In our Craft Capsules series, authors reveal the personal and particular ways they approach the art of writing. This is no. 162.

“Distractions can be useful,” writes Carl Phillips in his most recent book of essays, My Trade Is Mystery: Seven Meditations From a Life in Writing, “for pulling us away from self-consciousness about making, and for increasing instead the chances for the seeming accident that, even now, after so many years, each new poem feels like.” Truer words were never written. What would my notebooks, whose scattershot contents have seeded virtually all of my work, even be, if not for the panoply of distractions I’ve let pull me away from respective tasks at hand—and, yes, from self-consciousness about making—over the course of my life as a writer?

Distractions increase the chances for accident, as Phillips says—and accident, I would add, increases the chances for encounters with what I like to think of as “accidental poetry.” Elizabeth Bishop’s extraordinary poem “The Man-Moth,” for instance, would never have come to be, had she not happened upon a particular newspaper typo and, most importantly, had she not recognized the accidental poetry lying latent in the mistake. “I’ve forgotten what it was that was supposed to be ‘mammoth,’” Bishop shared in the essay “On ‘The Man-Moth’” (1962). “But the misprint seemed meant for me. An oracle spoke from the page of the New York Times, kindly explaining New York City to me, at least for a moment.”

So, back to my notebooks’ all-over-the-place and all-generative contents: snippets of poorly dubbed movie dialogue, bizarrely phrased menu items, billboards with missing letters, nail polish color names (the more off-brand, the better); these are the found bits of accidental poetry that have, if not outright inspired, at least played critical roles in untold poems of mine over the years, and untold poems of mine yet to be written.

Ninety-nine-cent stores can often be—I’ve found by chance (how else?)—particularly fertile sources of accidental poetry. Many of the companies responsible for the merchandise arrayed on a discount minimart’s fever-dream shelves are located outside the United States and must not go in for things like professional translators (if they did, how could they sell you that permanent hair dye for only $1?). I would never disparage a person’s efforts to communicate in English—a hegemonic language I have no interest in policing—but I do think it’s worth paying attention to international corporations’ marketing jargon, suspect in any language. And the dry lingo of product descriptions and assembly instructions, transmitted and transformed by the various tongues of global capitalism, can be astonishingly (if unwittingly) poetic.

I will always remember, for example, the school-supplies section of a dollar store in Brooklyn, New York, where, some two-odd decades ago, I came across a translucent sea-lettuce-colored plastic folder with nothing on it but the words, “Do you know the children’s times?” I have yet to decipher the meaning of this somehow ancient-sounding question—much less to find its answer—which is to say: I have yet to write this found-poetry fragment’s long-lost poem. But I will. And then, of course, there was the ninety-nine-cent store in Queens whose toy section presented me with a roughly orbuculum-sized package, which read:

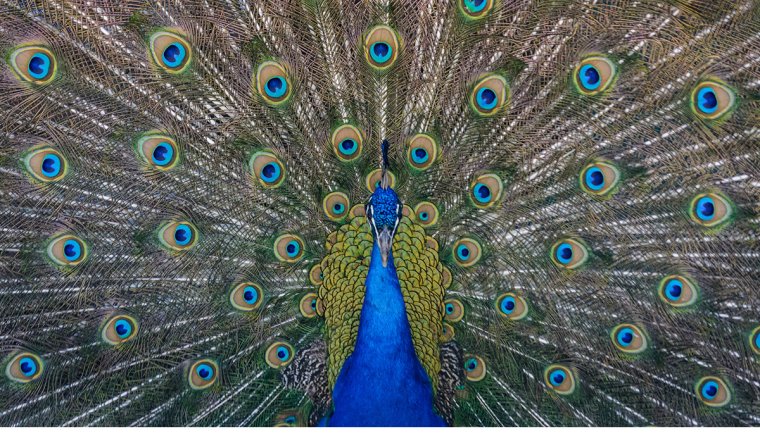

Beautiful Peacock (It will give you Infinite Pleasure!)

FUNCTION:

1. Flashing.

2. It’s Feather Consecutive Flexible.

3. Neck can stagger.

4. Immediately change dir-

ection when hitting obs-

tacles.

This extraordinary and confounding Peacock—who, in its corporeal form, was housed in a box I never bothered to buy (for ninety-nine cents or more), or even to peek inside, during all the years I lived next door to Sunrise 99 Cents or More—for some reason gets outsize attention now as a stalker of my subconscious. It makes several cameo appearances over the course of my long-sequence “Arpeggio Progression in Missing Key,” for instance, the last poem in my book peep (Waywiser, 2022). Here’s one of its particularly Peacock-centric sequences (#7):

on the way to where

we’re going

we talk about missing

things on dry land on dry land

someone had a heavenly

peacock they never took out

of the box the box

said its function was changing

direction immediately when hitting

obstacles

& flashing

the peacock will give you infinite

pleasure its neck can

stagger it is

feather consecutive who knows

if any of that’s true though it was all

according to the box

I recently read Kathy Fagan’s fascinating second book, MOVING & ST RAGE, in the eponymous poem of which Moving and St. Rage “become mythic characters from a failed romance,” as Fagan herself puts it. The ur-source of the book’s profound lyric insights is, of course, a moving-and-storage-company sign with an errant “o” that she’d once rambled past.

“One is offered such oracular statements all the time, but often misses them,” Bishop continues in her brief essay on “The Man-Moth.” You have to be open to the world—to its newspaper misprints, its signs with fallen-off letters, its discount-store products with their curious phrasings—in order to receive its prophecies and poetries. Stop paying the world attention and it’ll slyly palm its offerings, like the Man-Moth himself at the close of Bishop’s eponymous poem:

Then from the lids

one tear, his only possession, like the bee’s sting, slips.

Slyly he palms it, and if you’re not paying attention

he’ll swallow it. However, if you watch, he’ll hand it over,

cool as from underground springs and pure enough to drink.

Danielle Blau’s debut full-length poetry collection, peep, was selected by Vijay Seshadri for the 2021 Anthony Hecht Prize and was published in both the United States and the United Kingdom by Waywiser Press in 2022. Her nonfiction book, Rhyme or Reason: Poets and Philosophers on the Problem of Being Here Now, is forthcoming from W. W. Norton.

Art: Steve Harvey