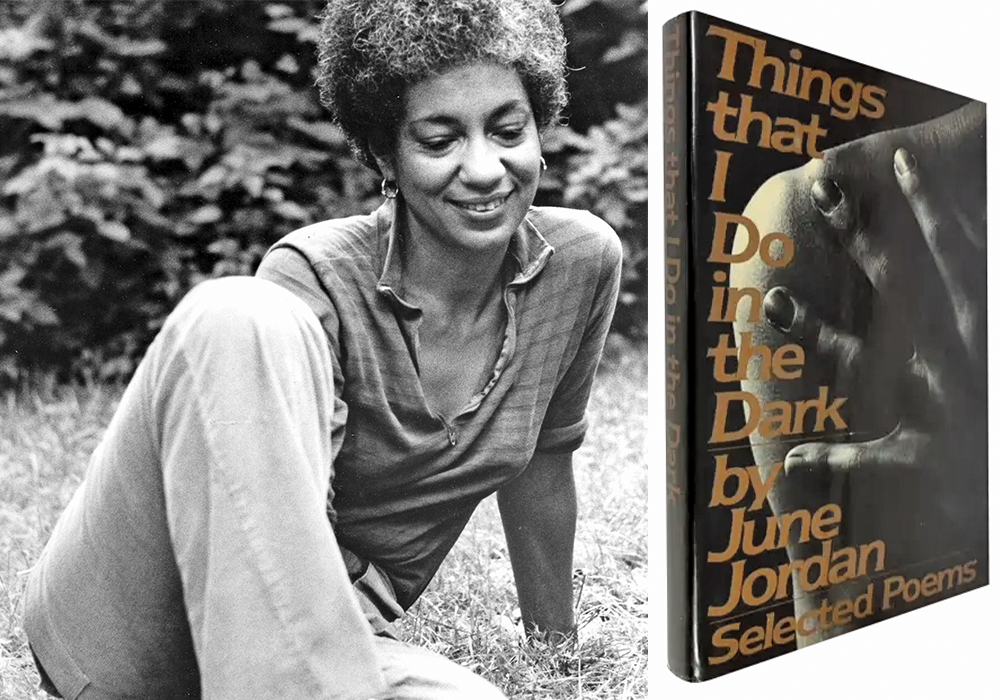

![]()

Either by design or coincidentally, Morrison and June Jordan began discussing publication of a collection of Jordan’s poems a few months after Morrison brought out Chase-Riboud’s From Memphis & Peking and Clifton’s An Ordinary Woman. Jordan had already published several books and was, by all accounts, a popular poet who did the hard work of promoting her writing to the full range of audiences. She was well connected in Black poetry circles and supported by the best-known critics. She commanded standing-room-only crowds at most of her readings, while also managing to publish in poetry magazines and journals—a nexus that highlighted her versatility. Morrison was enthusiastic about working with Jordan and committed to fighting to get Random House to publish her work. If she had any chance at publishing poetry she admired and that could have commercial success, Morrison was convinced it would be with Jordan.

“I want very much to publish a book of poetry by June Jordan,” Morrison wrote to Jim Silberman [editor in chief at Random House] in June 1975. “Aside from the quality of her work, the attached sales information should remove the obvious reluctance I would have about taking poetry on.” Silberman appreciated Morrison’s advocacy and supported offering Jordan a contract, in principle. But the only way the firm could take her on, he told Morrison, was if Random House became her only publisher. Because Jordan was under contract for a novel at Simon and Schuster, the initial contract negotiations were stalled. And Morrison and Jordan’s new and untested relationship began to fray before it could even unfurl.

What began as an exchange between writers with mutual respect devolved rather quickly into a series of miscommunications. Initially, Morrison suggested to Jordan that she could get a contract rather quickly, in a matter of days. Weeks went by, however, with no word from Morrison. What Jordan did not know was that Morrison needed to find a way to respond to Silberman’s concerns about how well Jordan could perform as a novelist. There was, still, the matter of the Simon and Schuster contract; and Silberman was scheduled for a monthlong vacation. Hearing nothing and having grown impatient, Jordan had her attorney reach out to Morrison, first, for an update and, subsequently, to return the manuscript. Morrison returned the manuscript as requested but also took a moment to write to Jordan directly.

Dear June:

Last Thursday I returned your material to your lawyer at her request. I didn’t want to call you with if-y information—only with a yes or no…. I can’t figure out why you didn’t trust me; I know you wanted things settled but, had no idea there was a time crisis involved…. I would have felt so much better if you had given me the deadline and the ultimatum yourself. Keep doing the work though. I love it.

Jordan’s response was immediate. It was also alternately complimentary and incredulous. She led with admiration.

Of all the people remotely able to publish my poems, you are the one I have been hoping to interest, and work with; I would hope that you know this is because you are the beautiful writer who has given all of us the works you have created…. In addition, what you have done, as editor, for Black letters, per se, seems to me altogether wonderful, and essential.

She then pointed out that after their meeting in May (and a phone call the next day), Morrison suggested that the contract would come quickly. “Well, during the interim five or six weeks that have passed since that call,” Jordan wrote, “I heard nothing from you—no phone call, note, letter, contract: nothing at all. The unexpected silence was most uncomfortably reminiscent of the silence my previous publisher interposed between us.” She read Morrison’s silence as disinterest in the project, even if that disinterest was confounding. So, she directed her attorney to inquire on her behalf—not so much because she wanted to apply pressure but because she had been out of town, and her attorney was based in New York City. She ended the letter on an apologetic and hopeful note: “I am sorry that because we don’t know each other well enough to accurately assess the import of an exchange or, on the other hand, of unexpected silence, things have come to their current resolution that I am seeking, with this letter, to obviate, and move beyond, positively.”

Perhaps to eliminate confusion and to make her point explicitly, Morrison laid out the facts as she saw them over four pages. Her first point was that she, not Random House, was interested in publishing Jordan’s poetry. In other words, no executive had prodded Morrison to sign Jordan up for a book. Rather, Morrison had sought her out personally and would have to convince the firm to offer Jordan a contract. That reality was attended by major challenges—the difficulty of placing poetry, the difference between selling juvenile / young adult books (which Jordan had done with some success) and adult trade books, and the publisher’s near exclusive interest these days in making a profit.

Morrison also took the opportunity to answer specific questions Jordan had posed about the contract. There would be no guarantees of promotion or of a publication date. And Random House was indeed interested in a multibook contract—a book of poems, an adult book on Bessie Smith, and Jordan’s novel, for which the publisher would have to pay Simon and Schuster since Jordan had received an advance for the book. “A strict profit-making sequence would be 1st Bessie, 2nd novel, & 3rd poetry,” Morrison wrote. “Your preference is just the reverse—and I can accommodate you, although it would be harder, since you are the determiner of the way you work. And I wouldn’t meddle with that.” The back-and-forth about the contract continued until they finally reached an agreement but not without first battling each other rhetorically in letters, signifying along the way.

Morrison claimed that her four-page letter was an attempt to be clear. Jordan took offense to its forthrightness. Morrison, for instance, was blunt in saying “Random House (the people whom I must persuade to issue a contract) are not at all interested in publishing your poetry. I am.” Even if Morrison wanted to make the point that it was her advocacy alone that would make a contract possible, she did so by highlighting the publisher’s complete disinterest in publishing Jordan’s poetry. The tone of the letter also took Jordan aback. Jordan was confident in her ability to sell books and quite proud of her track record in doing so. But Morrison reminded Jordan that her best success in selling books was limited mainly to juvenile books, which relied on institutional sales to libraries and schools and largely as paperbacks. Adult trade, conversely, made its money in sales of hardbacks in bookstores, mass paperback reprint sales, and first serial rights. And there were no first serial rights in poetry.

Jordan claimed to be so shocked by Morrison’s letter that she had to read it repeatedly with time between readings to be sure she understood what Morrison had “elected” to write. Morrison wrote back that Jordan’s letter “befuddled” her, so when she received it, she tried to call Jordan repeatedly. But she kept getting a busy signal. So, she wrote the letter and opted to dispense with “the normal language of [the] industry (euphemisms)” and to write, instead, the way she talked. She thought Jordan’s precise questions deserved very precise responses. After noting that the duo had now had two huge misunderstandings, Morrison closed the letter with a bit of sarcasm and a quip. Since something must be wrong with the way she communicates when she does so forthrightly, her recourse must be to communicate “in the sly manner that most people use when they talk or write about business.” And that was a pity, she wrote. Then, in the final line of the letter, she inquired about how Jordan was feeling: “How’s your neck? Are you still taking the medicine?” Jordan wrote back that she was better but still confined and did a wellness check of her own—“How are you? Less harried, I hope?”

After months of back-and-forth, the contract for a book of poems and a book on Bessie Smith was finally executed and signed in May 1976, and Morrison and Jordan began the work of selecting the poems, giving them titles, and arranging their order in preparation for publication. Jordan had published three collections—Who Look at Me (1969), Some Changes (1971), and New Days: Poems of Exile and Return (1974)—and contributed her poems to edited collections. So, they had plenty of poems from which to choose. Jordan warned Morrison, however, that she did not yet own the copyright for the poems in Some Changes, so her preference was to focus mainly on the poems in New Days and to use poems from Who Look at Me if needed. This was in addition to twenty new poems she completed for the new collection. Jordan’s biggest concern was making sure her growth as a poet was foregrounded in the arrangement rather than choosing poems that suggested a coherent vision. She wrote to Morrison:

When you begin with Who Look at Me, and you work through all the poems…you do see that there have been serious changes of rhythm, emphasis, structure, purpose, and concern….

If you look at the love poetry of Some Changes you will have to conclude that, by the time there were New Days, I had been rescued from some rather serious albeit contemporary problems of fear, self-doubt, and trembling uncertainty. In New Days, the love poetry is alternately casual, sexual, mocking, kidding around, direct, and so forth, as well as serious….

Jordan was also concerned about the similarities readers might observe between her work and Ntozake Shange’s. “Shange’s poetry derives much from her study of my work,” Jordan noted; “this is clear if you know my work…but if you don’t know when and who, it’s the kind of problem I would really rather not have to cope with, at this point in my life.” Dating the poems individually was one way to address all the concerns.

Morrison was concerned that a thematic organization might do some poems a disservice. With a series of love poems in sequence, for instance, the power of one poem or another could too easily be deflected simply because of where it falls in the grouping. Organizing this collection according to the books the poems were published in would likely cause copyright problems, since that would essentially be a reprint of each collection. A combination of theme, tone, and chronology seemed to be one way to solve the problem. And while it was not a perfect solution, it did at least create a strong editorial position on which they could build. The key would be to select only the finest poems for inclusion. Morrison left the task of choosing which poems were among the best to Jordan, at least for the first pass. “My own ideas lean toward the successful poems which are not always the ‘important’ ones,” Morrison wrote. “So I’d like your list first…. Once I have your list, we can argue.” There were minor glitches, too, that would need to be addressed. The beginning lines of two poems were identical, so one would need to be changed. Another poem had two copyright dates, so the correct one needed to be determined. Two poems had titles that were too closely related and would need to be differentiated somehow. And a poem with one title had a page and a half of the same lines from a poem with a different title. This would need to be corrected.

Having overcome the rocky start, Jordan and Morrison managed to publish Things That I Do in the Dark with only minor difficulties in the end. But the friendship that could have been never was, despite their attempts to support each other outside of their editor-author relationship.

Despite her best efforts to work with Black women authors to publish commercially viable volumes of poetry, Morrison’s work with Chase-Riboud, Clifton, and Jordan did more to convince the determined editor that the firm’s reluctance to publish poetry was well-founded than it did to convince her that she could beat the odds.

From the book Toni at Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship. Copyright © 2025 by Dana A. Williams. Reprinted by permission of Amistad, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Dana A. Williams is a professor of African American literature and the dean of the Graduate School at Howard University. She is the former president of the College Language Association and the Modern Language Association and the author of In the Light of Likeness—Transformed: The Literary Art of Leon Forrest (Ohio State University Press, 2005).

Chase-Riboud: Susan Wood via Getty Images; Clifton: Jackson State University via Getty Images; Jordan: Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute