In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 124.

Let’s face the facts: Setting is undercelebrated compared to its flashier craft cousins. This is especially true when it comes to discussing narrative engines. While we talk about character-driven fiction, concept-driven fiction, and even voice-driven fiction, rarely do we discuss setting-driven fiction. Setting is often an afterthought. A touch of color. A splash of imagery as toothless as a stage set—or worse: intangible as air.

When setting does receive attention in discussions of narrative momentum, typically it is within the framework of “man versus nature”—one of several traditional sources of conflict in literature. A person is pitted against forces of the wilderness: a grizzly bear, an icy river, a very tall mountain. The person must fight or succumb. The possibility of death looms, and this generates conflict, choices, consequences—which drives plot. Canonical examples include Herman Melville’s Moby Dick and Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea.

Cool…but isn’t this construct a bit antiquated and limiting? Perhaps even an expression of the subjugation-minded colonial heteropatriarchy? Of an outsized fear of the wild? Other settings can provoke just as much conflict and danger in our everyday lives. Characters need not wander mountain forests to be antagonized by their surroundings. A Panera Bread, or a maternity ward, or a corner office in a high-rise skyscraper can impose challenges, which in turn can generate conflicts, choices, and consequences for our fictional characters.

But here’s the other thing: What if setting need not be antagonistic to be narratively propulsive? What if we expanded beyond “versus” to include other kinds of relationships to a setting—relationships that perhaps involve care and maintenance, or even affection?

An example of such a relationship can be seen in Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman. In this novel, the protagonist, Keiko Furukura, works at the Hiiromachi Station Smile Mart. She is diligently—even religiously—committed to caring for and maintaining the store’s atmosphere of consistency. Here’s an except (translated from the Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori):

As I arrange the display of newly delivered rice balls, my body picks up information from the multitude of sounds around the store. At this time of day, rice balls, sandwiches, and salads are what sell best. Another part-timer, Sugawara, is over at the other side of the store checking off items with a handheld scanner. I continue laying out the pristine, machine-made food neatly on the shelves of the cold display: in the middle I place two rows of the new flavor, spicy cod roe with cream cheese, alongside two rows of the store’s best-selling flavor, tuna mayonnaise, and then I line the less popular dry bonito shavings in soy sauce flavor next to those. Speed is of the essence, and I barely use my head as the rules ingrained in me issue instructions directly to my body.

At this Smile Mart, the drinks and snacks never run out because Keiko replaces them. She is reacting to her setting—forever in flux due to consumer purchases and the passage of time—and her choices have consequences, especially as her commitment to the store pushes her further from cultural norms around age and gender. This creates conflict.

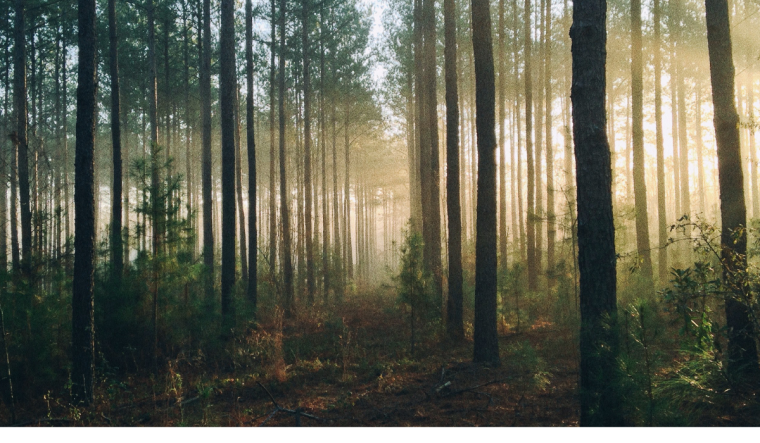

Care for a setting—be it for a convenience store or a grove of saguaro cacti—can generate conflict, as much as a battle with these places. This seems significant for fiction writers looking to create dynamic, complex narratives. It also seems significant for those interested in changing our relationship to our environments, natural and otherwise. If a tree falls in the forest, maybe we won’t hear it—we assume setting has no impact upon us. Or we do hear the tree and we run out of its way, screaming—antagonized. Or maybe, just maybe, we hurry toward the tree to see if we can help. Maybe we find a bird nest knocked to the ground—a nest we choose to place carefully, consequentially, in the branches of a yet upright tree.

Allegra Hyde’s first novel, Eleutheria, is forthcoming from Vintage on March 8. Her debut short story collection, Of This New World, won the John Simmons Short Fiction Award through the Iowa Short Fiction Award Series. Her writing has also appeared in numerous publications, including American Short Fiction, Kenyon Review, and Tin House. Born in New Hampshire, she lives in Ohio and teaches at Oberlin College.

Art: Steven Kamenar