This is the inaugural installment of Inside Indie Bookstores, a new series of interviews with the entrepreneurs who represent the last link in the chain that connects writers with their intended audience. Once the authors, agents, editors, publishers, and salespeople have finished their jobs, it's up to these stalwarts to get books where they belong: into the hands of readers. News of another landmark bookstore closing its doors has become all too common, so now is the perfect time to shine a brighter light on the institutions that mean so much to the literary community. Post a comment below to share your thoughts about a favorite indie bookstore.

The first thing customers notice when they enter Square Books—apart from the customary shelves and tables overflowing with hardcovers and paperbacks—is the signed author photographs. There are hundreds of them, occupying nearly every vertical surface not already taken up by bookcases. They cover the walls and trail up the narrow staircase to the second floor, framing windows and reaching all the way to the fourteen-foot-high tongue-and-groove ceiling. Most of the photos are black-and-white publicity shots, the kind publishers send with press kits, but there are also large-format, professional ones—of Larry Brown, Barry Hannah, Richard Ford, and others. Many have that spare yet beautiful quality of something Eudora Welty might have taken. Collectively, they comprise an archeological record of this place's luminous history—all the authors have passed through these doors—as well as a document of the important role that this particular institution has had in promoting writers and writing.

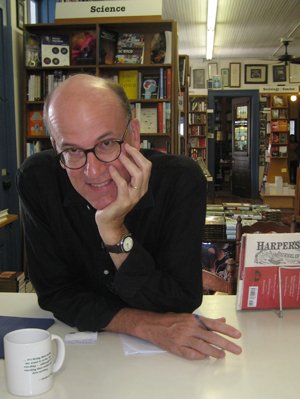

Richard Howorth, the store's owner, would modestly deny having had a hand in any of the number of literary careers that have sprung from the fertile soil in this part of the country, but the honest truth is that Square Books has served as a nurturing place for writers—as a "sanctuary," to borrow a word from William Faulkner, another Oxford native—for more than thirty years now. He and his wife, Lisa, opened the first store in 1979. Seven years later they moved into their current location, formerly the Blaylock Drug Store, after buying the building. Since then, they've opened two other shops: in 1993, Off Square Books, which specializes in used books, remainders, and rare books and serves as the venue for store events and the Thacker Mountain Radio program; and, in 2003, Square Books, Jr., a children's bookstore. Howorth also helped establish the Oxford Conference for the Book, which brings together writers, editors, and other representatives from the publishing world each spring for public readings, roundtables, and panel discussions on writing and literacy. This year, as part of the seventeenth annual event, the conference will celebrate the legacy of Barry Hannah.

I made my first literary pilgrimage to Oxford nearly a decade ago. At the time, I was running Canterbury Booksellers, a small independent bookshop in Madison, Wisconsin. Invariably, whenever authors visited our store, one of the topics we'd end up discussing was where they were headed next or where they'd just been. Square Books was always mentioned as a place they one day hoped to go, were looking forward to going, or couldn't wait to get back to. Partly this has to do with its lineage, for few places can claim to have hosted readings for such varied and important authors as Etheridge Knight, Toni Morrison, Allen Ginsberg, Alice Walker, Alex Haley, George Plimpton, William Styron, Peter Matthiessen, and others. And partly it has to do with the Howorths themselves, who, despite the cliché about Southern hospitality, make all authors feel as if they were the first to visit the store.

This was certainly the case for me. Even though I wasn't reading, and even though I hadn't been back to town in almost ten years, I was welcomed with enormous generosity when I arrived. For two days I was given the grand tour, including a dinner with local writers at the Howorths' house, a walk through Faulkner's home, a trip to the Ole Miss campus to see the bronze statue of James Meredith under a marble archway in which the word courage is carved into the stone, as well as an oral history of what took place in Oxford during the Civil War as we drove through the shady neighborhoods of town.

No person could have been a better guide to the literary and historical roots of Oxford. Howorth grew up across the street from Faulkner's home (in the house where the bookseller's father, a retired doctor, still lives). Faulkner's sister-in-law used to chase Richard and his brothers off the property for pestering her cow and causing mischief. All the Howorth brothers still reside in town—one a judge, one a retired lawyer, one an architect, and one a retired admissions director at the University of Mississippi. In addition to his thirty years as a local bookseller, Richard, the middle brother, also just finished his second term as mayor of Oxford.

It was with this same generosity of spirit that Howorth agreed to talk with me at Square Books one afternoon. We sat upstairs, at a small table in an out-of-the-way corner. I chose the spot because it seemed secluded—though, coincidentally, we were between the Faulkner and Southern Literature sections. Howorth commandeered the espresso machine and made us cappuccinos before we settled in to chat, fixing us our drinks himself. He is a man quick to laugh, and despite having spent the past three decades as a bookseller and the last eight years in public office, seems largely optimistic about the world. Or, rather, has learned to appreciate life's quirks, mysteries, and small pleasures.

How did you come to bookselling?

Deliberately. I wanted to open a

bookstore in my hometown, so I sought work in a bookstore in order to learn the

business and see whether it was something that I would enjoy doing, and would

be capable of doing.

The apprentice model.

Yes. Lisa and I both worked in the

Savile Bookshop, in Georgetown, for two years. In the fifties and sixties it

was a Washington institution. It was a great old store. The founder died about

ten years before we arrived. It had been through a series of owners and

managers, and by the time we were working there it was on its last leg. It was

also at the time that Crown Books was first opening in the Washington

suburbs—it was the first sort of chain deep-discounter. The Savile had this

reputation as a great store, but it was obviously slipping. We were on credit

hold all over the place. So it ended up being a great learning experience.

Then you came back here with the

intention of opening Square Books?

Sure. We opened the first store in the

upstairs, over what was, I think, the shoe department of Neilson's Department

Store. Back then the town square was so much different from what it is today,

and commerce was not so terribly vital. It was certainly viable, but the

businesses didn't turn over very much because the families that owned the

businesses usually owned the buildings. Old Mr. Denton at his furniture store

didn't care if he sold a stick of furniture all day; it was just what he did,

run his store. So when I came home I knew I wanted to be on the square, and I

just couldn't find a place. My aunt owned the building where Neilson's had a

long-term lease on the ground floor, but there were three offices

upstairs—rented to an insurance agent, a lawyer, and a real estate agent who

were paying forty dollars, thirty dollars, and thirty dollars a month,

respectively, for a total of a hundred dollars. So my initial rent was a hundred

dollars a month.

Did you have a particular vision

for this store from the beginning, or did it change over time?

The initial vision is still very much

what the store is today. I wanted it to serve the community. Because of

Mississippi's distinct history and character, as well as social disruptions,

the state—and Oxford, in particular, due to the desegregation of the

university in 1962, when there was a riot and two people were killed—was

regarded as a place of hatred and bigotry. And I knew that this community was not that. I knew that there were a lot of other

people here who viewed the world the same way my family did, and my instinct

was that people would support the store not just because they wanted to buy

books or wanted a bookstore here, but because they knew—not to overstate

it—that a bookstore would send a message. That we're not all illiterate, we're

not all...it said something about both the economic and cultural health of the

community.

Has that happened?

The university, for instance, has made

a lot of progress—there's now a statue of James Meredith; there's now an

institute for racial reconciliation at the university. And most young people

today know what the civil rights movement was, but they don't know the specific

events and how tense and dramatic and difficult all of that was at that time.