It was an indelible announcement written in black and white for all to see. The first nationally published poem of Gwendolyn Brooks’s appeared in American Childhood, in October 1930, when she was only thirteen years old. Earlier, at eleven, she’d published four poems in a local neighborhood paper, the Hyde Parker, foreshadowing her brilliance. It was a brilliance that would shine through decades and across nations, bedazzling and impacting hundreds of poets and millions of audiences, in all walks of life.

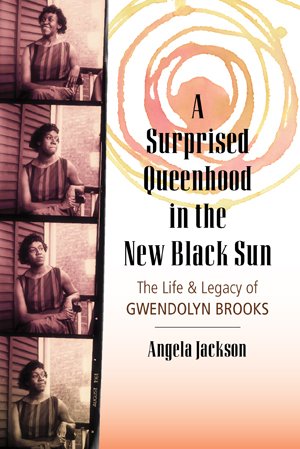

Excerpted from A Surprised Queenhood

in the New Black Sun: The Life & Legacy

of Gwendolyn Brooks by Angela Jackson,

forthcoming from Beacon Press on May

30, 2017. Reprinted with permission

from Beacon Press, 2017.

Gwendolyn was a black teenager living on a quiet street in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood at 4332 South Champlain Avenue, where her family had lived since she was four years old.

Bronzeville, the name coined by an editor of a black newspaper, the Chicago Bee, was named for the color of the area’s inhabitants. In those days, Bronzeville proper stretched from Thirty-First to Thirty-Ninth, and from State Street to Cottage Grove. It was a jewel of colored masses in a segregated space. The people were too often poor and illiterate, but they were also industrious and dignified, creative in music, language, dance, and style. They were the salt of the earth and birds who managed to fly with cramped wings. Gwendolyn, ever observant, settled in to learn the ways of her people, the geography and genius of Afro-America.

Hers was a protected space guarded by father and mother. She and her brother, Raymond, were nurtured and shielded by their father, David Brooks, a janitor at McKinley Music Company, and by their mother, Keziah Wims Brooks, a former schoolteacher who had given up working in the classroom to guide her own children. Gwendolyn was loved.

***

It was 1930 when she made her national debut. The world was just entering the Great Depression. But Gwendolyn didn’t feel depressed. She was buoyed by dark ink on the pages of Writer’s Digest, which she discovered at age thirteen. She reveled in the company of other writing souls who were on the same quest as she—to have their expressions published. She learned to send her work out, to include a self-addressed stamped envelope so that it might be returned when it was rejected. For rejection would and did come. She sent poems and stories out. She got them back. Her desk was her headquarters. But one day the letter she had been waiting for, a letter of acceptance, did come. At that moment, she was deliciously light-headed and light-hearted. Her first poem, “Eventide,” was published in a national magazine. No doubt, her family celebrated her. She basked in her first victory, her announcement to the world.

When the sun sinks behind the mountains,

And the sky is besprinkled with color,

And the neighboring brook is peacefully still,

With a gentle, silent ripple now and then;

When the flowers send forth sweet odors,

And the grass is commonly green,

When the air is tranquilly sweet,

And children flock to their mothers’ sides,

Then worry flees and comfort presides

For all know it is welcoming evening.

Of course, there were no mountains in Chicago—except for the mountains of clouds in the sky a young Gwendolyn was fond of studying. And no brook ran down Champlain Avenue. But Gwendolyn had learned, in her extended reading, about these natural wonders, and her imagination soaked up the solace of nature’s beauty. Her experience in the Brooks household provided the template for the comforts of a “welcoming” home.

She was a pretty girl in her darksome way. And she was in love. She was always in love. Words and books were the love of her young life. Who would have thought that a baby girl born to David and Keziah Brooks in the dining room of her grandparents’ two-story, single-family home at 1311 North Kansas Avenue in Topeka, Kansas, on June 7, 1917, would so soon become a published poet? Her parents, having migrated to Chicago earlier, had returned to Topeka for her birth. Gwendolyn was born during the Great War across the ocean, but she must have felt the reverberations of a world in conflict as she grew up. Negro soldiers were deemed unfit to fight by US commanders, so they battled under a French flag and returned home as heroes. She would become used to the theme of war. She was in touch with it, even in her little corner of the world.

Gwendolyn wrote poems a long time before she was published. She would sit on the top of the back steps and dream in poetry about the magic of sky and the mysteries of her future. She wrote a poem a day from the time she was eleven. Sometimes two or three. She was devoted to her poetry because her mother believed in her ability, her gift for it. When she was seven, she showed her mother her page of rhymes. Her mother was overjoyed, excited at the possibility of a poetic daughter who would conquer the segregated world with elegant and eloquent language. She, a schoolteacher, knew how important it was to achieve in letters.

“You’re going to be the lady Paul Laurence Dunbar!” Keziah Wims Brooks exclaimed. And Gwendolyn believed this because her mother had said it was so. Her mother would do all that she could to make it happen. For example, early on Gwendolyn did not have to do chores. Then later she dusted, swept, did some laundry, and washed dishes. But her mother carried the work of the household. Her mother sang “Brighten the Corner Where You Are” as she went about her work for her gifted child. Gwendolyn, with pen in hand, brightened her own corner in her little room of her own.

When she was in her early teens, her father gave her a desk of her own that he got from McKinley’s. It was a desk full of compartments where she kept notebooks that she’d been writing in since she was eleven and special books like “the Emily books,” L. M. Montgomery’s books about a Canadian girl who, like Gwendolyn, wanted to be a writer. Of course, she kept The Complete Paul Laurence Dunbar.

When Gwendolyn wasn’t writing, she was reading. Even at Christmas, she read. She sat near the Christmas tree and re-read the same book on that holy day: The Cherry Orchard, by Marie Battelle Schilling, a gift from Kayola Moore, her Sunday school teacher at Carter Temple Colored Methodist Episcopal Church. Gwendolyn would sit amid tinsel and gold, under a star-topped tree, and lose herself in the same book each year. Or did she find herself in the same book? Did she find herself in any story or poem—a vibrant, vivid, adventuresome self who taught her to live more confidently, at least in her mind? She only had a few friends on her short block.

She was a dark-skinned girl at the time when being a decidedly dark girl was not the most desirable thing to be. Black people, worldly-wise, sang, “If you’re white / You’re all right. If you’re yellow / You’re mellow. If you’re brown / Stick around. If you’re black / Get back. Get back. Get back.” Gwendolyn understood the color code. She was bright that way. At the time her first poem was chosen for publication, she was not the most popular girl in any part of Negro society. But her self-esteem did not depend on others choosing her. She chose herself. Rejection hurt, but she had early on fallen in love with her own color because her parents, by their love of her and her brother, had taught her to love the totality of herself.

On her block, Gwendolyn was known. Even if she spent most of her time in the house, in her room at her desk, writing poems and stories and reading sometimes two books a day, she belonged. At school it was a different matter.

When she went to grammar school, to Forrestville Elementary School, outside her immediate neighborhood, she encountered teasing every other day about her complexion. Her classmates called her “Ole’ Black Gal.” At the time, most of the kids believed everything black was bad—a black heart, a black mood, a black knight, a dark design.

In describing herself as she was in her early teens, she said she was “timid to the point of terror, silent, primly dressed, AND DARK. The boys did not mind telling me that this was the failing of failings.” Gwendolyn withstood the insults but noticed the reverence her classmates had for the light-skinned girls.

The boys were drawn to light-skinned girls like magnets. They fawned over Rose Hurd, Eleanor Griffin, Rebecca Dorsey, and Gwendolyn’s friend Ida Briscoe. These girls had boyfriends. Gwendolyn did not garner the attention of young Negro males until later, when she conversed with Joseph Quinn, light-skinned Herman Lawrence, Theries Lindsey, and more seriously dated one Kenyon Reid. She had the consolation of and preference for books and her own creative impulse. Because of her interests and temperament—and especially her color—she did not fit in at Forrestville Elementary School. She learned that lightness was one crucial way that Negro society established the worth of its members.

The length and texture of the hair was also important to popularity. It had to be long and curly, and it was best if it did not need a hot comb to be straight or free from kinks. That was Good Hair. Gwendolyn did not have Good Hair. The wardrobe had to be fine, as well, reflecting the economic station of the parents—professional men like lawyers, doctors, politicians or porters and postal workers. To have a schoolteacher for a mother was a boon. But Gwendolyn’s mother was retired, and the family did not have the extra income anymore.

To top it all off, Gwendolyn was not athletic. She did not tumble and jump with ease. She had few social graces. She did not know how to make witty repartee and coin new phrases. Her classmates kept up the insults. One of Gwendolyn’s earliest extant poems seems to be a response to personal slights and insults.

Forgive and Forget

If others neglect you,

Forget; do not sigh,

For, after all, they’ll select you,

In times by and by,

If their taunts cut and hurt you,

They are sure to regret

And, if in time, they desert you,

Forgive and forget.

Gwendolyn’s answer to the cruelty and insensitivity of young schoolmates was the perfect response she learned in the Sunday school she attended every week—a Christian, turn-the-other-cheek answer, reflecting a belief that things would be right by and by. It was a deeply held belief among African Americans as well. This belief, in Gwendolyn’s mind, extended to whites, as well. She was working her life out in the privacy of her poetry.

Think of the pain of a sensitive black girl, beloved at home and snubbed at school, taunted in this way, at best ignored, at worst maligned. The hurt of it ran like a central seam in the garment of her writing. It would later inform her worldview and hold it together.

But as a student, she searched for a place to fit her dark self. She went to three different high schools in this effort.

Her first was the predominantly white Hyde Park Branch, at 6220 South Stony Island, where it was said the best students went. Gwendolyn hated her experience there, though. She felt isolated because she was isolated. She was a black canoe in a sea of whiteness. She was ignored, invisible to all but a few white boys, she would say later, who took an unreciprocated liking to her. Was she interesting to them because she was dark skinned and seemed exotic? Was her black skin alluring as forbidden fruit?

Gwendolyn packed up her books and headed to the all-black Wendell Phillips Academy on 244 East Pershing Road, at Thirty-Ninth Street, not too far from her home. She was hungry for a learning experience among her own people. A girl who lived next door to her on Forty-Third and Champlain had sworn up and down that Gwendolyn would “have a ball” at Wendell Phillips with its rich, black social life. But she didn’t have a ball. She wasn’t a have-a-ball person who knew the latest dances, partied on the weekends, played Post Office and Kiss the Pilla. She wasn’t fast, athletic, stylishly dressed, or light skinned with long hair.

The last high school, from which she graduated, was Englewood High School, at 6201 South Stewart Street. Because she didn’t live within the school’s district, she used the address of one of her few friends in order to attend. Englewood was not solidly white like Hyde Park or wholly black like Wendell Phillips. It was mixed, though the majority of the students were white. But she did not feel so much like an outsider there. Still, no one ever said, “Hey, Gwen, are you coming to the party tomorrow night?”

No one ever said, “Girl, didn’t we have a ball last Saturday night!”

Certainly no one ever said, “Oh, you’re a doll!”

Or, “Heaven must be missing an angel.”

But something romantic happened at Englewood, all the same. It was said that “when a white boy of affluent family flirted with her in class, he was threatened by a black boy who had a hitherto-controlled ‘crush’ on her.” What did Gwendolyn make of that scene? She blushed, no doubt mortified.

At Englewood High School three teachers recognized her talent for poetry and writing in general. Ethel Hurn in history and Margaret Harris in journalism encouraged her directly, and Horace Williston in American poetry encouraged her as well. Gwendolyn had tried to be published in the school paper but was rejected; then she turned in a book review—written in verse—of Janice Meredith, by Paul Leicester Ford, which Gwendolyn had only half read because she hated it so. Hurn was greatly impressed with her writing and said Gwendolyn “had a future.” Gwendolyn earned an A and her teacher’s continued interest.

Concurrently, she joined the journalism club, and teacher Margaret Harris also believed in her. She had run into her on the bus one day and told Gwendolyn she thought she had talent. Gwendolyn was embarrassed to be singled out in public on the bus. But at home, in the safety of her room, she reveled in the encouragement. From Miss Harris in the journalism club she learned the W’s—who, what, when, where, why. She also developed a discerning eye, which would help shape her life’s work.

So three white teachers offered her plums of encouragement. There was no black teacher at the school, but Gwendolyn read about the ideas of other African Americans in the Chicago Defender. It was the most popular newspaper about Negro life at the time, and the most respected. An honored guest in many black homes, in truth, it had prompted many African Americans to vacate the cruelties and limitations of the South and seek out the opportunities and promise of the cities of the North.

Founded in 1905 by Robert Abbott and situated at Twenty-Fourth and Michigan Avenue, the Defender was sold by Pullman porters at stop-off points in towns, cities, and hamlets throughout the South. It was the town crier of the national black community and kept black people everywhere in touch with the black condition. It raised a hue and cry about the lynching in the South, reporting in great detail. It highlighted job openings in factories and steel mills in the North, and recruited workers for those jobs. It offered visions of life in domestic service and career advancement for the educated.

In addition, the Defender offered details of Negro social life—weddings, funerals, engagements, graduations, parties, recitals, musical venues, and athletic competitions. Charitable organizations, fraternities, sororities, and social clubs were highlighted. It was the Chicago Defender’s David Kellum who founded the Bud Billikin Back to School Parade, an institution on Chicago’s South Side that attracts hundreds of thousands onlookers and participants from across the city today.

Gwendolyn aspired to publish poetry in the pages of the Chicago Defender. She wanted to publish there as Langston Hughes did. On August 18, 1934, when Gwendolyn was seventeen, the following poem appeared in the pages of this national organ:

To the Hinderer

Oh, who shall force the brave and brilliant down?

There’s no descent for him who treads the stars.

What else shall he care for mortal hate or frown?

He shall not care. His bright soul knows no bars.

Take his weak frame and twist it to your will.

Strive to discourage and to make him fall;

Oh, make him suffer! Cause his tears! But still

Shall not his spirit rise and vanquish all?

What things the Power buried in the skies

Of man’s attempt to bruise and hinder man?

What pity has that Force for our poor cries

When crude destruction is our foremost plan.

Was “To the Hinderer” a hidden response to the chilly racism she’d encountered at Hyde Park Branch School, or a response to editors who were cold to her submissions she’d begun to send out? Or did the poem address, in its velvet-wrapped way, the society at large, surrounding Bronzeville and inside Bronzeville? Gwendolyn’s was a gifted mind answering back with subtlety.

She would continue to send poetry to the Chicago Defender, which published her writings on the uselessness of fame, the bliss of friendship, quarrels. These were mature considerations for an adolescent girl. In four years, she published seventy-five poems in the paper’s Lights and Shadows column.