In April 2003, an agent sat down with me, pointed to my manuscript, and said the words I had been dreading: I think this should be a novel. I shuddered. I was no novelist. I was a minimalist, a votress of the goddess of gesture, a worshipper at the altar of the succinct. I was a short story writer.

This wasn’t the first time someone had tried to steer me away from short fiction. “Write a novel,” my friends of the longer form told me. “You can’t build a career on short fiction.” Alice Munro, I insisted. Mavis Gallant. Raymond Carver. Grace Paley. Vocational short story writers all. Besides, I had had my share of publications, and my stories were coalescing as a book—not just a short story collection but a linked short story collection, with shared characters, themes, and issues. Linked story collections, as we know, are all the rage. I ignored the advice and sent my manuscript to an agent recommended by one of my short story editors. Thus it was that I ended up in a Japanese restaurant, hearing the raw truth over (appropriately) sashimi.

The agent in question, Nat Sobel, is nothing if not gracious. He ordered a bottle of sake and filled my glass several times before delivering the news: My linked collection of stories was trans-genred. It had a novel inside, a novel just longing to get out. I stared glumly into my hijiki. Although every fiber of my being wanted to protest—Start over? You’ve got to be kidding!—at that moment, I suspected Sobel was right. Perhaps it was the timing. Perhaps it was his conviction. Perhaps it was the sake. I went home with a headache (definitely the sake) and spent the weekend moping.

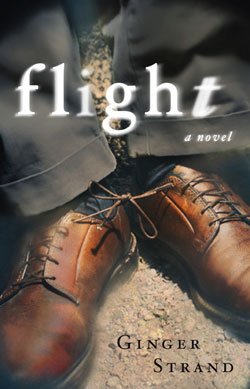

It was tempting to get a second opinion, but I have always believed in listening to sound advice, and, although I resisted it, Sobel’s advice felt right. On Monday, I got up, swallowed my pride, and sat down at my computer. And what happened then was astounding. Over the next four months, I wrote a novel—the one that somehow, amazingly, was waiting to emerge from my stories. Even more amazing was that when I sent it to Sobel, he was pleased. He sold it to Simon & Schuster, and this month, my novel, Flight, will be in bookstores.

I still love short stories, and I still write them. I would never suggest that short fiction be viewed as a springboard to something longer. But if, like me, you have a group of short stories that are trying to become a novel, it may help you to hear some of the things I learned as I lost my fear of Flight—and became a novelist.

WHERE ARE YOU GOING, WHERE HAVE YOU BEEN?

In thinking about the “novelness” of my collection, the first thing I did was look at where it ended. I didn’t look to the story that appeared last in the collection, which skipped around in both time and point of view. Instead, I looked to the story that seemed farthest along chronologically in the lives of the characters. Even if your stories aren’t linked, and the characters vary from story to story, the one that is set last in terms of time is the place to look for the ending of your potential novel. What problems are resolved in that story? What resolutions are reached? I looked hard at that story to understand why and how I felt comfortable in leaving my characters where I did.

All of this is just a way of talking about finding your novel’s thematic arc—the development of the ideas or issues that are at stake in your work. You may not find clues to your novel’s thematic arc in the story that takes place last in terms of time; instead, you may discover them in a story that explains or resolves something for your characters. Another way of approaching this task might be to ask yourself: Are some of the stories working toward another of them? Looking at my “last” story, I could see that it drew together many of the themes and ideas addressed by other stories. It helped me to answer that always perplexing question for writers: “What am I really getting at here?” Not that we ever know completely. We’re always stumbling forward in a darkened room. But having a general sense of the room’s contours helps us grope our way around it.

THE 80-YARD RUN

You might think that what follows would be to place the stories in chronological order, throw in some deft transitions, change the story titles to chapter numbers, and call up your agent saying, “Voila! A novel is born!” Right. Maybe for some people writing works that way. For me, it turned out to be far more complicated. Because once I understood the thematic arc, I saw that many of the stories I had labored over for so long were, in the novel context, background. They served more as character development—strong character development, but character development nonetheless. My novel needed some action. It was lacking what playwrights call the through-line—the plot that would keep readers on the edge of their seats, wondering what would come next.

Everyone loves the maxim—ascribed to T.S. Eliot—that bad writers borrow but good ones steal. Since I am a timid and inept thief, I stole from myself. I filched my novel’s plot from the last story. Not only was that story a culmination of my themes, but its story line could be opened up enough to make room for the detail and characters contained in the previous stories.

This almost makes it sound as though novel writing were something akin to building model airplanes—insert tab A into slot B. It’s not, of course. And the only plot that will sweep your reader away with it is one you are caught up in yourself. I certainly was. I did the thinking and organizing the way I always do—on the subway and in the shower. (Believe me, I was very clean and well traveled by the end of this book.) But when I sat down at my keyboard, I found myself surrendering to the breathless forward movement that distinguishes novels. What’s she going to do now? Will his secret be revealed? Who could be at the door?

After years of writing short fiction, losing myself in a novel plot felt like climbing onto the roller coaster after countless perfect circles on the Ferris wheel. I gave in to the thrill of the ride. In fact, I had so much fun plotting, I found myself bringing in police officers and a car chase at the end. Okay, not really a car chase. More like a minor moving violation. But hey, it was action! Suspense! Forward movement!