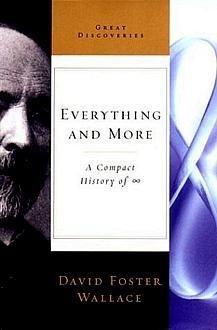

David Foster Wallace’s long-awaited sixth book will arrive in bookstores next month. But it’s not what some might expect from the author of Infinite Jest (Little, Brown & Co., 1996) and A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again (Little, Brown & Co., 1997).

Wallace is one of several literary writers contributing to a series of nonfiction books about scientific breakthroughs called Great Discoveries, published by W.W. Norton and Atlas Books. The first two books, to be published next month, are Everything and More by Wallace and The Doctors’ Plague by Sherwin Nuland, clinical professor of surgery at the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, and the author of the memoir Lost in America: A Journey With My Father (Knopf, 2003).

Wallace explores the concept of infinity and the 19th-century mathematician Georg Cantor’s definition of it, while Nuland tells the story of Ignac Semmelweis, a physician in 19th-century Vienna who introduced the notion that doctors must wash their hands before examining patients.

The idea behind the series is to present science through literary narrative, with a focus on the stories behind science’s greatest discoveries—and the intriguing personalities of the individuals who made them. Over half of the 10 authors of forthcoming books in the series are literary writers, including novelists Madison Smartt Bell, who will write about Antoine Lavoisier and the origins of modern chemistry; Rebecca Goldstein, who will write about the Czech-born mathematician Kurt Gödel; and David Leavitt, who will write about Alan Turing and computer science.

Nuland, who has been teaching medical history since the 1960s, says focusing on the narrative structure of scientific discoveries can make the complicated subjects—radioactivity, the theory of relativity, the atom—exciting. “It’s like putting raisins in cereal to make it sweeter,” he says. “It takes a lot of academic boringness to take out those raisins.”

According to Ed Barber, senior editor at Norton, Great Discoveries offers something sweet not only to readers who enjoy science books, but also to those who wouldn’t normally read a book on science but may do so because their favorite writer wrote it. “David Foster Wallace, for example, has a real following, so this book will be embraced by his fans,” he says. Wallace “can write compellingly about pretty much anything.”

While the list of fiction writers exploring scientific topics adds a level of distinction to the new series, writing about science for a general audience isn’t a new concept. Barber says that in the 1970s trade publishing opened up to science writing, with writers like Stephen Jay Gould and James Watson publishing widely popular books. Jesse Cohen, an editor at Atlas who conceived the idea of having literary writers contribute to the series, agrees. He cites Watson’s 1968 book Double Helix, which presented genetics to a general readership, as an important step in that transformation. “People read it and realized that scientists aren’t these soulless people in white lab coats,” he says. “Science suddenly became exciting.”

Cohen has also been the editor of the annual anthology The Best American Science Writing (Ecco Press) since 2000, and says that in recent years science writing has become increasingly popular—with literary as well as academic writers. “We’re at a point where literary writers aren’t only interested in appropriating science into their work—science itself has become their work,” he says. “Of course, science can’t tell us everything, but it can tell us a little about who we are and where we come from.”

Dalia Sofer is a freelance writer who lives in New York City.