It used to be that when a writer bestowed human qualities on an animal—the ability to speak, for instance—it almost always meant trouble. George Orwell's menacing midcentury classic Animal Farm (Secker & Warburg, 1945), a satire on the development of the Russian Revolution, certainly set the tone for the four-legged fiction that soon followed. The terrifying fable begins with Old Major calling the barn animals together to tell them of his pig dream: "Now, comrades, what is the nature of this life of ours? Let us face it: our lives are miserable, laborious, and short…no animal escapes the cruel knife in the end."

Major is right about the life of the farm animal, but his real message (and Orwell's) is grander and darker—and reaches far beyond the animal kingdom: "Man is the only creature that consumes without producing," he continues. "He does not give milk, he does not lay eggs, he is too weak to pull the plough, he cannot run fast enough to catch rabbits. Yet he is lord of all the animals." What the animals mean to do, of course, is set things right. But soon enough, they mess everything up.

Other walking, talking literary beasts that followed in Major's dark shadow include the canine in Mikhail Bulgakov's Heart of a Dog (Harvill Press, 1968), who gains human intelligence after a Moscow professor transplants human glands into the unfortunate canine's body, and the German cats in Art Spiegelman's graphic novel Maus: A Survivor's Tale, which won a Pulitzer Prize Special Award in 1992.

Today, animal lit is broader in scope and occasionally even benevolent in nature. This variety is evident in the genre's more recent successes—among them, Paul Auster's austere dog tale, Timbuktu (Henry Holt, 1999), Sigrid Nunez's "mock biography" of Virginia Woolf's pet marmoset, Mitz: The Marmoset of Bloomsbury (HarperFlamingo, 1998), and Susan Fromberg Schaeffer's warm enchantment, The Autobiography of Foudini M. Cat (Knopf, 1997).

Already this year, two wildly different novels featuring animal protagonists—one with dark Orwellian whiskers, the other with a softer, more fragile underbelly—join the menagerie: Verlyn Klinkenborg's Timothy; or, Notes of an Abject Reptile, published in February by Knopf, and Sam Savage's provocative debut novel Firmin: Adventures of a Metropolitan Lowlife, forthcoming next month from Coffee House Press.

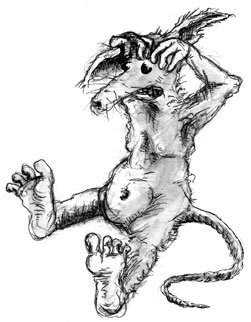

A direct descendent of Orwell's Animal Farm, Savage's Firmin begins as a lovely and harmless tale of a wayward rodent lost in Boston. At first, the incidents of plotted terror are manageable—a struggling mother with thirteen babies but only twelve teats, the endless hunt for food, the keeping safe and warm—but later in the novel, Firmin falls upon a dark fascination in the form of a human named Norman Shine, the owner of a hole-in-the-wall bookstore, Pembroke Books. Firmin takes to feeding himself (metaphorically and literally) on the Great Books, devouring the canon page by page. His rat lust leads him to Moby-Dick, Don Quixote, and Finnegans Wake. "My favorites were the Modern Library editions," Firmin says. "Recite them, then, say them slowly aloud and let them break your heart. Oliver Twist. Huckleberry Finn. The Great Gatsby. Dead Souls. Middlemarch. Alice in Wonderland. Fathers and Sons. The Grapes of Wrath. The Way of All Flesh. An American Tragedy. Peter Pan. The Red and the Black. Lady Chatterley's Lover."

Firmin takes in the great stories and then, like Quixote himself, the sharp edges of his real life soften, and he regrets staying safely inside the artificial world of books. "The truth is, I have never been right in the head," Firmin admits. "Only, I don't charge windmills. I do worse: I dream of charging windmills, I long to charge windmills, and sometimes even imagine I have charged windmills."

As the author says of the rat's literary habits, "He begins to read because he is lonely, and he is lonely because he is puny and shunted from his family, a minor freak from the get-go. As he reads he becomes at once less lonely—he has the companionship of books—and more alone—he grows both more freakish and more conscious of his solitude."

Firmin takes a dark turn as the plot centers on the "renovation," or destruction, of Scollay Square, where Pembroke Books sits. With the impending demise of the bookstore, Firmin's fascination with its owner dims, and he takes up with Jerry Magoon, a down-and-out science fiction writer who lives above the store. Firmin and Magoon become the best of friends—and then, suddenly, the characters stumble into true tragedy.

"A curious thing happens when we endow animals with human traits, whether dancing dogs in tutus or monkeys in little jackets," says Savage. "They become parodies, not ridiculous animals so much as ridiculous humans.… Firmin can deliver the most heartbreaking statements, and because he is a rat, they become simultaneously heartbreaking and ludicrous."

On the other end of the animal-lit spectrum is Klinkenborg's naturalist treaty Timothy, which is uniquely and utterly un-Orwellian. In Timothy, the reader comes upon the deeply carved and finely imagined caverns of a tortoise's mind. Based upon Gilbert White's observations in his Natural History of Selborne, first published in 1789, Klinkenborg investigates the world in reverse: the tortoise observing the naturalist.

The novel's narration is oddly animalistic, characterized by simple sentences and poetic stutters: "When autumn pinches, I dig. November darkens, fasting long since begun.… No rush. No rush. Ease in again. A last fitting. Air hole open. Stow legs. Retreat under roof of self. Under vault of ribs and spine."

In Timothy, Klinkenborg does not journey into the natural world simply to shed new light on human life or to poke fun at the politics of people, but, rather, to allow readers to more completely consider that animal world as parallel to our own. "The two great motives of love and hunger yaw back and forth through Selborne, driving human and beast alike," he writes.

When asked about the separation of humans and animals, Klinkenborg is unambiguous. "They're not separate at all, not in any way. Humans are animals and are subject to the fundamental environmental and population constraints that all other species on this planet are subject to," he says. "What sets us apart is that we love to believe we're not subject to those constraints."

Whether the latest animal protagonists draw readers' attention to the startling similarities or the cruel differences between man and beast, it is clear that the legacy of Orwell's animal satire remains secure. Contemporary writers like Savage and Klinkenborg continue to use the animal kingdom to expose and investigate the human condition—borrowing from the cat and rat, tortoise and cow, to expose our flaws, fractures, and infinite follies.

Joe Woodward is the author of Small Matters: A Year in Writing.