Ron Currie Jr. was born and raised in Waterville, Maine. His first book, God Is Dead (Viking, 2007), won the Young Lions Fiction Award from the New York Public Library and the Addison M. Metcalf Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. His novel Everything Matters! (Viking, 2009) was translated into a dozen languages and was an Indie Next pick and Amazon Best selection, as well as a best book of the year selection by the Los Angeles Times and National Public Radio. His short fiction has appeared in many magazines and anthologies, including Alaska Quarterly Review, the Sun, Ninth Letter, Swink, the Southeast Review, Glimmer Train Stories, Willow Springs, the Cincinnati Review, Harpur Palate, and New Sudden Fiction(Norton, 2007). A new book will be published in early 2013.

![]()

“Maine is as dead, intellectually, as Abyssinia. Nothing is ever heard from it.” That’s H. L. Mencken, everyone’s favorite curmudgeon-slash-frustrated idealist. He leveled this charge at my home state back in 1925, but his assertion, no matter how dated, raises some legitimate and compelling questions for those of us who hail from north of the Pine Tree Curtain: Are we really a bunch of intellectually irrelevant hicks, the sorry occupants of a flyover state that no one actually flies over? Are we doomed to only ever have contributed two things to the larger culture, one of those things being a good portion of all the toilet paper manufactured in the United States during the twentieth century? (I’ll let you guess what the other thing is, but here’s a hint: It comes in hard- and soft-shell varieties, and once more, for the cheap seats, it’s not actually red until you cook the damn thing.) Also, perhaps most pressingly: What the hell is Abyssinia?

I’m a native-born Mainer with middling intelligence who never progressed past high school. Despite these handicaps, I managed to (a) write a couple of books, and (b) actually convince someone to publish them, so on the surface of things it would seem that I, among many others, prove Mencken wrong in his assertion. But there are caveats here, among them the manner in which I became familiar with the Mencken quote in the first place. I encountered the line not while engaged in deep, independent study of the great cultural critic, but rather while on the toilet. It was in one of those myriad little compendiums that are actually published with bathroom reading in mind. This one was called The Portable Curmudgeon, and it belonged to my roommate at the time, the only friend I have who’s actually grumpier than I am. So: when Poets & Writers Magazine approached me about writing a guide to literary Portland, the first thing that came to mind, the fulcrum around which I decided to let my essay spin, was a bit of intellectual effluvium that I’d memorized, years ago, in the can.

When I first read this line, I worried quite intensely that Mencken was correct about Maine, in large part. Certainly it seemed he was correct about the area of Maine where I grew up and still have an apartment—the central interior, north of the iconic coast and south of the endless woods and great potato fields, a geographic and cultural orphan of sorts. As with most things, of course, how one defines it can depend almost entirely on how generous one is feeling. Either it’s a quiet place full of unassuming people who raise nice families and keep to themselves and leave their doors unlocked at night, or it’s a back-facing hinterland, a series of map coordinates that young, smart people leave for more intellectually and financially rewarding environs pretty much the moment they’re able to.

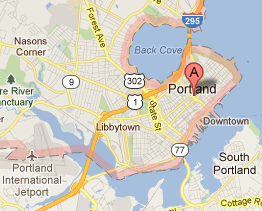

When those young, smart people abandon ship, though, these days they’re a little less likely to go to Boston or New York City and instead travel only an hour or two south on I-95, to where the oasis of Portland can be found. And with good reason. Contemporary Portland is a shining example of what can happen when a community refuses to succumb to the relentless forces of sprawl (represented here by the Maine Mall, which tried to kill Portland’s downtown back in the seventies). With a population of only sixty-five thousand people, Portland nevertheless enjoys the cultural, artistic, and culinary vibrancy of a much larger city. It’s a great place to read, write, talk, listen, eat, drink, loaf, and make loveable old Mencken do a few pirouettes in his grave.

I often write outside the house, and on those days, before settling down to work, I pop into Longfellow Books (One Monument Square), located in the Arts District. The store’s tagline boasts that it’s a “fiercely independent community bookstore,” and that’s not just lip service. (Word to the wise: don’t use your Amazon Visa card at the register if you’d like your viscera to stay where it is). Like all truly great local bookstores, Longfellow is about love, respect, and reverence for printed matter. That may sound obvious, but consider: You won’t find a section full of plush toy animals, they don’t sell CDs or washing machines or hysterectomies or whatever else you can get at online “bookstores” these days, and no quarter has been given to overstuffed furniture for lounging about—all available space is dedicated to bound paper, so if you’re in the mood for a chat, be prepared to do it on your feet. No idea what you want to read? Don’t worry. Someone on the staff knows better than you do, and will literally put a book in your hands and push you toward the checkout counter before you have a chance to protest that you can’t afford hardcovers. This has happened to me on several occasions, and I made the acquaintance of one of my new favorite authors in this manner just a couple of months ago (thanks, Bill!). Longfellow is also deeply connected to the community on multiple fronts, hosting four separate book clubs; sponsoring, in conjunction with Portland Stage Company, Longfellow’s Shorts, a dramatic reading series; and supporting the work of Maine writers in that most old-fashioned and meaningful of ways: by relentlessly flogging their books to everyone who walks through the door. And above and besides all that, the crew at Longfellow does one thing that guarantees the undying loyalty of both authors and readers alike—they consistently put on great readings. There are plenty of seats, once the staff push some shelves out of the way. Smart event planners know to ply their guests with something or other, and at Longfellow this means that there’s always a steady supply of booze on hand. (There has also been talk of an occasion when medical-grade marijuana was passed around before anyone knew what was going on, and by the time they figured it out no one cared about the potential legal consequences). They even have regular customers who bring baked goods to every reading, for God’s sake. They make authors feel like rock stars, and give customers a chance to meet their favorite writers. They are, in short, princes of independent enterprise.

Longfellow is the undisputed heavyweight champion of Portland bookstores, but there are certainly others more than worth mentioning: Carlson & Turner (241 Congress Street), on MunjoyHill in my neighborhood, is a classic antiquarian seller—dark and inviting and slightly musty, with packed shelves that overflow into teetering stacks on chairs and, occasionally, the floor. The staff also practices the fading art of bookbinding and repair. At the other end of the literary spectrum is Casablanca Comics (151 Middle Street) in the Old Port, where they’ve been fulfilling fan boys’ needs for graphic novels and assorted geek gear for twenty-five years.

When I leave Longfellow, usually with some sort of inspiration tucked under my arm, I’ve got several choices about where to settle down for work. Some days I’ll walk through Monument Square, where hipsters and sensibly dressed business types mingle, smoke, and eat their lunches, and cross Congress Street to the newly renovated Portland Public Library (5 Monument Square), which anchors the east end of the vibrant Arts District. I was lucky enough, a couple of years ago—as part of the library’s Cooks for Books program, in which civilians host writers at private dinner parties around the city and their guests cut checks to the library for the privilege of having dinner with an author—to get an early glimpse of the building’s interior before it reopened. It’s a vision of how libraries can adjust their functions and continue to enjoy relevance in a time when most of us have more information available on our smart phones than could ever be housed in a single building. Working with a small budget for such a renovation, the planners avoided major structural changes and instead emphasized simple lines, dazzling use of natural light, and a modern, inclusive feel. Usually I’ll settle down at one of the tables in the atrium, a gorgeous glass enclosure with high ceilings, exposed supports, and lively, distracting views of the activity in Monument Square. A half-level up from the atrium café, but with the same views and warm light, is the periodicals section, which I favor for the comfortable leather furniture (and the equally comfortable way that furniture’s been arranged, so that even when sitting close by or facing other people, one still has the semiprivacy and ownership of space necessary to be alone together, a critical state of mind for getting work done). I’m a restless scribbler, often rising from my chair and moving around to work out a problem or massage a sentence in my head for a bit, and this is where the Portland Public Library really excels (as opposed to, say, a coffee shop, where getting up for no discernible reason every three minutes tends not to endear one to the other patrons, who just want to drink their espressos without having to worry about some potentially unstable person bumping their table as he paces and mutters to himself). The layout of the library—wide open, well lit—invites wandering, and I can even find a semiprivate nook to knock out twenty quick pushups without seeming like exactly the sort of weirdo that I am. If I’m feeling contemplative (or lazy, or otherwise vexed or stymied by my work), I may stroll through the entrance hall north of the atrium and go downstairs into the new Lewis Gallery. I don’t know why, but something about clean white walls hung with modern art is like soma for me. I’m not a huge fan of visual media, and I don’t even have to look at the artwork—just walking through the space is like taking a pipe cleaner to my brain. One lap through and I’m ready to work some more, but it’s worth lingering, too, especially if you’re less the Philistine that I am and can actually appreciate the many merits of visual art that I’m always hearing about. The library also sponsors one of Portland’s better reading series, the Brown Bag Lectures. Remember all those people on their lunch hours just outside in the square? Yeah, the library noticed them, too, and smartly decided to offer a biweekly dollop of literary programming to bring them inside when otherwise they’d just sit there nibbling bread crust and watching the grass grow.

One can’t spend all day every day at the library, though, and when it’s time to move on I’ll usually end up at one of Portland’s ubiquitous coffee shops. Understand, for years I loathed everything about coffee. I hated the way it tastes. I hated the squashed-skunk-on-summer-highway smell it produces when brewing, which always brought to mind DeLillo’s Airborne Toxic Event. I hated people who fetishized the stuff and hatred made it hard to spend any time in coffee shops. I’ve since gotten over myself, though, at least where coffee is concerned. My most frequent haunt is Arabica at 2 Free Street, down toward the water. A funky corner space with brick interior, exposed ductwork, and floor-to-ceiling windows that look out on the Free Street traffic, Arabica is one of those places that always seems busy yet never lacks an empty chair for a writer in search of a workspace. The idiosyncrasy that sets Arabica apart from other java joints is its emphasis on toast. It’s right there on a small, handwritten sign taped to the register: WE SELL TOAST. AN ORDER IS TWO SLICES, BUTTERED. EXTRAS ARE EXTRA. (Personally, I appreciate ordering directions as succinct and forthright as this. I’ve wasted too many minutes of my life staring up at incomprehensible menu boards, trying to force myself, against every instinct I possess, to tell someone I want a “tall” something or other when I know damn well what I mean, and what I’ll get, is a “small” something or other). If you’re skeptical about what can be done with toast to make it something more than, well, toast, just try it. Scorched bread aside, Arabica has a nearly perfect atmosphere for writing, assuming you’re the type of writer who can work with other people around. The furniture’s comfortable, the music is invariably at the ideal volume to be present but unobtrusive, and the staff never give off that unmistakable hit-the-road-malingerer vibe, even if you’ve been nursing a mug of Earl Grey for three hours. Wear flannel and/or chamois, along with a scraggly beard in winter, and no one will ever suspect you’re an author masquerading as a civilian. This holds true at Portland’s other best coffee shops, where I also can be found, though not as frequently. Bard Coffee (185 Middle Street), just around the corner from Arabica, takes its coffee more seriously than any other place in town. To give you an idea of how good Bard’s coffee is: I met Arthur Golden recently, about two thousand miles away from Portland, and we didn’t talk about books, or geishas, or anything as much as how much he adored Bard’s coffee. They use one of those inverted plastic cones to brew by the cup, and for those who are into coffee porn, you can stand and watch and salivate in sweet anticipation while hot bean water drips down into your mug. Then you can fight for a seat (this is my only complaint about Bard; it always seems to be crowded) while trying not to spill any of the black gold. The other shop, with a couple of locations, is Coffee By Design (67 India Street). I go to their India Street storefront, in part because it’s near where I sleep, and in part because a Facebook friend who’s a fan of my books works there, and I keep hoping he’ll recognize me and make a big deal about what a literary celebrity I am in front of the other patrons.

Notice that all the places I’m writing about are local, nonfranchise establishments. This isn’t because I’m trying to avoid including corporate businesses. It’s because in downtown Portland, they’re almost unheard of. As I mentioned earlier, the populace here is genuinely dedicated to the notion of local, independent, and sustainable, and by and large they vote with their dollars without being too sanctimonious or otherwise “Portlandia” about it.

All that caffeine and ruminative stillness means that it’s now time to go for a good, long walk, an activity that Portland is ideally suited for. There are a couple of literary-type spots well within comfortable walking distance of Arabica, the most obvious of which is the Wadsworth-Longfellow House (489 Congress Street). If you know anything about H. W. Longfellow, you knew I’d get around to mentioning him sooner or later. Of course Longfellow was writing before Mencken was a glimmer in his daddy’s eye, and he was born and raised right here. The house has been restored with ridiculous attention to detail—word has it that among other things, laboratory analysis of paint was involved—and now stands as the only single-family dwelling to survive downtown Congress Street’s transformation from a residential neighborhood to the business district that employs all those sensibly dressed people eating lunch in Monument Square. The real draw for me, though, is the Longfellow Garden, a long, narrow strip of green that gives one the sense of having discovered a beautiful verdant secret among the endlessly abutting brick-and-concrete in this part of town. There’s a lilac here that goes all the way back to the turn of the twentieth century, when Longfellow’s younger sister Anne gave the property to the Maine Historical Society. For me, looking at a hundred-year-old flower in full bloom offers the kind of perspective that is difficult to find elsewhere.

If I don’t feel like I’m quite finished contemplating my meager place in American letters, I might head west a few blocks on Congress Street to Longfellow Square, where a statue of the man rests in the middle of the crazy intersection built to accommodate it. Traffic reroutes for poetry gods, not the other way around. The great man sits, magisterially bearded, in a simple chair; a funny and slightly perplexing aspect of the monument is that he seems to be wearing an overcoat, despite the fact that one presumes the chair would’ve been indoors. People have fun dressing Longfellow up for the seasons, including Christmas, when he usually wears a festive scarf and has a present resting in his lap. As a side note, if you’re into raw fish it’s worth walking across from the Monument to lunch at King of the Roll (675 Congress Street), where the chef is a Japanese man with the unlikely handle of John Wayne.

A bit farther out toward Portland’s west end (I wouldn’t recommend trying to walk this, though, unless you’re feeling ambitious) one can find the campus of the University of Southern Maine, home to the storied Stone Coast writing program, as well as the Maine Festival of the Book. The festival, which in the past struggled mightily against funding and venue problems, has more recently taken full bloom, and this year offers a staggering number and variety of events over three days, March 29 to April 1, including an opening night party that features many of the presenting authors, as well as a lecture by Pulitzer Prize–winner Tony Horwitz.

Doubling back in the direction of my neighborhood, I hang a right toward the water and end up on Commercial Street, the busy main throughway of Portland’s Old Port district. As is the custom everywhere in Maine, some locals bristle at places that draw lots of people from far away. They consider the area annoyingly tourist ridden and kitschy, which it can be, especially during the summer. But that sort of provincial grumpiness, when it comes to Commercial Street, misses the point. Certainly there are plenty of tourist traps selling schlock, and in high season you have to stop your car every three feet to let a group of cruise boaters cross, but there’s also a panoply of good restaurants, bakeries, and pubs, including at least one with a window sign that forbids bikers from wearing their colors inside. You can buy an uber-expensive custom blazer, then walk a hundred yards and give your labradoodle a spit shine at a self-serve dog wash. Perhaps most important, Portland has taken pains to ensure that this remains an actual working waterfront—tourism hasn’t replaced or displaced the fishing industry, as it has in so many other coastal communities, and you’re likely to find lobstermen drinking on stools right next to sunburned Carnival patrons in floral-print shorts and goofy sandals. Commercial Street is also the home of the Telling Room (225 Commercial Street), Portland’s answer to 826 Valencia, where students learn to write their stories their way and are treated as working artists. The nonprofit writing center was founded in 2004, and in addition to the workshops and summer camps on offer for young writers, it also sponsors the Super Famous Writers Series, which has brought Dave Eggers, Jonathan Lethem, Susan Orlean, George Saunders, and others to Portland. What’s more, the staff loves having guests. So stop by, sit in on a workshop, offer to help.

A bit down the road from the Telling Room, just off Commercial Street, is the legendary J’s Oyster (5 Portland Pier). It’s not a great place to write—it’s a shack on the wharf, really, where even those of average height feel they have to duck on entering, and it’s always busy and loud in an exceedingly friendly way that makes it hard to think but easy to smile—yet it is a great place for an afternoon pint and steamed clams. You can’t get fresher mollusks anywhere; the boats they came off of are bobbing on swells within view of J’s large harbor windows. J’s is how Maine does an oyster house. The menu is brief and no-nonsense (special orders do upset them, so don’t bother asking), both the help and the clientele are nice but not overbearing, and the sun is always officially over the yardarm, no matter what the clock says. What’s more, J’s is people watching at its best, and since writing is in large part microanthropology, I consider an afternoon at J’s to be work, even if I do it with a beer in hand.

Eventually I’ll stagger out of J’s, intent on clearing my head with a smoke and a long walk up Fore Street to the Eastern Promenade. Seventy acres of gently sloping grass that overlooks Casco Bay, the Eastern Prom in warmer months is an ideal place to read and write, and though understandably popular with the locals, it’s big enough that one’s never bumping elbows. Benches and picnic tables abound, but most people keep it real and just bring blankets to lie on while they take in the view of coastal islands and the B&M Baked Bean factory. (That’s right: If since 1867 you’ve ever eaten a can of B&M baked beans, they were made right here). You can watch ferries, sailboats, and trawlers creep across the bay, and if you’re the type who gets out of bed early, the sunrises here are among the best anywhere in the country. I’ve solved more than a handful of narrative conundrums while sitting on the Prom, and also saw the biggest banana slug in Maine history while walking there to take in the sunrise after a long night of drinking.

Eventually the Prom meets with the eastern terminus of Congress Street, and if I turn there and head back toward the Old Port I can stop halfway down Munjoy Hill at Mama’s Crow Bar (189 Congress Street), where the official motto is: “Beer, Friends, Music, Prose.” The unofficial, but equally important motto is: beer only, cash only. Mama’s is a tiny place with barrel tables and a house chihuahua, but if you get there on the early side it’s easy enough to find a good spot at the bar to scribble while drinking a tall boy. In addition to both scheduled and impromptu music, Mama’s hosts the Scratchpad Reading Series, a lively and fun event that’s been going on since 2010 and has settled into a more-or-less quarterly schedule.

By now it’s probably getting late in the day, and with evening coming on that usually means something interesting and artful is happening at SPACE Gallery (538 Congress Street), at the opposite end of the Arts District from the public library. SPACE is a multidisciplinary performance and exhibition undertaking. It’s where I first witnessed full-frontal nudity in a play (twice in the same play, actually, and in an admirable nod to gender equality both man and woman parts were on display) and where I heard a reporter give a heart-stopping talk about a deadly mortar attack on an Army base in Iraq. Varied as the programming is here—one night you can see a multimedia lecture on the history of porn (from someone who knows his subject firsthand, ahem), and the next sit down for a documentary about A Tribe Called Quest—there’s plenty of purely literary things going on too. A regular SPACE series called Slant (which takes its name from an Emily Dickinson quote: “Tell all the truth but tell it slant”) presents ten-minute stories from a select group of writers and performers—no props, no notes, just words. And in keeping with SPACE’s stated mission of bringing the best national and international artists to Portland, they’ve brought in authors—such as Steve Almond, who recently conducted two workshops during the day and a reading with discussion in the evening—from all over. Did I mention there’s a bar, too?

And speaking of bars, the events at SPACE usually let out around the nine to ten o’clock range, a good hour to begin in earnest that favorite pastime of writers across the ages: the consumption of fermented sugar for the purpose of making other people more interesting. Like any coastal town worth its salt, especially one where you can reliably expect winter to last five solid months, Portland has an abundance of good to great drinking establishments—far too many to enumerate here. There are plenty of twelve-dollar-a-drink mixology joints and lunkhead pubs where the dress code is strictly backward baseball cap, but if you find yourself having a late-stage Bukowski kind of night, as I sometimes do, there’s only one place to go: Sangillo’s Tavern (18 Hampshire Street), tucked away at the Old Port’s outer edge, like a grimy kid in timeout. The barroom is cramped and badly in need of fresh paint, there’s a house Yahtzee board, and just inside the entryway is the only functioning cigarette dispenser I’ve seen in years (come to think of it, I’m pretty sure Maine outlawed those things a while back, yet there it is). Naturally there’s a trick to convincing the cigarette machine to actually give you cigarettes—I spent a good five minutes in drunken vain pulling on the knob that was supposed to avail me a pack of Marlboros before a regular came by and Fonzied the relic, leaving me slightly chagrined but nonetheless satisfied nicotinewise. Sangillo’s is the place your local dive bar wants to be, but can’t, because it has neither the pedigree nor the all-star roster. If Dylan Thomas had lived in Portland, he would have died at Sangillo’s. I once spent the better part of a beer trying to figure out which song an incomprehensible old drunk wanted me to play for him on the jukebox. I had a long and random (do I need to keep mentioning “drunken?”) conversation with a woman who works a cafeteria car for Amtrak—we’d chatted on the train once while I was buying a sandwich, and somehow, months later and through an alcohol-induced haze, she not only recognized me but also remembered I was a writer. At Sangillo’s, mixers are an afterthought, the bartenders call you “Hun,” and there are usually free Jell-O shots for those who tip well. Mencken, no doubt, would have hated it. But much as I’d like to, there’s no way I can stay until closing—after all, I’ve got to get up tomorrow and dispel the persistent notion that Maine is intellectually DOA, and drinking rotgut until 2 AM probably won’t help.

Editor’s Note: Sangillo’s Tavern has closed its doors. The owner of Sangillo's has opened Tomaso's Canteen in the same location.