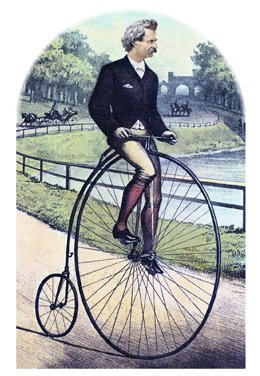

This appears to be a fact: Some time in the early 1880s, when he was approaching his fiftieth year, Mark Twain set out to learn how to ride a bicycle, a big-wheeled, unwieldy penny-farthing, no less. If you don’t find this to be astonishing, you must never have attempted to teach a child to ride a bike. I have, and I can tell you it’s like trying to teach a horse to drive a car. But kids are the acme of flexibility. They are little learning machines. How Twain managed this feat in his relatively advanced years is a mystery—and then there’s the question of why he did it.

It’s a question that perplexed me in the days before I clambered onto the seat of a bike this past July, and began the arduous task of riding the two thousand or so miles from the headwaters of the Mississippi River, at Lake Itasca, Minnesota, down to New Orleans, following a trail cut by Twain himself on the riverboat he piloted more than a hundred fifty years ago. Along the way I documented the trip—dubbed the BikeTwain Project—in videos, tweets, and blog posts, using only power generated from the sun and a modicum of technological equipment.

I don’t suppose Mark Twain was coldly calculating enough to take on bicycling merely to have something to write about (though he did record his trials in the essay “Taming the Bicycle”), and my adventure too was about more than gathering material for a travelogue. As a cycling commuter, part of my plan was to exercise my wheels in the name of swapping cars for bikes. Twain himself was an early advocate for bicycle transport; for example, he’s quoted in an 1895 edition of Portland’s Oregonian suggesting the city macadamize its streets, purchase bicycles, and rent them out to citizens.

Or perhaps it was all for the tale. The man was an inveterate adventurer—not of the running-of-the-bulls-at-Pamplona variety, but he undoubtedly sought after stories. Aside from his steamboat days, Twain mined silver and gold, traveled the world and worked the lecture circuit, befriended wealthy industrialists and brilliant scientists, and ran a publishing house. Not everything ended well, but Twain was never at a loss for a tale. Many of his greatest stories spring directly from a wild adventure, including The Innocents Abroad (1869), Roughing It (1872), and Life on the Mississippi, published in 1883 with more than three hundred illustrations, which guided me on my trip.

Twain isn’t generally thought of primarily as an adventure writer, at least not against the background of swaggering thrill seekers who populated much of turn-of-the-century literature (think Jack London, Robert Louis Stevenson, Jules Verne, and their ilk), and he might be regarded as the first of a breed if his stories weren’t also so relentlessly ridiculous. From the tales of George Orwell and Ernest Hemingway, right up to Jon Krakauer and Sebastian Junger, literature is filled with thrilling, real-life journeys into darkness and back again, but the humor Twain brought to his exploits is what inspired my humble project.

It would be pretty presumptuous to label myself a modern Twain, but it’s not so gauche if you envision him as I did on my weeks riding the Mississippi: Twain running along beside me with his hand on the seat, letting go only when he felt I’d found my equilibrium. From Twain I hoped to find the wherewithal to face a sea of self-inflicted troubles—exposure to weather, worn-out gear, fatigue—in the interest of finding a story worth telling and transmitting it as sustainably as possible.

I departed Bemidji, Minnesota, and during the twenty-nine days that followed I pedaled through crashing storms, scorching sun, over brutal hills, and into insect-infested valleys. I suffered a succession of flat tires, the loss of a small fortune in damaged equipment, and frankly more dead animals than one man should have to smell in a lifetime. But I also met dozens of fascinating people, was treated with surprising hospitality, and listened to a virtual anthology of great stories. In short, it was an odyssey, as I’d hoped, reminiscent of the kind of journey made by Twain himself.

As a steamboat pilot he would have been in close contact with all sorts of people, from wealthy first-class passengers to humble deckhands. My own path exposed me to similar strata. It’s as though I’d found the pages of the American book peeled apart to reveal another story in between. I found the carless world of rural, suburban, and small-town America populated more by folks on the edges of affluent (car-equipped) society, encountering my fair share of disenfranchised citizens taking to roadways by foot or on bike.

I also discovered a side of carlessness at large that felt more optimistic. There’s a small cadre of people who, like myself, have slipped in between the pages in search of a better book—a tale of perseverance against tangible adversity. I met two trios of cyclists making the long haul to Oregon. I met a man who takes a long-distance trip every year, often on a bicycle, but also via Rollerblades, on foot, and even by swimming. And I caught up with a parcel of riders out for a day trip who, envious of my journey, spoke longingly of the day they might do the same.

As I encountered the varying paces of American bike communities and reflected upon the ways transportation affects our culture, I was reminded of Twain’s dismay at the loss of the steamboat under the wheels of the train. I won’t suggest that bicycles are going to overtake cars, but they are out there in growing numbers, which is far more than Twain could say about his beloved paddle wheeler. With Twain’s river by my side, another line from the bike tamer rang truer than ever: “Get a bicycle. You will not regret it, if you live.”

Fletcher Moore is a computer programmer and writer in Atlanta.