For a journal that was established the same year Walt Whitman died and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes was first published, the Sewanee Review has come a long way. Launched in 1892 by teacher and critic William Peterfield Trent as a journal of “General Theology, Philosophy, History, and Literature,” the publication—which now primarily publishes poetry, fiction, and nonfiction—has chronicled the changing American literary landscape over the past hundred and twenty-five years. Having published many of the most notable writers of the twentieth century, including poets T. S. Eliot and Sylvia Plath and fiction writers Flannery O’Connor, Saul Bellow, and William Faulkner, today the journal celebrates its long literary history with the release of its five hundredth issue.

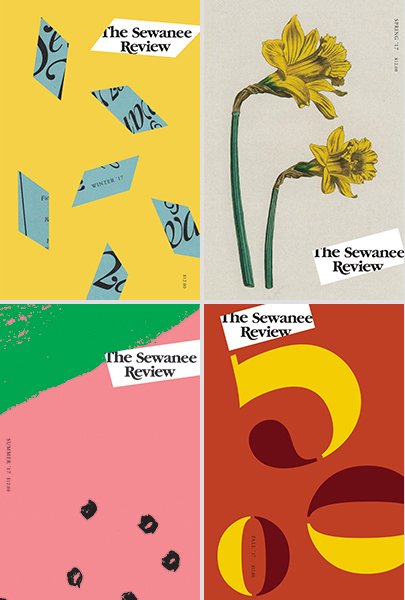

The most recent issues of the Sewanee Review, edited by Adam Ross.

The new issue also caps off writer Adam Ross’s first year as the journal’s editor. In 2016 Ross, the author of the novel Mr. Peanut (Knopf, 2010) and the story collection Ladies and Gentlemen (Knopf, 2011), succeeded editor George Core, who had steered the publication for forty-three years. Ross took on the challenge of revamping the journal, which had fallen in prominence over the years; its subscription numbers had dwindled to just a few hundred. Other long-running literary quarterlies such as the Southern Review and Virginia Quarterly Review both have circulations of a few thousand.

Ross focused on modernizing the journal and reaching more readers, a process he admits has been bumpy at times. “When you redesign a magazine, build a new website, bring on an entirely new stable of writers, switch your submissions platform from snail mail to electronic, take over your subscriptions from your publisher, hire a completely new staff—all recent Sewanee graduates, I’ll add—all in a single year, what could possibly go wrong?” Ross says. “Let’s just say we made lots of omelets and gallons of lemonade and failed to launch.” Ross recalls how days before his first issue came out, the staff narrowly avoided paying significant fees to the postal service because the cover read Sewanee Review instead of The Sewanee Review. “There was some last-minute scrambling with our designers, let me tell you,” says Ross.

While the review might have been a bit harried behind the scenes, the issues themselves have offered smart, fresh takes on the world of contemporary letters. The editors have published new voices such as Sidik Fofana and Jen Logan Meyer, as well as more established ones such as poets Mary Ruefle and A. E. Stallings and prose writers Francine Prose and Lauren Groff. The contributor pool is also more diverse than ever. “Perhaps I’m most proud of the fact that it’s the first time in the review’s history that a volume has been authored by a majority of women writers,” says Ross.

In his first issue as editor, Ross wrote a piece, “The State of Letters,” laying out the journal’s editorial values: The editors will resist nostalgia for literature of the past, which he notes was, “from the point of view of gender and ethnicity, a comparative monoculture,” and look for literature that can “recalibrate how we see the world and ourselves.” Ross avoids any prescriptions on what kind of work the journal will publish. “Our primary tool is still taste,” he writes. “Lately, this has become a fraught term, associated with elitism and gatekeeping, but I don’t think it necessarily has to be. A true commitment to taste, one that privileges the best writing above all considerations, requires an editor to ignore arbitrary boundaries in the pursuit of new literature.”

The social consciousness and taste of Ross and the editors is on full display in the five hundredth issue, which brings together a range of work, including Kim McLarin’s cutting and emotionally frank piece on attending the criminal sentencing of her nephew, blending reportage with clear-eyed assessments of her own life, and Ben Fountain’s coming-of-age story about a young girl in Dallas, one of his first fiction pieces since publishing his novel Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (Ecco, 2012). Danielle Evans’s story about a young woman caught in the center of Internet-inflamed racial tensions on a college campus is an ingeniously crafted piece that shifts as the protagonist’s history slowly comes into focus. Another story, by Sidik Fofana, follows a woman struggling with her inner convictions while trying to stave off eviction and crackles with energy. The issue also features poems by Donika Kelly, whose debut collection, Bestiary (Graywolf Press, 2016), won the 2015 Cave Canem Prize.

Under Ross’s stewardship, circulation for the review is already back up to more than 1,500. The journal also publishes micro-interviews, book reviews, and blogs on its website, which attracts more than three thousand visitors each month. Going forward the editors hope to continue publishing a wider range of work, including translations, conversations with playwrights and historians, a series of editorials on the state of American letters, and more long-form interviews and craft essays.

Ross is also always searching for new work, and the journal is open to submissions (via the online submission manager) until next summer. “We urge people to subscribe, especially aspiring writers who are perhaps unfamiliar with our publication,” says Ross. “And then please submit your work to us. We’re always on the lookout for new writers and have a great track record of launching new writers’ careers.”

Dana Isokawa is the associate editor of Poets & Writers Magazine.