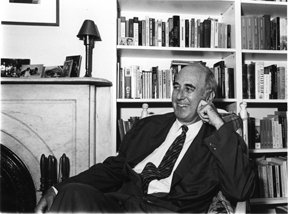

Phillip Lopate is considered by many to be one of the most important essayists of our time, a writer and editor at the fulcrum of memoir's resurgence who has contributed significantly to discourse on creative nonfiction. The anthology Lopate edited in 1994, The Art of the Personal Essay (Doubleday), helped contextualize the genre as part of a global tradition dating back to the classical period.

Born in Brooklyn in 1943, Lopate studied at Columbia University and received his doctorate from Union Graduate School. His first book of creative nonfiction, the memoir Being With Children (Doubleday, 1975), was an account of his experiences working in public schools, where he taught poetry for twelve years. Lopate has also published two poetry collections, The Eyes Don’t Always Want to Stay Open (Sun Press, 1972) and The Daily Round (Sun Press, 1976), and two novels, Confessions of Summer (Doubleday, 1979) and The Rug Merchant (Viking, 1987). A pair of novellas titled Two Marriages is forthcoming from Other Press in September.

But it is for his personal essays, collected in Bachelorhood: Tales of the Metropolis (Little, Brown, 1981), Against Joie de Vivre (Simon & Schuster, 1989), Portrait of My Body (Anchor, 1996), and Getting Personal: Selected Writings (Basic Books, 2003), that Lopate is best known. He has also published a meditative chronicle of a walk around New York City titled Waterfront: A Journey Around Manhattan (Crown, 2004) and is currently working on a book about Susan Sontag.

The recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and two grants from the National Endowment of the Arts, Lopate currently holds the Adams Chair at Hofstra University, where he is a professor of English, and teaches in the Bennington College MFA program.

Lopate spoke with Poets & Writers Magazine about the controversies surrounding creative nonfiction, his own essay-writing process, and the ultimate quality he looks for in nonfiction—an interesting mind at work on the page.

Poets & Writers Magazine: In a previous interview, you said you prefer the term “literary nonfiction” to creative nonfiction.

Phillip Lopate: Yes. “Creative nonfiction” seems slightly bogus. It’s like patting yourself on the back and saying, “My nonfiction is creative.” Let the reader be the judge of that.

P&W: What about applying that to the term “literary”?

PL: There is a bit of self-congratulations in “literary nonfiction.” One reason I prefer it is because it embeds the work in a tradition and a lineage. Instead of implying this is something new, it says this type of writing has been around for a long, long time. In English literature, there is the great tradition of the English essay, with Samuel Johnson, Hazlitt and Lamb, Robert Louis Stevenson and de Quincey, Matthew Arnold, McCauley, Carlisle, Beerbohm, and on into the twentieth century, with Virginia Woolf and George Orwell. By saying you write literary nonfiction, you’re saying that you’re part of that grand parade.

Creative nonfiction is somewhat distortedly being characterized as nonfiction that reads like fiction. Why can’t nonfiction be nonfiction? Why does it have to tart itself up and be something else? I make no apologies for the essay form, for the memoir form, or for any kind of literary nonfiction. These are genres that have been around for a long time, and we don’t have to apologize for them, or act like they’re new fads when they’re not. A colleague pointed out that James Frey, in his defense, said memoir is a new genre. He said there aren’t as many rules as there were when Hemingway and Fitzgerald were writing fiction. This is total nonsense because, in fact, Hemingway and Fitzgerald both wrote nonfiction as well. Frey showed his ignorance. Nonfiction is a very old genre. Go back to The Confessions of St. Augustine. For so long, individuals have attempted to understand how one lives and what one is to make of one’s life.

P&W: Do you have any rules or guidelines for writing nonfiction? Are they different than Lee Gutkind’s?

PL: Gutkind emphasizes using a lot of scenes, dialogue, and cinematic and sensory detail to increase vividness of writing. That’s fine, but not every piece of nonfiction has to have scenes or dialogue.

There’s a kind of bestseller that’s being written now, true crime nonfiction, which is essentially told through scenes. Perhaps this goes back to Capote’s In Cold Blood, or Mailer’s Executioner’s Song, but the idea is to write a kind of narrative that makes you feel like you’re watching television, so it’s very close to a screen play. That’s okay, but I don’t see any reason to encourage graduate MFA nonfiction students all to write that way.

I am more interested in the display of consciousness on the page. The reason I read nonfiction is to follow an interesting mind. I’ll read an essayist, like E. B. White, who may write about the death of a pig one time, and racial segregation another time. Virginia Woolf may write about going on a walk to find a pencil, which seems like a very trivial subject, or about World War I, or a woman’s need for a room of her own. She has such a fascinating mind that I’m going to follow her, whatever she wants to write about. One of the ploys of the great personal essayists is to take a seemingly trivial or everyday subject and then bring interest to it.

I have no desire to pick a fight with Gutkind. I’m arguing more for reflective nonfiction where thinking and the play of consciousness is the main actor.

There is a lot of great fiction that is largely reflective. Proust, Robert Musil, Hermann Broch, Sebald, Conrad, Samuel Beckett, on to the post-modernist people like David Foster Wallace and Nicholson Baker. It’s not true that fiction is always showing and not telling. That’s a distortion, a very narrow way of looking at fiction.

One objection you could make to my prescription is that it’s rather snobbish. I’m interested in intelligence and interesting minds. You could finesse a certain amount of technique, scenes, and dialogue, but it’s hard to finesse having or not having an interesting mind. I try to read writers who are better than I am, or who have deeper minds than I do because I need to learn.

P&W: At NonfictioNOW [a biennial conference sponsored by the University of Iowa Nonfiction Writing Program], there was an editor from Random House who made the comment that you don’t want to put “memoir” on a jacket cover these days, that it’s not marketable. Do you think of the memoir as being sullied?

PL: This is part of the endless re-branding that goes on in American consumer culture. I don’t take it seriously.

A friend of mine, Lynn Fried, wrote a collection of essays, and her editor didn’t want her to call it essays. It was called Reading, Writing and Leaving Home, but obviously it was a collection of essays. Editors find it hard to sell collections of essays. It’s easier to sell a book that’s about one single topic, that has a through-line.

This doesn’t mean that there’s anything wrong with collections of essays. Some of it depends on the status of the essayist. Joan Didion was able to get her personal essays published without having any coherent through-line because people wanted to read her. So, if another Joan Didion comes along, we’ll want to read him or her, regardless of what you call it.

P&W: What is the difference between personal essay and memoir?

PL: The memoir requires other people. The personal essay can avail itself of other people, but it can also be a reflection on a subject where other people are not necessarily that important. For instance, William Hazlitt has the essay “On Going a Journey” that talks about how he likes to walk around by himself. That isn’t one that particularly avails itself of another character. It is about solitude, which is a kind of classic subject of the personal essay.

The Sunday sermon, or the sermon in the synagogue, is also a kind of essay, a meditation. In previous centuries, writers like Laurence Sterne and Jonathan Swift wrote sermons, and it was clear that there was a connection between the essay and the sermon. Basically, we’re talking about a meditation, reflection, or reverie. The literature of the sermon is quite substantial and important, and can be looked at as a species of belles-lettres.

A lot of literary nonfiction that I’m interested in, such as the personal essay, aims, in the end, for wisdom. In a personal essay, you don’t want to get too moralistic or preachy, but you are going after wisdom.

P&W: In her essay “Book of Days,” Emily Fox Gordon describes memoir and personal essay, and quotes you as saying the essayistic process is one of “‘thinking against oneself.’” How do you think against yourself? Is it possible in memoir?

PL: Yes, many of the best memoirs do. How? You play back what you just wrote, and say, “Do I really think that? What is the argument against that?” When you’re writing an essay, you as the essayist are both moving forward and circling back to what you said and arguing with yourself, or at least asking yourself if this is what you really think. That’s part of the scrupulousness of this kind of writing. It’s not, is this what others think I should think? but, is this what I actually think?

P&W: In The Art of the Personal Essay, you say you want to tell students, “figure out something on your own, some question to which you don’t already have the answer when you start.” How do students “figure out something” on their own?

PL: You have to try to liberate them from the conformities and received truths of society, many of which are highly debatable. It’s not too different from the aim of cultural criticism or critical theory, which tries teach students to look at the world around them in a more skeptical manner, to feel less lonely in their antisocial thoughts and their inability to “get with the program.”

One issue is the limits of our sympathy, and that we can’t always sympathize with people in need or in trouble. We wrestle with our solipsistic condition, and most people fall into a kind of self-absorption. We know that we should be open more to others, but we’re very self-pre-occupied. But, if we become friends with our minds, we will be less harsh on ourselves for not being perfect, for not being saints. We’re not saints, for the most part.

One of the things that literature does—and here I’m not just talking about essays, but about Greek tragedy, Shakespeare, the great novels of the nineteenth century—is it allows us to be more understanding about human frailty, about error, tragic flaws, and therefore, makes us more forgiving, and more self-forgiving. That’s a kind of wisdom.

We have these impulses and unsatisfied desires, but the economy of life is set up so that you’re not going to sleep with everybody that you want to sleep with. You’re not going to get all the credit that you want to get, or all the goodies that you want to buy. You have these impulses, and this is what Freud meant when he talked about civilization and its discontents, that the world is constructed in such a way that we’re going to be frustrated to a great degree. Part of the way that human beings struggle with this is that they try to teach themselves a kind of resignation or stoicism, an acceptance of what they have. Literature enacts the sinful impulse, giving us an opportunity to try out these lives or these thoughts, and to release them as a kind of safety valve.

Instead of persuading everybody that they have to be good, and that they mustn’t think those bad thoughts, the personal essayist often expresses mischievous thoughts, and the reader connects with those thoughts. If the personal essayist only expresses pious thoughts, it’s probably going to put the reader to sleep. But, it’s in the entertaining of these mischievous thoughts and the fingering of doubts that we acknowledge the complexity of humanity and move closer to a realistic assessment of human character.

P&W: You said something earlier about consolation.

PL: Yes, consolation.

P&W: Would you talk about that?

PL: The “consolations of philosophy” is one of the themes of philosophy. In Greek and Roman times, the stoics were a philosophical school that offered consolation through stoicism. There were also the Epicureans, the Skeptics, and so on. Religion offers its own consolations, the idea of the life after death. I’m drawn toward a kind of consolation that is more realistic—the consolation of minimal consolation. Don’t promise me life after death. Don’t promise me redemption.

P&W: Because those are the big consolations.

PL: Right, I find it hard to believe in them. But, there is the consolation of, “Yeah, that’s the way it is,” which is what Chekhov said. He wanted to write the way things were, not the way things should be. He said, “You live badly, my friends.” He wanted to show people that they lived badly, and strangely enough, there’s a consolation in that.

P&W: In Richard Rodriguez’s address at NonfictioNOW, he quoted Emerson saying, “It takes a good reader to make a good book,” and followed that with the pronouncement that, “We are a group of writers in a world that doesn’t read.” What are your thoughts on literacy and readership?

PL: I agree with Emerson and with Richard Rodriguez. We need good readers.

There is certainly resistance at the undergraduate level to a lot of reading. One of the satisfying things about graduate literature and MFA programs is that those students want to read.

P&W: What is the relationship between reading and being a good writer?

PL: It’s an intimate one. I come from the old school, and I don’t understand writers who aren’t readers. Sophistication comes from reading. You develop worldliness on the page, which is one of the most important assets a literary nonfiction writer can have.