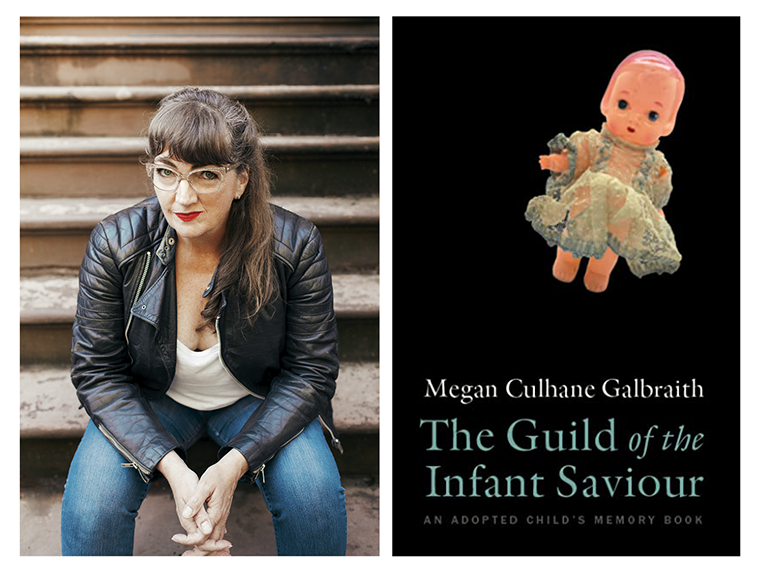

Megan Culhane Galbraith, author The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book, published by Mad Creek Books/Ohio State University Press in May 2021. (Credit: Beth Mickalonis)

Prologue

Children play to control the world. When I was a child, I wanted to control my world because as an adoptee I felt I had no control. I created small universes populated by all sorts of figures: friends to have tea with, monsters to defeat, and new miniature realms to explore. It was empowering to make all the decisions, so I built dioramas and imagined myself into another life. It didn’t matter that the stage was tiny. These were worlds into which I could disappear.

I’d just given birth to my first son when I found my birth mother, Ursula. I have changed her name to respect her request for privacy. I was twenty-nine years old. I learned she’d become pregnant with me and was sent away to a Catholic home for unwed mothers—The Guild of the Infant Saviour—in Manhattan.

Years later, I began playing with a tin dollhouse I’d found at a local antique shop; A ’60s-era Louis Marx “Marxie Mansion” of the same time period in which Ursula was sent away to have me. I found a set of dolls from that era called The Campus Cuties. They were made from molded hard plastic like the toy soldiers of the time. I purchased some from eBay and then Etsy. The dolls had vacant stares and bullet bras like tiny, hyper-sexualized blank slates. Little girls had painted some of my favorites: their eyes black blobs; their clothing peeling off. I find them weirdly endearing. Their arms and legs are frozen in position and their names imply the roles society cast for women in the ’50s and ’60s—“Nighty Nite,” “Lodge Girl,” “Stormy Weather,” “Dinner for Two,” and “Shopping Anyone?” If The Campus Cuties were rendered in the flesh they’d have 40-inch inseams, 12-inch waists, and breasts the size of beach balls.

I hadn’t been given dolls to play with as a child—no Barbie, or Baby Alive. I had no doll to feed, nor did I ever change a doll’s diaper. Yet here I was a grown woman (a feminist!) besotted with these booby, leggy, plastic dolls. I was also in love with the tiny, delicate baby dolls. They too were made from plastic, although they were fragile as eggshells and the size of a three-month-old fetus. I collected them with obsessive zeal.

The dollhouse became a visual art project called The Dollhouse. I staged the Cuties and babies in household situations and photographed them from the outside looking in. I realized it was a voyeuristic way of seeing a situation from an angle of removal. It gave me the space I needed to examine my adopted life through a different lens. It emphasized a dystopia perhaps that was right there before my eyes.

I’d been the subject of many photographs—my dad being the photographer—but now, playing with these dolls, I realized I’d also been an object: a doll. Behind the lens of my camera, I am the director of my narrative. I’ve reclaimed a sense of control. Play calmed me down, allowed me to turn off my brain, and when I did, thoughts flooded in; memories returned. I became curiouser and curiouser. I began to ask uncomfortable questions. A window opened to a new way of seeing my reality. Ursula and I have now known each other for nearly twenty-five years, and after hearing her tell me stories—shot through her lens of memory, grief, and trauma—I realize we have more in common than just the circumstance of my birth: we had both disappeared into our fantasies. Mine was tiny, imaginary, and voluntary; hers was all too real.

We’d both been pregnant with shame.

“No one gets a dollhouse to play at reality,” said the child psychologist Erik Erickson, “but reality seeps in everywhere when we play.”

As an adult, I see myself in early photographs and can identify the feeling of being fragile, helpless, and adrift. Like many adoptees, I’ve moved through depression, suicidal ideation, an eating disorder, anxiety, and sexual acting out. I’ve identified gashes of grief and shame: wounds I’d been licking instead of healing.

Adoption is what author Nancy Verrier called “the primal wound,” and the resulting feelings of abandonment, shame, and loss are due to the severed connection between birth mother and child when a baby is taken away.

“Children are innocent before they are corrupted by adults,” said Erickson, “although we know some of them are not and those children—the ones capable of arranging and rearranging the furniture and dolls in any dollhouse—are the most dangerous of all. Power and innocence together are explosive.”

I realize now that I don’t need to apologize for my exist ence.

The Dollhouse became a lens through which I could see my birth mother and myself. I could safely question my personal history and interrogate the myths of adoption, identity, feminism, and home. As an adopted child, I’d felt like a thing to be played with instead of a person with her own identity. I’d felt looked at, but not seen. I liked the idea of reclaiming what home meant to me by playing in my dollhouse because I’d never felt truly at home anywhere, not even in my own body.

Holding those fragile plastic babies in the palm of my hand made me realize I had to hold myself with the same delicacy.

Play helped me unlock ways of expressing the paradox of my identity as an adoptee while exploring intergenerational trauma, erasure, abandonment, and the myths and family lore that factor into many adoptees’ origin stories. The Dollhouse photos in this book are recreating the original photos I curated from my Adopted Child’s Memory Book, among other places. The original photos—like artifacts—appear at the end of each essay.

In The Dollhouse I created a world where women rule on a 1:12-scale: a portal to imagine myself into my birth mother’s life and her into mine.

Our stories are fractured.

Our narratives double back on themselves like an ouro boros swallowing its tail.

From Megan Culhane Galbraith’s The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book, used by permission of Mad Creek Books, an imprint of The Ohio State University Press.

Read Megan Culhane Galbraith’s essay about writing The Guild of the Infant Saviour: An Adopted Child’s Memory Book in the November/December 2021 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine.