What a thing, to marry into a family,” Elizabeth McCracken writes in her latest novel, Bowlaway, out this month from Ecco. “What could be more perilous? And yet people did it all the time. They married and had children, every child a portmanteau, a mythical beast, a montage.”

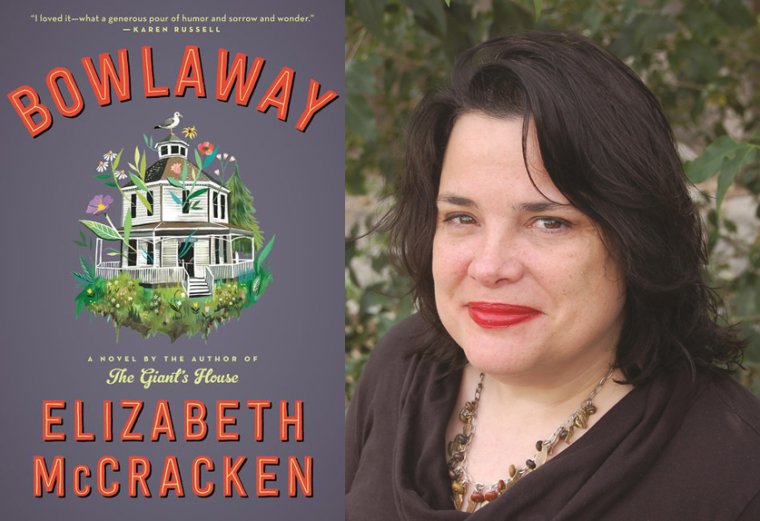

Elizabeth McCracken is the author of six books, including the new novel, Bowlaway, published in February by Ecco. (Credit: Edward Carey)

All families form their own mythologies—and it’s no surprise that McCracken is drawn to this idea, given that her own grandfather was a genealogist. It’s his vocation that gave McCracken the inspiration for her new book, a multigenerational family saga set in the fictional town of Salford, Massachusetts, and centered around a candlepin bowling alley. “I went through genealogies and pulled out names,” McCracken said during a recent phone conversation. “So the first thing I had before I knew anything else was character names. This is completely different from anything else I’ve ever written before. And then the names suggested the people, if that makes sense.” Over the course of 384 pages, readers meet Bertha Truitt, the tenacious owner of the bowling alley with a mysterious past, and her husband, Leviticus Sprague; along with Joe Wear, Nahum Truitt, Cracker Graham, and a complex and compelling cast of other characters borne of both McCracken’s research and her imagination. But none are quite so inimitable as Bertha, a magnetic and enigmatic woman described as “the oddest combination of the future and the past anyone had ever met.” It is Bertha who forms the backbone and the heart of the story, even long after she’s gone.

Anyone familiar with McCracken’s work (or who follows her on Twitter, @elizmccracken) knows that she’s funny. Since her first story collection, Here’s Your Hat What’s Your Hurry, was published by Random House in 1993, McCracken has made a name for herself as a writer who’s able to find the humor in life, however dark it might be. “I feel like books that have absolutely no humor in them can’t actually speak to the human condition,” she says. The author of four previous books of fiction, including The Giant’s House (Dial Press, 1996) and Thunderstruck & Other Stories (Dial Press, 2014), winner of the 2015 Story Prize; as well as a memoir, An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination (Jonathan Cape, 2009), she holds the James A. Michener chair in fiction at the University of Texas in Austin. I spoke to McCracken about her new novel—her first in more than a decade—as well as spontaneous combustion, effigies, humor, family, and the stories we inherit.

What drew you to the topic of candlepin bowling in the first place?

I live in Texas now, and I miss New England. Candlepin bowling is about as New England as it gets. I grew up a couple of blocks away from a bowling alley in Newton Corner, Massachusetts. I was on bowling leagues when I was a kid and it was where video games first came, so I spent a lot of time hanging around it.

Bertha Truitt is such a larger than life, mysterious character whose presence impacts the entire book. I love the fact that she insists on having invented candlepin bowling, and that she meets her husband in the cemetery. There’s something fantastical about her, and at one point you even refer to her as Victorian. Do you come up with your characters or the story first, and how do you shape the characters as you continue to work on a book?

I feel like it was much different for this book than anything I’ve ever written, particularly different from my first two novels, which were both written in the first person. The best metaphor I can come up with is that it’s a little like I found an immense and dirty oil painting in a flea market, and the experience of getting to know the characters had a lot to do with cleaning the canvas. So I knew that Bertha Truitt and Leviticus Sprague were going to be the main characters of the book, and they were surrounded by a lot of characters but not necessarily ones that I could see.

Originally there was a ton more backstory, although it was always kind of mysterious about Bertha Truitt; the first draft actually started in her childhood, and then I realized the book would only work if I focused it around the bowling alley itself.

Have you always known that you wanted to write something that had to do with genealogy, or was this a more recent development?

I always knew that I would get around to it, and I think my first conception of the book was a lot more genealogy obsessed. People in genealogy behave in very orderly ways even if there are strange stories about them; they exist exactly where they did on the family tree and they don’t bust out, but fictional characters are not so docile. So once I started writing and the characters became clearer, I understood: OK, I have to follow them where they go.

I want to talk about the use of mythology in Bowlaway. When Bertha is in labor, you write, “Bertha was part of the house, the house was part of her, they were a mythical domestic creature.” In many ways, this novel addresses the idea of women taking up space, whether it’s laying claim to a bowling alley or a lover. Do feminist origin stories and mythologies inspire you?

There are things that I do consciously and things I do unconsciously when I write. But I’m always aware when I take a step back that whatever is going on in the world is shoved in the front of my head, or maybe in the back of my head, and then it comes out in the writing. Certainly I’ve been thinking about how women take up space in the world. Because it has been a preoccupation of mine as well as the general culture in interesting ways in the past few years, it absolutely worked its way into the book.

The question of myth, it’s interesting because I’m also always interested in the stories that you can’t research. The stories that sort of get lost in time and what gets recorded and what doesn’t, and what rumors get turned into myth. One of the things that was taken out of the book that I had been thinking about when I started it is that there are a lot of entries in genealogies where a woman will be referred to as “probable wife of.” Women can be a big problem for genealogists because they change their names, and recorded history has always been more interested in men. It’s easier to research men because their names and identities in terms of the historical record are much more consistent. I was interested in writing about women who then countered that in some way, as well as women who got caught up, who got lost in the cracks between generations because there is just not as much recorded history.

I’ve noticed that grief comes up again and again in your writing. In Bowlaway, grief even leads to spontaneous combustion. You write: “But we know: grief looks like nothing from the outside, it looks like surrender, but in fact it is the most terrible struggle. It is friction. It is a spiritual grinding, and who’s to say it cannot produce a spark and heat that, given fuel, could burn a good man to the ground?” This particular chapter really fascinated me—the idea of grief literally consuming someone.

Clearly it’s one of my topics, which sounds a little cold-blooded. It’s something that I think I’ve always written about because in a lot of the earliest things I wrote, their origins were in family stories. And I was very close to my mother’s mother, and I was close to my father’s parents as well, and then to a cousin of mine, who was my first cousin twice-removed but she was my grandfather’s first cousin. If you talk to people born in the early twentieth century, you can’t get away from it. In anybody’s family there is always the picture of the lost child or the young husband. I talked to my grandmother and my cousin Elizabeth, and the people who they had lost decades and decades ago they still missed so acutely. They were part of the story of their lives, and I feel like the way that I understand novels is so connected to the way that I understand the stories of my family. The moment I first started thinking about novels I thought about the way that my family or anybody’s family fit together—the things that were in the past that caused people to act differently years and years later. And also I feel like I’ve written about a lot of characters for whom grief is fresh in the past but it hasn’t destroyed them, so I was sort of interested in writing about a character who doesn’t just soldier on. And also, I just always wanted to write about spontaneous combustion.

How important is humor in your work?

Sometimes I write something because I’m delighted to make a joke, but the thing I really believe about writers is that you write the way that you process information about the world. People who are really drawn to plot as the foundation of whatever project they are working on, they do that because they think of the world as being defined by events; and people who are drawn to character first are people who understand that the world is defined by character. I mean joking by the graveside. If I have a religion, it’s that. Every now and then I write something that I think is tremendously serious and somebody will tell me it’s hilarious. It’s impossible for me as a writer to keep a sense of humor and a sense of the absurd out of it. As a reader, I’m generally not interested in reading books that are absolutely devoid of humor. I don’t even mean I need there to be jokes or comic characters, just some sort of sense of the absurdity of the world, something that leavens the world. Every now and then I’ll say to a student—because I talk a lot about humor when I teach—I really do believe that humor amplifies sadness in fiction. And vice versa, sadness makes funny things funnier. And I’ll have a student say to me worriedly, “I think my work is all funny.” And they are always wrong. I’ll say, “You don’t make jokes; your characters understand that the world is absurd or occasionally surreal.”

You’re married to the writer and visual artist Edward Carey. Do you read one another’s work?

Eventually, but not while it’s going on. I think it feels important not to read stuff while it’s going on. So I didn’t tell him what this book was about, I didn’t show it to anybody if anyone asked me about it, until I had a first draft. And I wrote the book faster than my other novels. This one took less time, and I think part of it is because I didn’t show it to Edward and didn’t show it to anybody, and so it felt sort of entirely mine, like I worried less about whether things made sense or were working as I was writing. He was the first person who read it when I was done.

At one point I was trying to figure out a way to keep Bertha in the second part of the book once she had died. One night we were in England for Christmas with his family, and I dreamt about having a sort of effigy for her around, and I started writing it. And then at one point I realized that this effigy was very much based on a wooden woman that Edward had made, his earliest piece of art for his Madame Tussaud book, Little, and she appears in that book. Right now she’s at the Austin Public Library because Edward is having an exhibition, but normally she is in our living room. And she’s traveled. But he made her in 2003, so she’s lived with us for a really long time. So I talked to him about it and I gave him the pages to read, and he said, “Yeah, it’s fine.” So now it’s like an homage as opposed to conscious plagiarism. I had this dream, and it was like, “Oh that’s it, that’s going to solve all the problems.” And I can’t even remember at what point I realized, “Wait a minute…this seems familiar.” I also forgive myself because I lived with her for so long.

She’s part of your consciousness, too.

Yeah, exactly. She’s got my hair, literally, the wooden woman. He made her when we were living in Ireland for a summer, and I had long hair and went and got it cut short so she could have hair. Listen, we share DNA. It feels OK that she worked her way into my book!

Michele Filgate is a contributing editor at Literary Hub and the editor of an anthology, What My Mother and I Don’t Talk About, forthcoming from Simon & Schuster in April. She is currently an MFA student at New York University, where she is the recipient of the Stein Fellowship. Her work has appeared in the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the Boston Globe, Slice, Tin House, Gulf Coast, the Rumpus, and many other publications. She teaches creative nonfiction for the Sackett Street Writers’ Workshop, Catapult, and Stanford Continuing Studies and is the founder of the Red Ink series.