During the summer of 2022 I attended the Postgraduate Writers’ Conference at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, where I had the good fortune of taking a memoir class with Ira Sukrungruang, the author of six books, including the memoir This Jade World (University of Nebraska Press, 2021). At one point during our residency, Sukrung-ruang outlined the risks of working on a single draft over the years, how a memoir can lose its fresh point of view, and how overworking a draft could make it less cohesive. His recommendation was to complete our drafts in concentrated bursts of time, about three to six months.

I nodded, though I strongly doubted it could ever be possible.

My memoir had been simmering for the past six years. While working full time, I had finished two manuscript drafts that required radical restructuring, new outlines, and new chapters. Thanks to fantastic critique partners, I was becoming a better prose writer with each draft. But timing was an awkward subject. Especially at parties.

“Has an agent seen it yet?”

“How long do people typically work on memoirs?”

“If you have a full draft, why not just self-publish it now?”

And my least favorite: “Writing a memoir must be good therapy. It probably doesn’t matter whether you finish it or not.”

After the residency I threw myself into my writing. I had quit my full-time job as a public school teacher and was working freelance, so I had more time than ever to write, but after a few months I was again adrift with no end in sight. When I was focused on poetry, I got by with writing intuitively until I was finished. This approach clearly did not translate to prose. I needed to see my work through a bigger framework, but I had no idea where I could find it.

That’s when data modeling came into my life.

![]()

That fall after the residency I learned the skills necessary to work as a freelance digital copywriter. I drank from a fire hose of new ideas and regularly found myself in unfamiliar contexts. At a networking event someone told me about a workshop on information architecture called Modeling for Clarity, hosted by an organization called the Understanding Group. Based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, the organization is devoted to helping people clarify and make sense of complexity through data modeling. The copy on its website explains how since 2011, the group’s consultants have been making the complex clear in digital spaces. Though I was presumably focusing on getting professional work skills when I signed up for this four-week class, I couldn’t help but think about the possibility of perhaps bringing clarity to my manuscript as well.

My instructors, Joe and Travis, were information architects and designers. Information architects organize digital information so that users can easily find their way when navigating web pages. They categorize and rearrange abstract information, visualizing (modeling) relationships between data points to make these relationships as clear as possible.

In our first class, Joe told us that we already modeled information every day without even knowing it. We all use mental models to make decisions, like categorizing guests’ dietary restrictions for a party, putting together a training schedule for an upcoming half marathon, or deciding where to put a sofa in a crowded living room.

When relationships between things get complex and we’re confused, creating a visual model to make our thinking explicit can come in handy. Here’s an example I have personally experienced: Let’s say you buy a home and need to renovate it. How can you understand the relationship between the cost of hiring out all the work versus the time it will take to manage the project and do the work yourself? What if it’s not clear how much effort some projects might require? And how can you factor in the emotional toll of doing the work yourself?

Wrestling with this kind of complexity was the focus of the class. By making the relationships between data explicit, we could find clarity. And by bringing clarity to complexity, we could more easily discover next steps for just about any project.

For our first real assignment we were asked to model some part of our life or work where we wanted the kind of help that models could offer. My mind jumped to the place in my life that was most muddled and important.

“Can I model a time line for finishing my book?” I asked the instructors during office hours. “Or do you want me to do something more techy?”

“Go for it,” said Joe. “It might take a while because there are quite a few aspects—things to pay attention to—and you might need more than one model. But you can model anything.”

I told them about the frustrations surrounding my book. How every time I revised a chapter, surrounding chapters needed repair. How time itself was beginning to seem like a meaningless concept in relation to a book. How after working on this project for six years, I could no longer see the finish line.

“Well,” said Joe, “you’ve done the first step, which is deciding on an intent for your model—or models. Your next step is figuring out the current state of your project.”

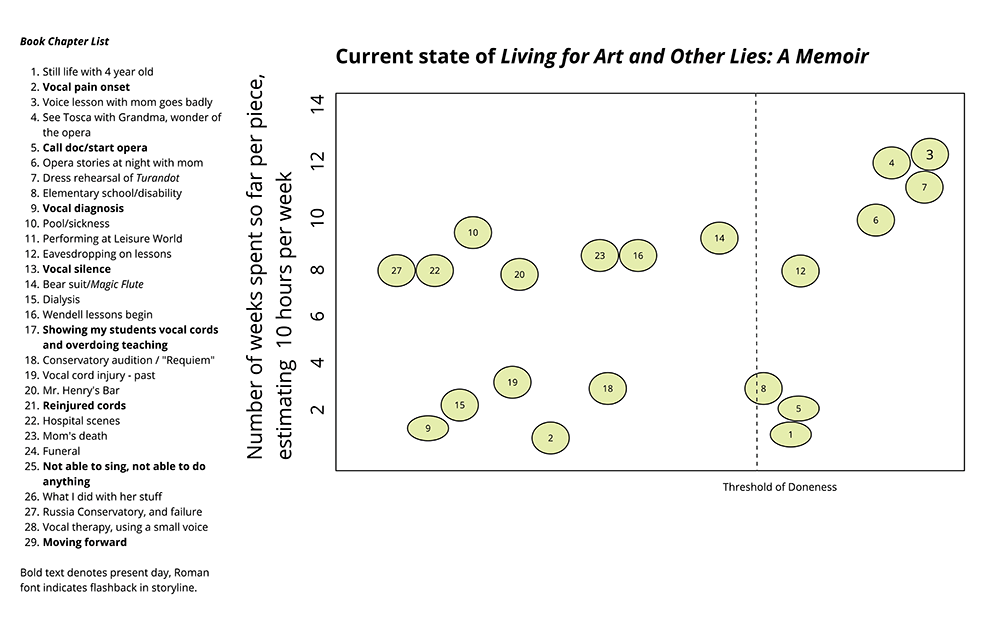

Joe asked me what aspects of my draft were important to the project’s success. These aspects were pieces of data I would make explicit in my models. I chose three: (1) chapters of the manuscript, (2) time spent on each chapter, and (3) the “doneness” of each chapter.

I had defined the intent of my first model—to visualize the relationship between time and my writing process up to now—and I had defined the aspects I would visualize. Now I was ready to sit down and make the abstract tangible. To make my model I used a whiteboarding software called Miro.

I decided to number each of the chapters of my manuscript, because numbers were easier to plot on a chart than titles. Since I was doing a radical revision and hadn’t even outlined some chapters, I held my nose as I guessed at nascent chapters, giving them vague names like “Moving forward.” My perfectionism revolted inside me, but I kept going, because this was my homework, and I was beginning to believe that a model could in fact help me.

On the y-axis, I plotted out the number of weeks I’d spent on each chapter, with the assumption that I wrote ten hours each week. Again, I had to take wild swings to guess at these numbers and keep telling myself not to let perfect be the enemy of good.

On the x-axis, I plotted the “doneness” of each chapter. How ready was I to share the chapter in its current state? I decided to create a dotted line to mark items that felt “done enough” and items I still wanted to rework. For lack of a technical term, I called this the Threshold of Doneness.

I hadn’t made a chart like this since high school, and I was thrilled with the result.

After the pride wore off, I examined my model more closely. I was shocked by the eighty-plus hours I had spent on some chapters. Was this normal? What was normal? Had this whole writing thing been a complete waste of time? But then I reflected on how writing those chapters taught me essential prose skills and ways into my subject matter. Without those hours I wouldn’t know how to write indirect dialogue or understand how to play with time in memoir. Because of these learning chapters, my current writing process was more efficient and successful.

At office hours I talked excitedly through my model with Joe and Travis. We discussed the large variations in time spent on pieces and how the chapters I was writing now, for the most part, took much less time than the ones before. Joe and Travis affirmed what I was saying, that not all chapters should be thought of the same. The chapters I wrote first were a different part of the process. The chapters I was currently writing were taking under twenty hours each, which would be a good time estimate for creating new chapter drafts.

I had modeled the current state. Now for the real trick: modeling the future.

![]()

I returned to office hours the next week. I had clarity about what I’d done so far, but how would that help me model a time line for finishing this draft? Also, there was another layer of complexity I wanted to add to my model: Because I was freelancing, my work hours could be more flexible. Could I model the impact of more or fewer hours of writing?

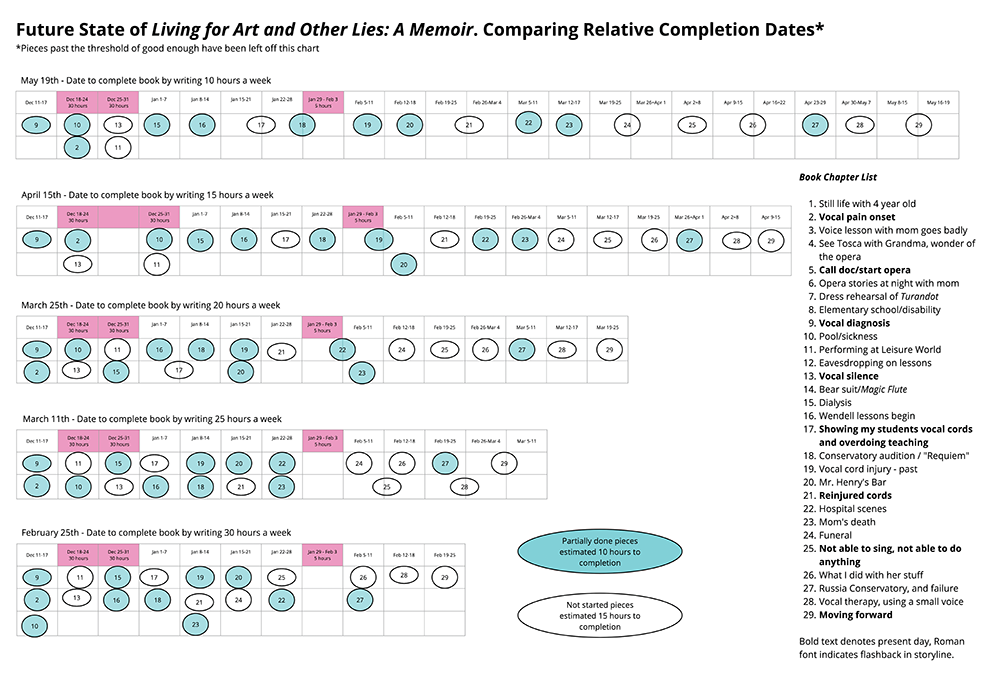

Joe and Travis responded with an enthusiastic yes. These models were meant to account for complexity, after all. Travis offered me a three-step process. First, estimate the time needed to finish each chapter. Second, figure out my time limitations. And, finally, create charts plugging in the number of pieces left to finish using different numbers of hours per week.

The look on my face must have betrayed my confusion.

Travis held up his hands and told me to take a deep breath. “Don’t worry, you can do this,” he said. “You already have everything you need.”

He explained the process again, one step at a time. I took notes.

Step 1: Create an estimate of the time needed to write a chapter.

On my current-state model, I had outlined three different kinds of chapters: (1) chapters that were good enough, (2) chapters that needed work, and (3) chapters not yet written.

To create an estimate of how long it would take me to write new pieces, I averaged the time spent on recently written chapters using my first model. I calculated between fifteen and twenty hours per chapter. For chapters I had begun but that still needed revision, I halved the estimate to come up with ten hours.

Joe and Travis wisely recommended tripling my estimate of hours to complete each chapter, which was great advice that I respectfully declined to implement.

Step 2: Figure out the limitation and variability on hours per week.

While taking this class I was also freelancing, substitute teaching, and learning a new career. I had flexibility in my weekly hours to work more or less. I also had periods when my timing was more rigid, such as weeks when I was subbing full time, and periods when I knew I’d want to write more, such as winter break.

I created a table that displayed my limitations and flexibility for the next six months. I was one step closer to my model.

Step 3: Create time lines to reflect different levels of work time or commitment.

When Travis started explaining this third step, my body buzzed. I was beginning to understand the power of modeling. I was no longer just a writer; I was an information architect who could make abstract data visual.

How many hours could I actually write per week? I made different models using weekly rates of ten, fifteen, twenty, twenty-five, and thirty hours. Though creative writing for six hours a day, five days a week seemed unsustainable and unwise, I wanted to model it and see the impact it would have on the manuscript’s completion date.

Having gotten my marching orders, I thanked my instructors and logged out. I got myself a cup of coffee and started to make my future-state model.

As I sipped, my inner critic began to do her thing—your model isn’t exact, you’ll never finish, what will happen to your model when you get writer’s block—and I firmly asked her to stop. I was too far along this road to let doubt paralyze me. And, besides, this model was a draft. It was there to give me direction, not to control me. This model would allow me to base future decisions on data, not just whimsy or fear.

An hour later I finished my future-state model, which was simply a complicated calendar showing possibilities for the next six months.

On this future-state model, the top row shows the manuscript completed at the steady rate of ten hours per week, save for the weeks marked in pink on each chart, which reflect the weeks when I had time limitations or extended amounts of time to work. The bottom row shows what happens if I’m writing thirty hours a week. I color-coded chapters to separate unwritten chapters from chapters that needed revision, since each type required different amounts of time.

Writing for ten hours a week, I’d finish on May 19; writing for thirty hours, I’d finish on February 25.

Working with either date gave me an hours-per-week goal—something measurable, concrete, and doable.

![]()

After making these models, I felt like a wizard. Having this information was so different from feeling embarrassed when asked about writing time lines. I had clear dates that I could talk about. And even though they were imprecise, actual dates offered me actual goals.

It chilled me to think of the May 19 finish line, which at the time seemed so far away. But keeping the momentum to write thirty hours per week and finish before March seemed like a road to burnout, the worst possible outcome since it would lead to my abandoning the project for months.

The most reasonable time lines involved about fifteen hours per week, writing about three hours each weekday. I could do that. And if I stuck to this schedule, finishing this draft in mid-April would be reasonable. If I finished later, that would be okay too. And if I needed to model again, based on new information, I could do it myself.

As Joe told our class repeatedly during Zoom calls, there is no single right way to model information. It’s not about making something beautiful. It’s not about precision. It doesn’t matter what tools you use, whether graph paper, a journal, a spreadsheet, or drawing software. (I used digital software mostly because I hate using rulers.) The modeling process is about two things: first, getting clarity on what you’re trying to figure out to reach your desired outcome and, second, using your model to move forward with assuredness and self-accountability.

Your model will tell you at a glance if you’re showing up at the desk like you said you would.

Your model won’t lie about exactly where you are in the time line of your big project.

As I write this, not everything is going according to my plan. Freelance work picked up. In December I developed a sinus infection and got little done. There were three weeks in February when I didn’t write. The braided structure of my memoir is no longer intact, so some pieces are being removed from the manuscript. I wish I had followed the advice of Joe and Travis and inflated the estimate for how long everything would take. But hindsight is twenty-twenty.

Does that mean something’s wrong? Am I failing? Do I feel like less of a wizard?

Absolutely not. Because I modeled the process of finishing the book and kept all the charts I made, I can adjust them. In fact I’ve already adjusted my time lines and am planning for a draft completion date around the time you’re reading this.

I’ve got this. And with the tools of modeling, you do too.

Judith Wilding is working on “Living for Art and Other Lies,” a memoir about an opera singer’s daughter who, grief-stricken after her mother’s death, leaves college for a Russian acting school, then embarks on solitary travels in Eastern Europe where, thanks to the care of fellow travelers, she discovers the possibility of a less grand but more grounded life.

Thumbnail credit: Ilana Cloud