This is an extended version of the article that appears in the print edition of Poets & Writers Magazine.

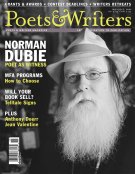

The author of 21 books, poet Norman Dubie was born in 1945 in Barre, Vermont, and was writing poetry by age 11. He has always written, as he puts it, “out of the spirits of winter.” Indeed he completed his first book, Alehouse Sonnets, a volume of poems written to the 19th-century English essayist William Hazlitt, during a blizzard while a graduate student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. The manuscript was chosen as a runner-up for the International Poetry Forum Prize, by a jury that included Richard Howard, and was published by the University of Pittsburgh Press in 1971.

It was Howard who recommended Dubie to launch the MFA program at Arizona State University in Tempe, where Dubie moved in 1975 and has lived for the past 30 years. Summers in the desert, which can bring temperatures of 120 degrees, have become his winters, when he “goes recluse” and writes.

Throughout his career, Dubie has become known for his persona poems—in his earlier work, for his dramatic monologues in the voices of historical figures, such as Queen Elizabeth I, Czar Nicholas of Russia, and Virginia Woolf. After the publication of The Everlastings (Doubleday, 1980), he decided to shift his chosen form from long, narrative poems to short lyrics: The Springhouse (1986), Groom Falconer (1989), and Radio Sky (1991), all published by Norton, followed. In 1992 he published The Clouds of Magellan (Recursos Press), a book of aphorisms written in the tradition of those in Wallace Stevens’s Opus Posthumous. He has also published his poetry in fine press editions and extensively in magazines, and his work has been translated into 30 languages.

After 20 years of a prolific career—publishing a book every other year or so—Dubie decided in the early ’90s to embark on a silence. The break coincided with his turning toward what has become the central focus of his life—the practice of Tibetan Buddhism.

I went to interview Dubie during monsoon season in Arizona, a time of vast storms that sweep over the desert, kicking up walls of sand. The occasion marked a return for me—I had studied with Dubie at ASU in the early 1990s. And it also marked Dubie’s return, it seems, to the publishing life.

His silence, which lasted the greater part of a decade, was broken in 2001 with the publication of his collected and new poems, The Mercy Seat, by Copper Canyon Press. The book received the annual PEN USA Prize for Best Book of Poetry. In November 2002 he published in the online journal Blackbird the first section of The Spirit Tablets at Goa Lake, a three-part, futuristic epic poem inspired by Buddhist teachings. The second and third sections followed online in the spring and fall of 2003. The Spirit Tablets is 400 pages in length and was composed entirely through dictation; in the evenings Dubie spoke the poem, while poet Laura Johnson typed it, inserting line breaks along the way. In October Copper Canyon released his latest volume, Ordinary Mornings of a Coliseum. Dubie is already at work on another.

We talked in his apartment over a couple of late afternoons—Dubie rises at about noon. He sits in meditation upon rising, at sunset, at sunrise, and sometimes in between. His apartment, once an average two-bedroom, is so ornamented with Buddhist objects, arranged together like small shrines, that the rooms seem circular, the edges rounded off. It’s an incredible place. After a warm greeting, he insisted on feeding me first—a hot pastrami sandwich with cottage cheese on the side—and then we began.

What interests you about the desert?

For a while I was very spooked by the desert. There’s a lot of sentient life here that we don’t necessarily see but feel. At this late date, I feel an actual connection with the old platform cultures that lived by the Salt River, where I live now. This area was very powerful to the people who were living here in, say, 1200. As a matter of fact, the Akimel O’odham used to say that there was such a history to this valley, so many illumined dead, that just to walk here on the land was to dream.

Before you settled in Arizona, you were at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Did you feel that anyone there was a particular mentor to you?

George Starbuck and Marvin Bell. Marvin was also a dear friend. George was a wonderful teacher to me. In fact, when he was leaving Iowa City to go, I believe, to Boston University, he took me to Donnelly’s. It was a place where Dylan Thomas fell from a bar stool to the floor and that sort of thing. George sat me down and said, “You know, I have this sense—I don’t know if it was a daydream or maybe I was just napping—that you are going to write a huge, long poem, 400 pages or something like that.” Until recently I thought that was complete insanity, but he charged me with this poem. And the responsibility to do it eventually hung over my head. I had no idea what shape it would take ultimately. It’s in the tradition of science fiction. So George was not only an important teacher to me when I was working on my first book, but his spirit urged me to write The Spirit Tablets at Goa Lake.

Marvin Bell was a wonderful teacher to me and David St. John, Michael Burkhard, Michael Ryan, and Larry Levis. We would go off to coffee shops and bars and talk about poetry. You learn a great deal in bars, and in Iowa City you learned a great deal from your peers as much as from faculty. Marvin was a very intriguing reader of poetry and in effect he was beside us, reading with us, and writing with us as well. There was no major anxiety about his being the teacher and my being the student. He would leave us very relaxed. It was clear in our minds that he wanted us to go through some sort of exciting progress of discovery and that we were better off writing something really bad than something boring.

Did you know John Berryman?

I met Berryman not that long before his death. He was in Des Moines, at Drake. I think he was getting an honorary PhD. It was extraordinary to sit there with not that large an audience and have him read from the 77 Dream Songs and His Toy, His Dream, His Rest. He had incredible nervous energy. He had a nervous syntax, which is remarkable and makes the Dream Songs so unique.

[After the reading] I walked into the back of the dean’s house looking for the john and saw in the poor light of the kitchen, a man standing in front of the sink getting water. Water seemed like the next thing I would need. I went in to get it, and there was Berryman. He was such a sad figure there in that poor light. He seemed both very empty and very scared. We spoke a little bit—he was joking with me and being fatherly, talking about Don Justice, as I recall. We both went forward to the piano room, and there Maura Stanton was. He instantly, truly lighted up when he saw Maura, and walked up to her and began asking her questions like, “Do you think wickedness is soluble in art, my dear?”

You’ve said that your father was a radical minister.

Yes, he was. He was opposing the war in Vietnam from the pulpit in Andover, Massachusetts, with Raytheon executives down there in the pews. He was for prison reform, and there were always pantries in the back of the house with food for people who were hungry. My mother was a registered nurse. I got the weirdest introduction to writing from them—my mother, because she would come home from the hospital with the most grisly and grim, detailed stories about people dying, children dying. And she had to unload it, so she’d unload it at the supper table. We all had a love of detail, so we understood. She was as good a nurse as you could hope to have ever had. Very compassionate. And she had to clear a lot of this stuff, I suspect. I really learned not to blink, not to look away, from some of those things in life that are ugly and involve suffering.

And I watched someone who, every Saturday night, on a weekly basis, would steal up to his study, turn on big band music, and write a sermon—twelve, fifteen pages or something—which, with two to three hours’ sleep, he would then share with us all the next morning.

Because my father would sometimes be moved by things and would get weepy in the pulpit—and, of course, that was the most embarrassing damn thing that could happen to me as a little boy, with all my little-boyish friends around me—I was always completely on edge and alert when my father was preaching. I never knew when he was going to start crying in front of everyone. He was a brilliant writer. He made the strangest metaphors. He knew his Greek tropes. Some of his sermons are still memorable for me today. I know I picked up some of his phrasing Sunday after Sunday, listening. It was never boring. Like I said, I felt vulnerable during that, but connecting writing with that strange, adolescent anxiety about showing emotion helped me to defeat those instincts in myself to be shy and reserved, at least in terms of the writing. I think I could find a bold voice in my poems simply because of his example.