In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 242.

In the fourteenth century the Kashmiri poet Lal Ded, or Lalla, wrote:

I didn’t trust it for a moment

but I drank it anyway,

the wine of my own poetry.It gave me the daring to take hold

of the darkness and tear it down

and cut it into little pieces.

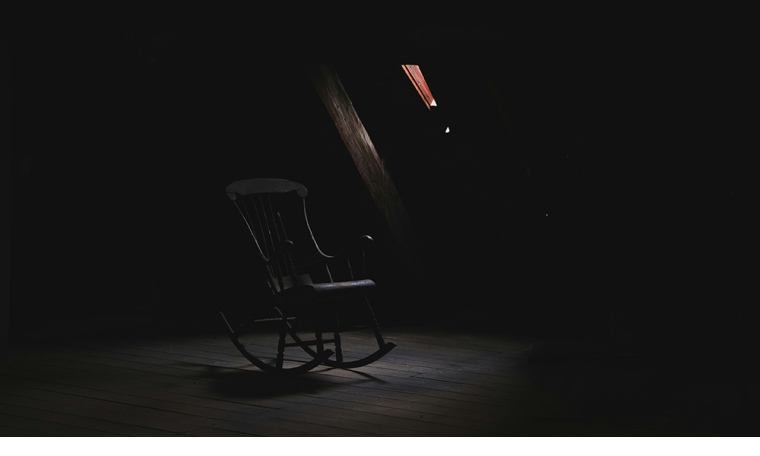

Grief has the potential to destroy our sense of self, our most basic relationships, our trust in the world. It can break apart our sense of meaning, love, connection. When we make a poem, we work to shape that darkness that Lalla wrote about six centuries ago. By tearing it into little pieces and then moving those pieces around to make a poem, we are able to remain in the experience, while still holding it at a workable distance.

We know that life can be chaotic and overwhelming. When we make art, we create order and we give our experience meaning. Or it’s more accurate to say, we search for its meaning. In every authentic poem, there is a search to discover something we didn’t know before. We allow the poem to teach us, to change us. It’s a mutual process. As we shape the poem, the poem shapes us. By poem’s end, we are not the same. This transformation is the deepest, most fundamental reason we write. Not just writing about grief and loss but writing about anything. We write a poem to be changed, transformed, enriched, enlarged.

Some of our losses are current and immediate. We may be in the first shock of the death of someone we love or the rupture of an important relationship. We may have just had an accident or the onset of serious illness. There is also other suffering that we’ve carried over time and never been able to put down or come to terms with.

One of those for me has been my debilitating first marriage and the destructive impact my husband had on our child. I tried to grapple with my feelings about that for forty years and through at least forty failed poems and a failed novel. But sometimes (for me at least) it takes a lot of rendering to discover the poem in the experience. And one day I saw a tattooed man wheeling his baby in a stroller and that image gave me the central metaphor of embodiment. Finally, I was able to write the poem that would allow me to see with clarity my own past, my ongoing struggle, and, finally, my daughter’s profound love and courage.

Indigo

As I’m walking on West Cliff Drive, a man runs

toward me pushing one of those jogging strollers

with shock absorbers so the baby can keep sleeping,

which this baby is. I can just get a glimpse

of its almost translucent eyelids. The father is young,

a jungle of indigo and carnelian tattooed

from knuckle to jaw, leafy vines and blossoms,

saints and symbols. Thick wooden plugs pierce

his lobes and his sunglasses testify

to the radiance haloed around him. I’m so jealous.

As I often am. It’s a kind of obsession.

I want him to have been my child’s father.

I want to have married a man who wanted

to be in a body, who wanted to live in it so much

that he marked it up like a book, underlining,

highlighting, writing in the margins, I was here.

Not like my dead ex-husband, who was always

fighting against the flesh, who sat for hours

on his zafu chanting om and then went out

and broke his hand punching the car.

I imagine when this galloping man gets home

he’s going to want to have sex with his wife,

who slept in late, and then he’ll eat

barbecued ribs and let the baby teethe on a bone

while he drinks a dark beer. I can’t stop

wishing my daughter had had a father like that.

I can’t stop wishing I’d had that life. Oh, I know

it’s a miracle to have a life. Any life at all.

It took eight years for my parents to conceive me.

First there was the war and then just waiting.

And my mother’s bones so narrow, she had to be slit

and I airlifted. That anyone is born,

each precarious success from sperm and egg

to zygote, embryo, infant, is a wonder.

And here I am, alive.

Almost seventy years and nothing has killed me.

Not the car I totaled running a stop sign

or the spirochete that screwed into my blood.

Not the tree that fell in the forest exactly

where I was standing—my best friend shoving me

backward so I fell on my ass as it crashed.

I’m alive.

And I gave birth to a child.

So she didn’t get a father who’d sling her

onto his shoulder. And so much else she didn’t get.

I’ve cried most of my life over that.

And now there’s everything that we can’t talk about.

We love—but cannot take

too much of each other.

Yet she is the one who, when I asked her to kill me

if I no longer had my mind—

we were on our way into Ross,

shopping for dresses. That’s something

she likes and they all look adorable on her—

she’s the only one

who didn’t hesitate or refuse

or waver or flinch.

As we strode across the parking lot

she said, O.K., but when’s the cutoff?

That’s what I need to know.

If your grief is fresh, you may need to write pages and pages. But for some people that would be overwhelming, so you may want to follow Lalla’s example, and break that darkness down into little pieces. You might want to write about your wife’s shoes, the way she wore down one side of the heel with her determined stride. Or the view out the window of the high-rise that your mentor lived in—how when you’d visit, you’d sometimes get up in the night and look out the window at the lights of the cars and taxis going by. It’s a tender paradox that remembering is its own kind of healing.

Poetry gives us a way to order chaos and thus feel some equilibrium in times of great tumult and disruption: The poet Gregory Orr knows this all too well. When he was a child, he shot and killed his younger brother in a hunting accident. His book Poetry As Survival (University of Georgia Press, 2002), is extremely articulate, not only about how poetry can help us to survive, but about many other aspects of the craft as well. Orr writes, “the elaborative and intense patterns of poetry can...make people feel safe...the enormous disordering power of trauma needs or demands an equally powerful ordering to contain it, and poetry offers such order.”

The Irish literary critic Denis Donoghue put it succinctly: “The passions may be terrible, but the syllables are a relief.”

Ellen Bass’s most recent collection, Indigo, was published by Copper Canyon Press in 2020. Among her other poetry books are Like a Beggar (Copper Canyon, 2014), The Human Line (Copper Canyon, 2007), and Mules of Love (BOA Editions, 2002). Her poems appear frequently in the New Yorker, the American Poetry Review, and many other journals. Among her awards are fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and four Pushcart Prizes. A Chancellor Emerita of the Academy of American Poets, Bass founded poetry workshops at Salinas Valley State Prison and jails in Santa Cruz, California, and teaches in the MFA writing program at Pacific University. This Craft Capsule is adapted from her online Living Room Craft Talks. To learn more visit ellenbass.com.

“Indigo” is reprinted from Indigo: Poems. Copyright © 2020 by Ellen Bass. Used with the permission of The Permissions Company, LLC on behalf of Copper Canyon Press, coppercanyonpress.org.

image credit: Anthony Delanoix