The most important books in my life have arrived by providence. As a teenager, I stumbled upon one enormous literary discovery after another. My father gifted me his worn paperback editions of Galway Kinnell and James Wright when I was just fourteen; at sixteen, I found a coffee-stained copy of Raymond Carver’s Where I’m Calling From (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1988) abandoned on a table at a local café. The work of American short story writer Andre Dubus arrived in a similarly serendipitous way.

During the bitterly cold February of my twenty-third year, I made a Sunday pilgrimage to an independent bookstore. It was a bland store—utilitarian metal bookshelves, unremarkable carpeting, humming fluorescent lights—but I could always count on the staff’s recommendations. I had never heard of Dubus before, and it would be years of mispronunciation before I learned that his last name rhymes with “abuse,” like “duh-byoos.” But that day, Dancing After Hours (Knopf, 1996) leapt out at me.

I plucked the book from the shelf. On the back cover, comparisons to Anton Chekhov and Raymond Carver caught my eye, as did mentions of the obsessions I would soon come to understand were hallmarks of Dubus’s work: tenderness, hurt, courage, redemption. I opened the paperback and submitted it to a test I would later discover Dubus himself was fond of: I read the opening lines of a few stories. By the end of the first line of “The Timing of Sin,” I was ready to plunk down my twelve dollars: “On a Thursday night in early autumn she nearly committed adultery, was within minutes of consummating it, or within touches, kisses; it was difficult to measure by time or by her mouth and tongue and hands, or by his.”

Over the next week, I carefully read each story in Dancing After Hours; over the following weeks, I reread the stories. And it wasn’t long before I had collected and read everything Dubus had written. I quickly discovered that his work was not easy; the stories were fraught with hard moments of loneliness, heartache, violence, adultery, rape, murder, and abortion. “I think honest writers write about what bothers them,” Dubus once said of his choice of subject matter.

Though some have found his narratives too dark or brooding, I was startled and impressed by the richness of the characters Dubus sketched. He populated his stories with complex characters that are neither all good nor all evil, neither all right nor all wrong—but none of them seemed completely beyond the possibility of redemption. This touch of kindheartedness amazed me. As I read, his characters became a part of my consciousness and my understanding of humanity: a young boy haunted by the urge to masturbate (“If They Knew Yvonne”); a young girl struggling with her weight (“The Fat Girl”); a wife caught in the moment of accepting and dealing with the consequences of her failed marriage (“Adultery”); a father hypnotized by the false hope promised by revenge (“Killings”); and another father, this one divorced, torn between doing what is “right” and protecting his daughter (“A Father’s Story”). With a delicate touch that many writers lack, Dubus could skim the surface of sentimentality even as he graced his characters with quiet dignity.

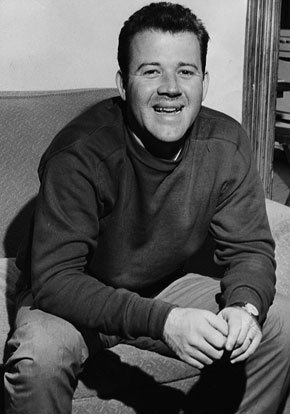

I learned later that like so many of his inscrutable yet familiar characters, Dubus himself was a complex man. A thrice-divorced devout Catholic who fathered six children—including Andre Dubus III, the author of House of Sand and Fog (Norton, 1999)—by two women, Dubus was a barrel-chested ex-marine who liked a stiff drink and the occasional bar fight, but had a propensity to cry during schmaltzy movies. He could be distracted and distant at times, but many describe him as one of the most tender, sentimental people they’ve ever known.

I understand now that his writing has been a twofold gift in my life. As a writer, the short stories taught me about compression and point of view, and as a human being they gave me a deeper understanding of empathy and compassion.

![]()

Perhaps more than any other American writer of his generation, Andre Dubus was fiercely devoted to the short story. “I love short stories because I believe they are the way we live,” Dubus once wrote. “They are what our friends tell us, in their pain and joy, their passion and rage, their yearning and their cry against injustice.”

While his stories would eventually earn him fellowships from the Guggenheim and MacArthur Foundations, as well as the PEN/Malamud Award, the Rea Award for the Short Story, the Jean Stein Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and nominations for a National Book Critics Circle Award and a Pulitzer Prize, Dubus struggled to find a foothold in a publishing world dominated by novels. His devotion to the short story kept him off the best-seller list, and even today Dubus remains largely unknown to the general public, praised instead as a “writer’s writer.” New readers are likely to have discovered Dubus by way of In the Bedroom and We Don’t Live Here Anymore, two award-winning films adapted from his stories. Yet Dubus has influenced scores of today’s short story practitioners, including Chris Offutt, Robert Olmstead, Tobias Wolff, and Monica Wood, and is greatly admired by E. L. Doctorow, John Irving, Stephen King, Elmore Leonard, and John Updike.

Born in Lake Charles, Louisiana, in the summer of 1936, Dubus was raised and schooled in the Catholic South. He remained involved with the church throughout his life, and religious themes are often reflected, along with his own personal experiences, in the moral and ethical dilemmas his characters struggle to navigate. Dubus told Walker Percy biographer Patrick Samway, in an interview published in America magazine in 1986, that he believed his Catholicism heightened his “sense of fascination and compassion.” If many people view the Catholic faith in black and white, Dubus saw it as multicolored. “If there were no sin, there wouldn’t be art,” he once quipped in an interview in Glimmer Train.

Dubus was drawn to writing at an early age and reveled in the work of Joseph Conrad and Ernest Hemingway. He began publishing stories while attending McNeese State University in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and continued writing even after he joined the United States Marine Corps in 1958. When Dubus eventually realized he had become a marine to prove his manhood to his father, he left the military (where he had risen to the rank of captain) for the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. In Iowa, Dubus studied under Richard Yates and Kurt Vonnegut, two writers who would later become staunch supporters of his work. After earning his MFA in 1965, Dubus drew on the material he’d gathered during his years as a peacetime marine to write the only published novel of his thirty-year writing career: The Lieutenant (Dial Press, 1967). By the time he joined the faculty at Bradford College in Haverhill, Massachusetts, in 1966 (where he remained until his retirement in 1984), Dubus had discovered the Russian short story master Anton Chekhov. When he realized that Chekhov’s story “Peasants” managed to squeeze a year in the life of a poor Russian family into just thirty pages, Dubus became infatuated by the idea of condensing tales that were novelistic in scope into short stories or novellas. He trashed the second novel he had spent months writing and dedicated himself to the short story. “My conscience is Chekhov,” Dubus told interviewer Robert Nathan in the February 1977 issue of Bookletter. “I write with him on my shoulder.”

Dubus’s prowess in narrative compression is legendary. Andre Dubus III has written that his father’s story “Waiting,” about the hollow ache experienced by a woman widowed by the Korean war, took fourteen months to write and was more than one hundred pages in early manuscript form. But when the story was published in the Paris Review, it spanned a mere seven pages.

Though Dubus slowed down his writing process in later years and wrote fewer drafts, he typically pared back his stories over the course of successive versions. After he had taken a piece through as many written drafts as he could, Dubus would read the story aloud into a tape recorder, a practice he began as a student in Iowa. Dubus said that listening to these recordings allowed him to catch details he had missed, such as repetitions and jarring rhythms. “It’s physical, less abstract, when you use your voice and ears,” Dubus said of his listening method in a 1998 Yale Review interview. Fiction writer Peter Orner remembers that Dubus had an astonishing capacity for listening. Orner, the author of The Second Coming of Mavala Shikongo (Little, Brown, 2006), attended a weekly gathering of writers that Dubus hosted at his home every Thursday night during the later years of his life. “Andre led by listening—not talking, but listening,” Orner remembers. “I have never met anybody who listened like Andre. When you’d read a story on Thursday night, he’d lean back a little in his chair and close his eyes and listen so hard. I remember watching him listen and feeling ashamed I couldn’t listen like that.”

Yet even as he whittled his stories down to their cores, Dubus infused them with both psychological breadth and emotional immediacy. Typically, he begins his stories on the cusp of a powerful incident in a character’s life, as in the first lines of “The Winter Father”: “The Jackmans’ marriage had been adulterous and violent, but in its last days, they became a couple again, as they might have if one of them were slowly dying.” Dubus moved beyond the old adage “show, don’t tell” to create his own authorial maxim: Don’t tell everything. His flowing, poetic sentences can rush through several years in three paragraphs before screeching to a halt and moving through a ten-minute conversation with excruciating detail and insight.

As Dubus’s reputation grew, his stories were published in literary quarterlies, from Black Warrior Review to Ploughshares and the Paris Review, and occasionally in magazines such as Harper’s and the New Yorker. But even as major publishing houses waved book deals and big advances under his nose in exchange for the promise of a novel, Dubus remained steadfastly dedicated to the short story. It was no easy stand to take for a writer who wanted his stories published in book form. After the publication of The Lieutenant, Dubus waited eight rejection-filled years before the Boston-based independent publisher David R. Godine published his first story collection, Separate Flights, in 1975.