Invented by a trio of Wisconsin printers and inventors in the late 1860s, the modern typewriter was a fixture in American homes and offices and the primary tool for writers through the 1970s. With the advent of the personal computer in the 1980s, of course, the typewriter was marginalized as a curiosity, but in the past several years a few designers have created a variety of gadgets and software that resurrect the charm, physicality, and writing benefits of the typewriter for the digital age.

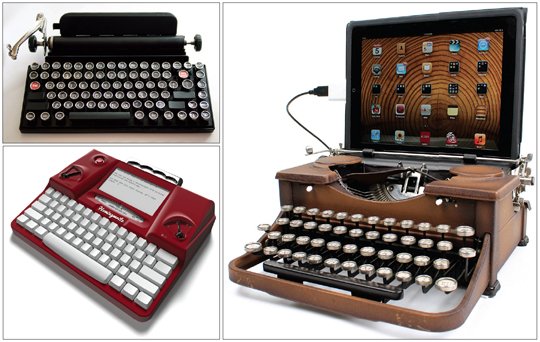

The USB Typewriter, created by Jack Zylkin, is one of the products that pay homage to that lionized, endangered, and, for some, still preferable writing machine. The USB Typewriter is a kit of electronica that, when installed on a typewriter, sends whatever is typed on the machine to an attached digital device—a computer, tablet, or smartphone—where it is stored as electronic, and thus editable and uploadable, text. The converted typewriter still works on its own, in the traditional fashion, with or without a device attached. Zylkin began tinkering with his own typewriter in 2009, simply out of love for the machine and a wish to rescue it from obsolescence; it wasn’t until he officially introduced his creation to the public, in 2010, that he fully realized what it could mean for writers. “For me, it’s all about the magic of typewriters and how wonderful they are—I just like working on them,” Zylkin says. “But they represent a whole way of writing that is being forgotten. There are a lot of writers out there who won’t write on anything except a typewriter, and I don’t think it’s necessarily because they have an appreciation for the engineering of a typewriter; I think it’s because that’s how they write. They really value the way it pushes them to think and develop their writing and the inner state they can get into.”

This same idea seems to be the impetus behind a recent rash of applications and software features that simulate various aspects of the typewriter. Hanx Writer is an app (incidentally, one created by actor and writer Tom Hanks, who recently signed a deal with Knopf to publish his typewriter-inspired debut story collection) that “re-creates the experience of a manual typewriter, but with the ease and speed of an iPad.” The app mimics the appearance, font, and sound of a typewriter, and creates PDF documents of the text.

Many word-processing programs, including Microsoft Word, Scrivener, and iA Writer, have typewriter-esque full-screen modes wherein, with the click of a mouse, the myriad control panels, navigation bars, search fields, and editing ribbons that normally clutter a computer user’s field of vision—and, subsequently, her psyche—disappear. Still, in these cases, the clutter remains merely out of sight, an easy click or swipe away. Designer Adam Leeb and developer Patrick Paul eliminated that temptation with the Hemingwrite, a device they launched last fall as “the overengineered typewriter for the twenty-first century.” The Hemingwrite seems like the logical successor to the electric typewriter, had the latter not been so spectacularly eclipsed by the computer: It’s a self-contained, highly portable digital device that offers nothing except word processing with backup to the cloud. It has a keyboard, a six-inch e-ink screen with backlight for uncompromised daylight viewing, and a projected six-week battery life (just in case a user cares to, as described on the website, “pull a Thoreau” and disappear into the woods). It also boasts a storage capacity of approximately one million pages. “On design decisions, we say yes to anything that makes it a better writing tool, and no to anything that makes it more cross-functional like a laptop,” says Paul.

For both Paul and Zylkin, one of the benefits of modernizing the typewriter is separating the processes of writing and editing, which computers have not traditionally supported. Even though his own writing consists mostly of personal correspondence, Zylkin notes, “I’m constantly reviewing what I’m writing as I’m writing it, and constantly going back and reviewing and editing it. What I should do is just write, not look back and second-guess.” Paul, of Hemingwrite, is of a similar mind. “I personally struggle with too much premature editing,” he says. “I think ideas happen while you are writing, and composition, for me at least, needs to be decoupled from editing.”

This is a major selling point for Typing Writer, an app created by Rumpus editor Stephen Elliott and designers Eli Horowitz, Russell Quinn, and Chris Ying that came out last summer. On the app’s website, Elliott writes, “We felt we were more productive on a typewriter because we had to keep moving forward.... If we made a mistake, we kept typing. If we wanted to rearrange the information, we had to start over. With the word processor we’ve lost some of the immediacy. It’s too easy to delete, to cut and paste.” Typing Writer does allow “deletions,” but not with the use of a backspace key; rather, a user can touch a finger to the screen, which leaves a white smudge mark over an error—the digital equivalent of Wite-Out.

With the growing popularity of harnessing typewriter technology, designers and typewriter enthusiasts continue to experiment with new products. Brian Min, a California-based game developer, is currently building the Qwerkywriter—an external keyboard with USB and Bluetooth connectivity that looks just like a manual typewriter keyboard—which is slated to come out in summer 2015. Meanwhile, Zylkin is working on a self-contained version of the USB Typewriter, one that is battery powered and can store text on its own. He also continues to sell USB typewriters that he’s already built, as well as the do-it-yourself conversion kits that are compatible with a variety of manual machines. Customers can visit the website, enter their typewriter’s make and model, and receive a custom kit for their machine. A screwdriver, glue, and an emery board are all a user needs to create his own twenty-first-century typing machine.

And while Zylkin continues to be driven by the engineering of the machines he’s helping save, the popularity of his USB Typewriters has also helped him find inspiration in the creative lives of those who use them most. The wife of Pulitzer Prize– and Academy Award–winning writer Larry McMurtry recently asked Zylkin to help usher McMurtry into the Internet age by building him a USB Typewriter. According to Zylkin, McMurtry—who notably thanked his Swiss-made Hermes 3000 typewriter in his Golden Globe acceptance speech—had refused to touch anything computerized before receiving his hybrid machine.

“I don’t understand the writer’s psyche, so I can’t pretend to know what about a typewriter helps or hurts as compared with writing on a computer keyboard,” Zylkin says. “But if that’s what writers think is the magic mojo in their writing, then I want to help provide that for them.”

Rachel Lieff Axelbank is an editorial assistant at the Brooklyn Quarterly. She lives in New York City.